These penultimate annotations are for the final chapter of the book Impossible Histories (there’s a postlude), which you can acquire just about anywhere, including here or your local library. No pressure on that acquisition, but these notes might make more sense with the book in hand.

p. 368

•Global Thermonuclear War: Obviously this is a nod to the movie War Games, because we cannot escape from ourselves.

•epigraph: The epigraph was to be:

Sex can be compared to atomic energy. It is a powerful force. Used wisely, it can warm our lives and enrich a meaningful relationship. Used carelessly or wantonly, it can cause an emotional explosion that may blow up our chances for happiness. Most of us believe that sexual as wall as atomic energy should be used for constructive purposes.

§The Seventeen Guide to Knowing Yourself (1967).

The book is by Daniel Sugarman and Rolaine Hochstein, but I was just going to leave them out. It’s a great quote, but I will sacrifice two writers at the alter of keeping an epigraph’s citation attractively short.

p. 369

•a veil of absolute secrecy:

This veil was at the time itself is unprecedented! You’ll notice that before nuclear weapons, governments didn’t have a lot of secret technologies. It wasn’t until 1911 that the US even had a law against “the disclosure of national defense secrets” and then these secrets were mainly things like the deployment of forces, or layouts of military installations. Even when a government did have a secret weapon, such as 1918’s top-secret British M-Device—an exploding shell that delivered poison gas (diphenylaminechloroarsine)—that secrecy scarcely covered an entire field of science. The British used poison gas to kill rabbits, M-Device or no. Poison gas wasn’t secret! But the Bomb was.

