These are annotations for the twelfth chapter of the book Impossible Histories. I’m not saying you need to keep a copy of IH open next to you as you read, but it might make some things clearer?

p. 227

•epigraph: The epigraph was to be:

I think ill of the world, (continued Byron,) but I do not, as some cynics assert, believe it to be composed of knaves and fools. No, I consider that it is, for the most part, peopled by those who have not talents sufficient to be the first, and yet have one degree too much to be the second.

§Marguerite Blessington, Conversations of Lord Byron (1834).

•You can probably look at the moon: From The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon (ca. 1000):

‘Why so silent?’ said Her Majesty. ‘Say something. It is sad when you do not speak.’

‘I am gazing into the autumn moon,’ I replied.

‘Ah, yes,’ she remarked. ‘That is just what you should have said.’

[The Pillow Book (Columbia UP, 1991) p125]

•Nothing is valued unless it is rare: A counterpoint, from Sei Shonagon again: “Do people tire of the cherry trees because they blossom every spring?” [Ib. p. 64.]

p. 228

•technical mastery: I apologize for all the quotes but who can resist?

Parrhasius…entered into a pictorial contest with Zeuxis, who represented some grapes, painted so naturally that the birds flew towards the spot where the picture was exhibited. Parrhasius, on the other hand, exhibited a curtain, drawn with such singular truthfulness, that Zeuxis, elated with the judgment which had been passed upon his work by the birds, haughtily demanded that the curtain should be drawn aside to let the picture be seen. Upon finding his mistake, with a great degree of ingenuous candour he admitted that he had been surpassed, for that whereas he himself had only deceived the birds, Parrhasius had deceived him, an artist.

[Pliny, Natural History XXV.36.]

Three other good stories of artistic skill can be found here.

•the proof was in the pudding: A friend of mine always corrects this proverb to be: The proof of the pudding is in the eating; but I am unconvinced.

p. 229

•Audacity was the calling card of Modernism: Reducing Modernism to audacity is probably thoroughly irresponsible, but perhaps an example will make me look like less of a jerk.

Take, as our example, Max Ernst’s 1934 surreal novel Une Semaine de Bonte (A Week of Kindness). This book is (in case you didn’t know) a proto-graphic novel composed of wordless collages cobbled together from nineteenth-century engravings. Any given page (each page is one full page illustration) is fine but conventional. I mean it is conventional for a surreal picture. It is (to invert Dr. Frank N. Furter’s phrase) conventionally unconventional. A man with a lion head tickling the feet of a woman bound to a bed; a woman in Victorian garb and a dragon giving a back rub to a somersaulting gentleman; 1934 was brimming with this stuff.

But this is not an art book! It is a novel! It says so right on the title page there that this is a roman. And as a novel, the work is groundbreaking! Suddenly the small similarities from picture to picture of the kind you might find in any artist’s work are not merely small similarities—they are a plot! These are characters doing things. As the book becomes more and more abstract towards the end, this is merely the story, the same way that Dante’s experiences become more abstract as he moves further through the Divine Comedy.

All it took to transform a conventional humdrum collection of collages into a major work of art was the audacity to assert its novelhood.

•Moderninsm: Modernism is of course much bigger than art; Modernism was at heart a totalizing system that sought to control all aspects of our lives; it has died out almost everywhere except in our educational system.

I’ll only be gesturing towards one of the manifold aspects of Modernism if I point out that when Orwell claims that socialists, to make the world less “untidy,” seek “to reduce the world to something resembling a chessboard,” he is picking on not socialism (which of course he favors) but on Modernism (which he certainly doesn’t). The clearest example of this Modernist will-to-tidiness can be found, I think, in H.G. Wells’s utopian novel The World Set Free, in which humanity at long last has the wherewithal to “nail down Easter.” The idea that four or five clerics are inconvenienced every twenty years or so in calculating Easter is too much for Wells’s brave new world! “In these matters, as in so many matters [Wells is explicitly referring to Easter as well as other calendar ‘improvements’] , the new civilisation came as a simplification of ancient complications.”