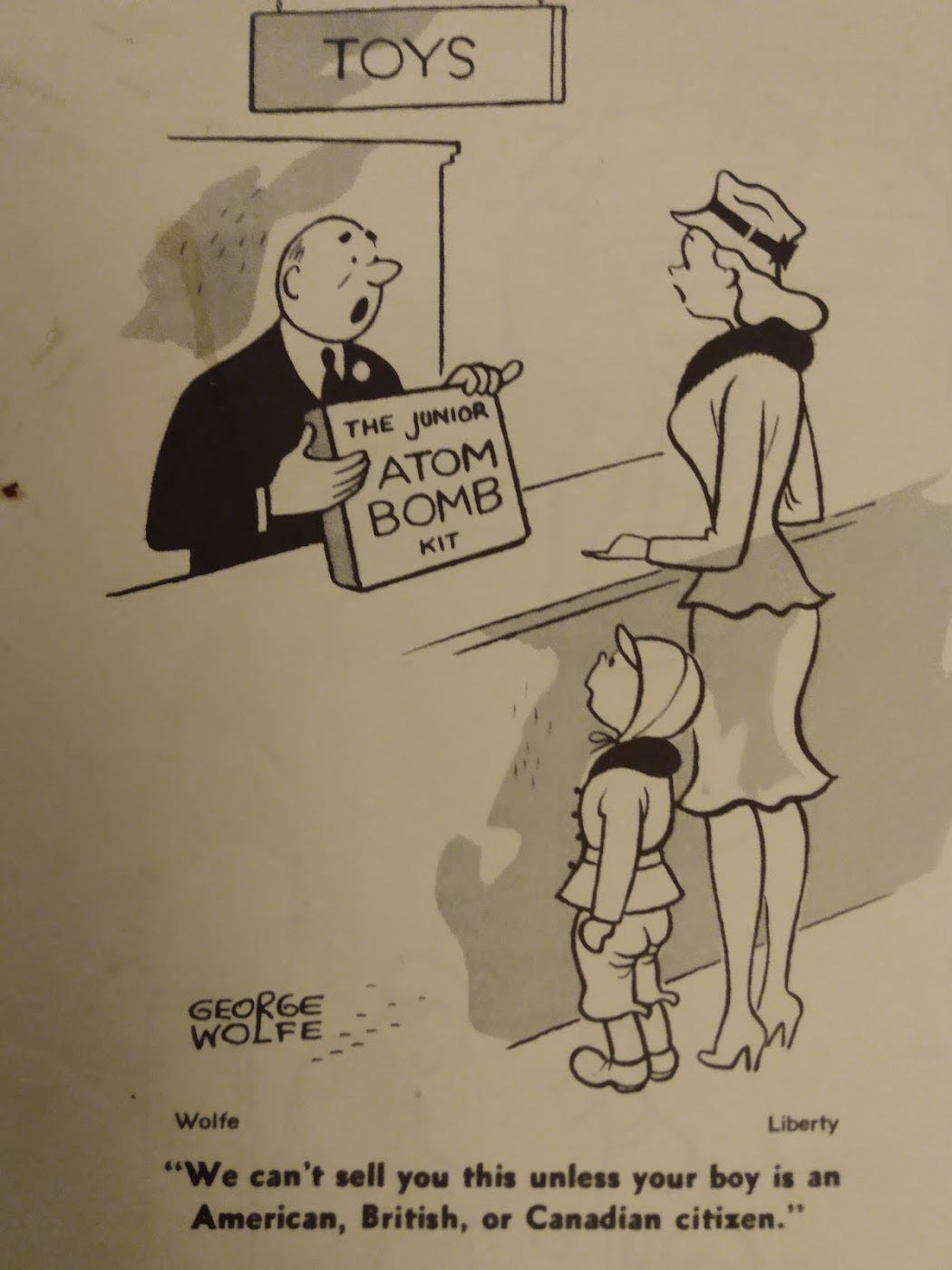

Nuclear science in its infancy (i.e. pre-War) had been a model of international cooperation: Lise Meitner, an Austrian working in Sweden, and Otto Frisch, an Austrian working in Denmark, crunched out a theoretical framework to explain the experiments of Otto Hahn (German), whose own work built upon the recent discoveries of Enrico Fermi (Italian), Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie (French), and James Chadwick (British). Only the conquests of Nazi Germany put an end to the scientists’ cosmopolitan spirit. (Incidentally, everyone in this paragraph except the two Austrians would go on to win Nobel prizes.) Fermi, Frisch, and Chadwick would later work in America developing the atomic bomb, but by that point there would be no openness. By that point the British, the Germans, the Soviets, the Japanese, and the Americans would all have rival and mostly independent nuclear programs (the exceptions to complete independence would be a sometimes grudging cooperation between the British, the Americans, and the Canadians (as per Wolfe, above), and a propensity of the Soviets’ to spy on everyone). The potential for fission to create an atomic weapon was therefore developed behind closed doors. No civilian organizations were even able to discuss whether development was a good idea. No plebiscite could be taken on early nuclear policy because no one knew enough to vote on. This widespread ignorance applied to the very governments that were developing atomic weapons: One reason the US pushed so hard to develop the A-bomb was a fear that the Germans might be on the cusp of developing it first; no one in American knew that the underfunded German program was nowhere near a breakthrough, Hitler having put all his money on a different secret weapon (the V-2 rocket).

p. 370

•two billion dollars: “And back then that was a lot of money.”

•Notorious, which started preproduction in 1944: But was the MacGuffin uranium in preproduction? According to Ken Mogg, the MacGuffin ”had started as a secret Nazi army being formed in Brazil, became ‘chemicals and mechanisms’ for building a ‘new German weapon’” and only later settled on uranium. Is it possible the uranium angle was added late in the game? [Ken Mogg, The Alfred Hitchcock Story (Titan, 2008) p. 98.]

p. 371

•Only two people: In 1965, postmodern novelist Donald Barthelme published a story about one crewman trying to persuade the other crewman to turn his key (read it here); but that’s only a story, and Barthelme, as a postmodernist, is not to be trusted.