If you’ve ever passed a housing complex where every building and every entrance looks identical, and have assumed that it was built this way to save money, remind yourself that the initial impetus was to make H.G. Wells (or people with similar brain problems) happy.

[Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (HB, n.d.) p. 179; Wells, The World Set Free (Dutton, 1914) p. 238; cf., o.c., James C. Scott, Seeing like a State (Yale UP, 1998).]

•the lambasting Modernists received was unprecedented: Before they hated Modernists, they hated proto-Modernists (so I guess all my claim of “unprecedented” was just me talking out of my hat). Édouard Manet’s 1963 Olympia, for example, had people in a tizzy. Georges Bataille, in his monograph Manet, collected some of the responses of the time, and they’re worth reading because they don’t even resemble art criticism so much as an attempt to be mean.

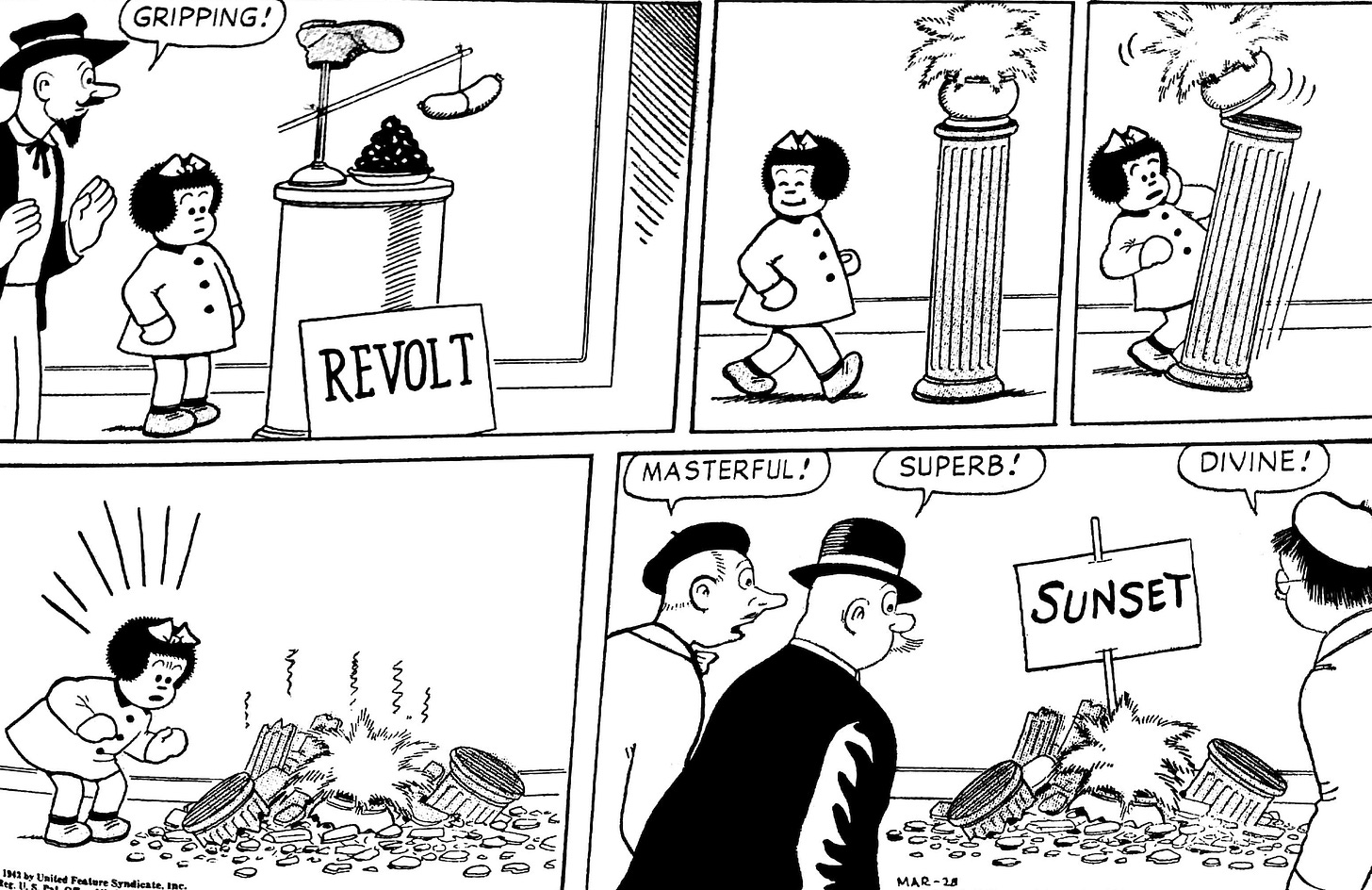

Such a picture might “stir up a revolt,” protested one Jean Ravenel in L'Epoque. And Jules Claretie in L'Artiste: “What on earth is this yellow-bellied odalisque, this wretched model picked up God knows where and pawned off as representing Olympia?” Ernest Chesneau, a critic who later stood up for Manet, wrote in Le Constitutionnel: “He manages to provoke a good deal of shameless snickering, which causes crowds to gather in front of this ludicrous creature he calls Olympia.” The daughter of Théophile Gautier wrote in L'Entr’acte: “The exhibition has its clown. Among all the artists is one who turns somersaults and sticks out his tongue.” “Never has there been a spectacle to equal it or anything quite so cynical as this Olympia, a kind of female gorilla,” exclaimed Amédée Cantaloube in Le Grand Journal. In Le Petit Journal Edmond About tried to sum things up: “Peace to Monsieur Manet! Public ridicule has done justice to his pictures.” The deepest shudder of all ran through Paul de Saint-Victor, a senior critic whose opinions carried weight: “The crowd gathers round Monsieur Manet’s highly spiced Olympia as it would round a body at the morgue. Art that has sunk so low is not worthy of our censure. ‘Speak not of them, only gaze and pass on,’ says Virgil to Dante as they make their way across one of the circles of hell.”

[Bataille, Manet (Skira, 1955) p. 61.]