p. 375

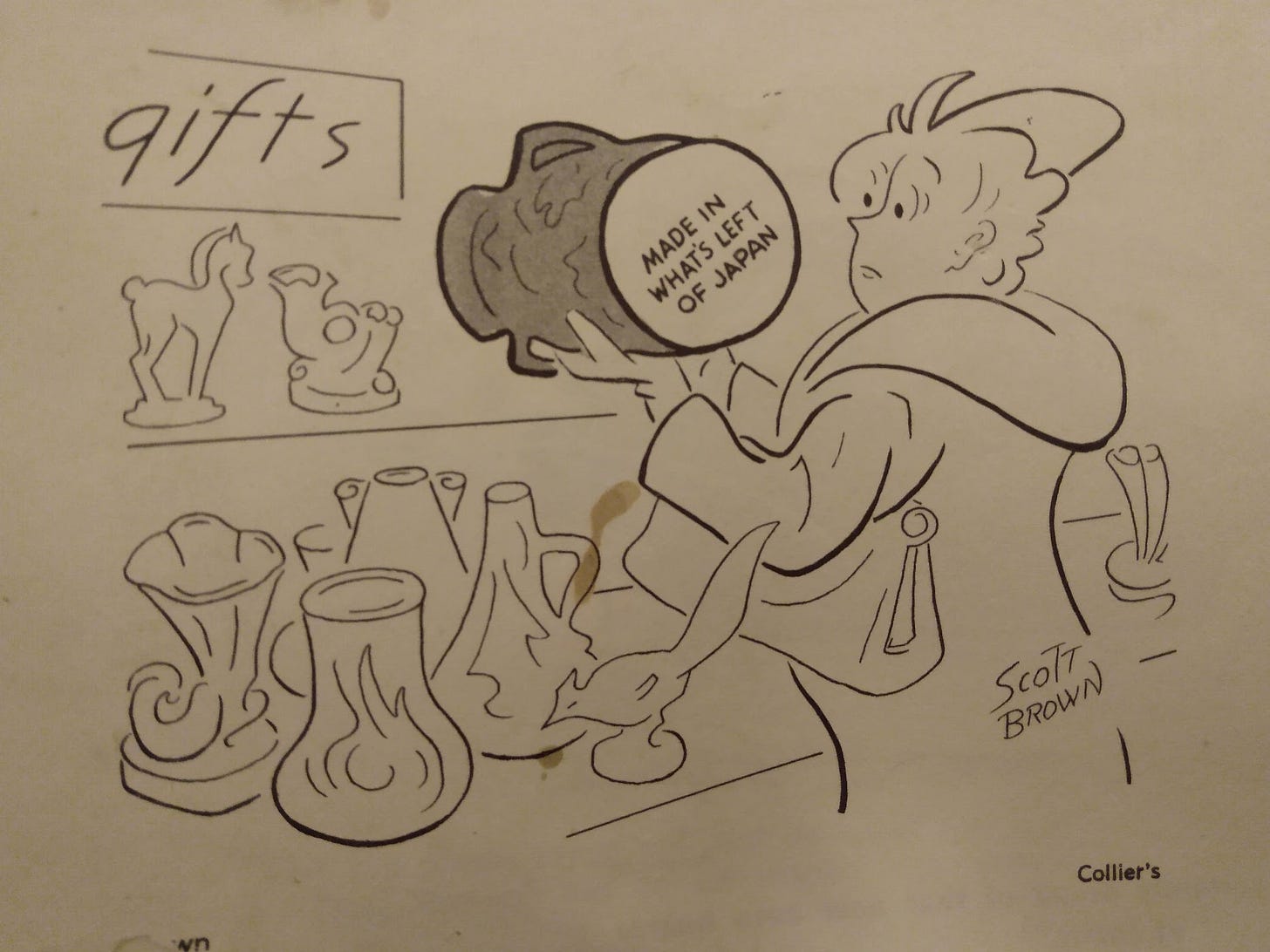

•an incentive to overstate the power of atomic weapons: This postwar cartoon is indicative of the perception that the two Bombs had absolutely leveled Japan.

p. 377

•any nuclear explosion in warfare: Just because they have not exploded does not mean nuclear weapons have not been used. The book’s next paragraph deals with deterrence, but examples could be multiplied (or maybe they could not; hard to tell with deterrence).