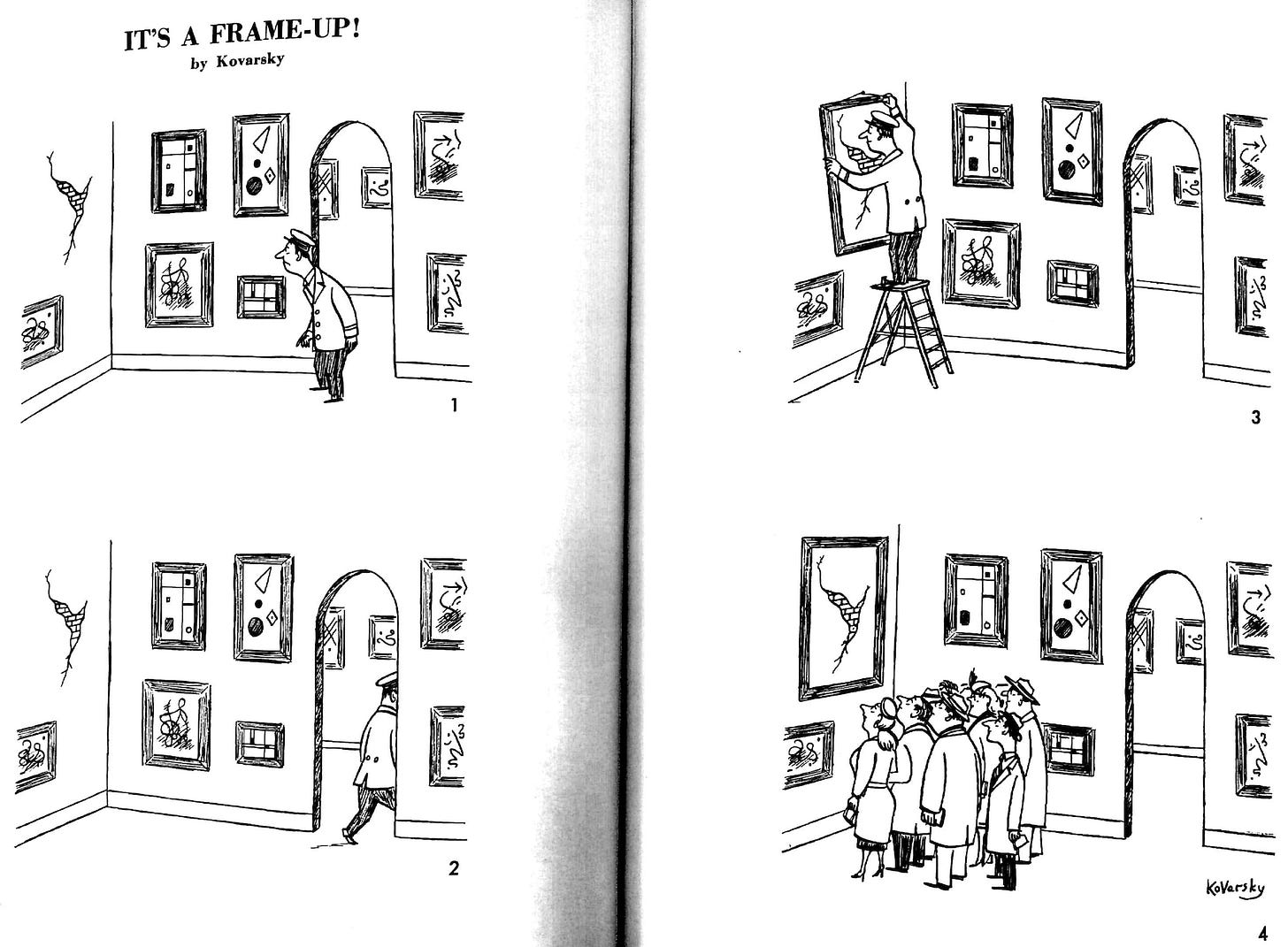

•See any issue of the New Yorker: The cartoons referenced (one of which, I guess, certainly did not appear in the New Yorker) appear below. I apologize for the bad scans; these books have tight bindings!

•etc.: Okay, just one more!

p. 231

•Lyrical Ballads: Despite being one of the seminal poetry volumes in the English canon, is Lyrical Ballads actually any good? If you’re interested in my review, the answer is sort of.

It does have “Rime of the Ancyent Marinere,” one of the all-time best poems; but it also has a lot of other poems as well. Certainly Wordsworth would become a great poet eventually, but was he a great poet in 1798? I mean, think of your favorite Wordsworth piece—the Lucy poems, the sonnets, The Prelude—well, you’re probably not going to find it in here. Instead, you’ll find a lot of broad melodrama, as weepy peasants whine out their sub-Les Mis sob stories. A little of this goes a long way. “Oh, look! Another poor person whose children are dying!”

“Goody Blake and Harry Gill” (while hardly not a melodrama about the sufferings of the poor lol) is fun, but still slight. “Anecdote for Fathers” is cute enough, but even slighter (and not helped by the portentous subtitle). “Expostulation and Reply” and “The Tables Turned” are fine, but so on-point. In fact, “fine” is a word I would use to describe most of the poems. Even when they’re ludicrously bathotic, they’re competent. But for Wordsworth, all you’re really left with is “Tintern Abbey,” which is not a lot.

Coleridge has a handful of poems beyond “Marinere.” Two are excerpts from his play Osorio, which are at times inexplicable on their own, and must have been especially inexplicable upon publication, with no critical apparatus. On the other hand “The Nightingale,” one of the better poems in the book, also has its inexplicable (“A most gentle maid” etc.) flights and interpolations, so maybe I shouldn’t blame Osorio. Maybe Coleridge poems (and this is certainly true even of his best ones) always have a kernel of mystery in them that baffles all reason, or at least all reasonable attempts to explain why certain passages were selected for inclusion. So: “Marinere,” “Tintern Abby,” maybe “The Nightingale,” a couple of jokey fun poems, and the rest no more than “fine.” That’s the wellspring of the English Romantic movement?

What can you do? I don’t make this stuff up.

p. 232

•epigraph: The epigraph here was to be:

He always accuses me of trying to look “cool”…I was like, “Everybody tries to look cool, I just happen to be successful…”

§Daniel Clowes, Eightball #17 (1996).

•one of those works that “starts something”: This chapter is really a chapter about the faddishness of literature, and so I wanted to digress here to talk about something I find interesting but which I couldn’t fit into the book, viz. the faddishness of novels’ titles.

Before the twentieth century novels used to have predictable, utilitarian titles, generally either the name of the setting (Wuthering Heights, Middlemarch, Washington Square) or the main character (Jane Eyre, Oliver Twist, Allan Quatermain), sometimes preceded by “the adventures/history of” (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia; Smollett’s 1769 twofer The History and Adventures of an Atom). Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is all three at once! The Scarlet Letter is indeed about a scarlet letter; The Red Badge of Courage is, with a certain degree of irony, about a red badge of courage. If you pick up A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, you’re not liable to complain you didn’t know what you were getting into.

Moby Dick; or, The Whale is just the name of a character, albeit one with no speaking lines; in case that wasn’t clear enough, the subtitle spells it out.

Jane Austen, who could name books after places (Northanger Abbey) or people (Emma), hit upon one of the more fanciful naming schemes of the nineteenth century with Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility. Although later, more lowbrow writers would copy this pattern, and Horatio Alger alone cranked out Fame and Fortune, Slow and Sure, Do and Dare, Strive and Succeed, Try and Trust, etc. (also Rough and Ready, although that is just the protagonist’s name; don’t blame me, his name is literally Rough and Ready*), Austen’s abstractions were the exception. For every Great Expectations there are a dozen like Ivanhoe, The Mayor of Casterbridge, or Typee (Typee is part of French Polynesia, where Melville had been marooned).

Earlier novels have the complicating factor of titles that are really long. The book we know and love as Robinson Crusoe was released as The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner…and then the title goes on for fifty plus more words, summarizing the plot of the book, and even spoiling the ending. This is nothing if not literal.

Then something changed after the first quarter of the twentieth century. Look at some of the key titles from America’s heavy hitters of the time, the Nobel Prize laureates Faulkner, Hemingway, and Steinbeck:

The Sound and the Fury (1929) (that’s from Macbeth), Absalom! Absalom! (1936) (from 2 Samuel 19:4), The Sun Also Rises (1926) (from Ecclesiastes 1:5), For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) (from John Donne), Of Mice and Men (1937) (from Robert Burns), The Grapes of Wrath (1939) (from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” by Julia Ward Howe), East of Eden (1952) (from Genesis 4:16). They’re all quotes! “It is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.” And so on.

F. Scott “no Nobel” Fitzgerald does it too: Tender Is the Night (1933) is from Keats, This Side of Paradise (1920) from the comparatively obscure Rupert Brooke. Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel (1929) is from Milton. Over in England, Waugh’s Handful of Dust (1934) is from T.S. Eliot.

None of these books predate the 1920s. Before that, it’s hard to find “quote titles.” Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847) takes its name from John Bunyan, but it’s more of a reference than a quote; Vanity Fair, after all, is a place. There’s Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), which comes from Gray’s “Elegy,” and then pretty much nothing until 1918, when Theodore Dreiser wrote an obscure, unproduced play titled The Hand of the Potter—a quote from FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. After which comes the deluge.

You still see quote titles on occasion (though even Infinite Jest now qualifies as an old book), but the fad has passed.

*Footnote on Rough and Ready:

“What's your name, my lad?”

“Rough and Ready, sir.”

“What name did you say?” asked the clergyman, thinking he had not heard aright.

“Rough and Ready, sir.”

“That's a singular name.”

“My right name is Rufus; but that's what the boys call me.”

And yet, by my estimation, no human in the entire book actually addresses Rufus by the name Rough and Ready. The conceit that they might, though, is sufficient to make the book unendurable.