Eisenhower always credited the threat of a nuclear strike—he didn’t actually come out and threaten it, as back then presidents were diplomatic and subtle, but the threat existed nevertheless—with ending the Korean War. Was Ike right? It’s also possible that Mao was not actually that eager to keep throwing his soldiers into Korea, but felt pressured into continuing because of pressure from the Soviet Union, his ally. Once Stalin died, and the pressure lifted, Mao quickly negotiated a peace.

A few years later, in 1955 and 1958, China and Taiwan (and therefore China and the US) clashed over possession of two small islands, Quemoy & Mastsu; once again, the implicit threat of the American Bomb kept the conflict from escalating beyond saber-rattling, and China gave in. By 1964, China had the Bomb, too, and nuclear threats became more dangerous. Nevertheless, despite decades of tensions, Taiwan and China have not gone to war.

How often has this happened? Did NATO back down in its objections to the 2008 Russian invasion of Georgia because the Russians chose to bring out nuclear-tipped Iskander missiles? Actually, Iskander missiles can hold both nuclear or conventional warheads, so there may not have been any nuclear missiles on the front lines; but there might have been. None ever launched, though. NATO refused to intervene, and the Russians still occupy parts of Georgia. It may have been nothing, but it may have been the nukes.

p. 378

•Cuban Missile Crisis: The CMC had such an outsized impact on American culture…This is a line from Ralph Pape’s 1979 play, Say Goodnight, Gracie:

When he looked into the camera and told the nation that there were missiles in Cuba, he was incredibly sexy, I thought.

And surely this is part of it…not just the threat of nuclear annihilation, but the coupling of that threat with the Kennedy Mystique (TM). Here, in toto, is Lorine Niedecker’s 1967 poem “J. F. Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs”:

To stand up—

black marked tulip

not snapped by the storm‘I’ve been duped by the experts’

—and walk

the South Lawn

[Pape, Say Goodnight, Gracie (Doubleday, 1979) p. 28; Niedecker, From This Condensery (Jargon Society / Inland Book Co., 1985) p177.]

p. 379

•epigraph: And here we would have had:

God’s plan made a hopeful beginning But man spoiled his chances by sinning. We trust that the story Will end in God’s glory; But, at present, the other side’s winning. §Oliver Wendell Holmes, attr.

p. 380

•Brian Martin: Is Brian Martin a good source? Maybe he has a reputation as a wacko, especially now, when writing about COVID vaccinations make it easy to be a wacko. I finished this chapter before the pandemic, in a lull between when Martin was famous for being controversial/wrong about AIDS and when Martin was famous for being controversial/wrong about COVID. I didn’t know much about him when I read his estimate. Perhaps I would have looked for a different source if I’d gone back and checked him out again later.

But perhaps not. Martin writes soberly about the things he’s being controversial about. I like gadflies, even gadflies I disagree with. Martin pretty consistently says that he has no strong opinions about vaccines and is merely interested in their social science aspect, and it’s not like vaccine orthodoxy and heterodoxy is not a fertile field for a social scientist. I mean, Martin could hardly be more one-sided than Ron Rosenbaum.

Maybe if I’d been soberer I would have cited this guy instead.

•a freak rainstorm: As Alan Moore once wrote, “It’s like old naval battles. So much depends on a quirk of the wind.” [Watchmen #3 (Nov. 1986)]

p. 381

•the assumption this chapter started with: This assumption is so prevalent in nuclear discourse…I’ll limit myself to just one example, when Martin Amis in 1986 said Ronald Reagan “like his opposite number…is the keeper of the planet, of all life, of the past and of the future.” [Amis, The Moronic Inferno (Penguin, 1986) p. 96.]

p. 382

•a nuclear war that does not escalate: Sometime in the ‘90s I read an interview with Eve Ensler in which she said she literally could not imagine a limited nuclear war. If anyone can find the source of that interview, please let me know; I want to make fun of it.