[Alger, Rough and Ready (John Winston, 1897) p. 11.]

•you’ll find all four: I wrote this list, clearly facetiously, without actually checking if it was true, but was gratified to learn, when I double checked at the eleventh hour before publication, that Lyrical Ballads does in fact conbtain:

1. the triumph of the imagination:

Therefore am I still

A lover of … all the mighty world

Of eye and ear, both what they half-create,

And what perceive…

(“Tintern Abbey”).

2. the splendors of nature: “Sweet is the lore which nature brings” (“The Tables Turned”).

3. wouldn’t it be interesting to be a shepherd?

When I was young, a single man,

And after youthful follies ran,

Though little given to care and thought,

Yet, so it was, a ewe I bought;

And other sheep from her I raised,

As healthy sheep as you might see,

And then I married, and was rich

As I could wish to be…

(“The Last of the Flock”).

4. vengeful ghosts: “Marinere,” of course!

Naturally, you’ll find other examples at your own leisure.

[Wordsworth & Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads (Oxford, 1998) pp. 115, 105, & 77.]

•“in the air,” as they say: By they I mean most particularly Vincent “the Bug” Bugliosi, the D.A. most famous for prosecuting Charles Manson, but who is relevant here for blaming (in his 1996 book on the topic) the O.J. Simpson verdict on the fact that the inevitability of O.J.’s acquittal was “in the air,” and the jury had to know about it. The Bug’s argument is more interesting than this bald summary makes it sound. [Bugliosi, Outrage: The Five Reasons Why O.J. Simpson Got Away with Murder (Norton, 2008) pp. 31ff.]

•end with the hero in peril: In fact, Ariosto’s sequel to Orlando, the unfinished, posthumously published Cinque Canti, ends with most plotlines unresolved, with, for example, the knights Ruggiero and Astolfo trapped in the belly of a whale and no escape in sight. Of course, these perpetual cliffhangers are due not to Ariosto’s innovations, but just due to the fact that he died before he could finish it; but such are the accidents that make up literature.

p. 233

•if we limit things to poetry: The mid-eighteenth century was a golden age of English prose fiction, of course, and everyone should find something to enjoy in the run between Fielding’s Shamela (1741) and Stern’s Sentimental Journey (1768). What happens after that is what I would call a fallow period for the novel, as sentimental and grotesque themes take over (with exceptions, such as Austen) until the 1840s or so (a controversial statement, which I would rather defend at length at another time).

p. 236

•among those most influenced by the French tradition: A more scholarly explication of the relationship between French culture and Pol Pot’s atrocities can be found (in song form) here.

p. 237

•pseudo-medievalist literary forger Chatterton: Chatterton, like many frauds and fakes (I’m looking at you, Ern Malley) was an excellent poet, but his teenage medievalism that fooled England is at times so transparently not anachronistic that…look, he used blank verse, a sixteenth century invention, in allegedly fifteenth-century poems, which is only one hundred years off, and which might conceivably fool people if the fact that blank verse is a sixteenth century invention were not one of the most widely-known facts in the history of versification.

•(Wordsworth): Originally I had written:

…Chatterton, dead by his own hand at age seventeen, who “with the food of pride sustained his soul / In solitude” (Wordsworth) when “black despair…was thrown / Over the earth in which he moved alone” (Shelley).

I got the quotes from Charles Wilcox’s 167-page introduction to the volume of Chatterton that I read, and I only learned later that, despite what Wilcox did not state but I thought implied, these lines do not refer to Chatterton at all. They are mostly correctly quoted, and are indeed from Wordsworth and Shelley, but at best they’re “inspired by” Chatterton in the same way Jon Bon Jovi’s Blaze of Glory album was “inspired by” the film Young Guns II. Fortunately, a little poking found that both Wordsworth and Shelley did indeed each write other lines about Chatterton, and they’re in the final text.

[Thomas Chatterton, The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton, with Notices of His Life, History of the Rowley Controversy, a Selection of His Letters, and Notes Critical and Explanatory Vol. 1 (W.P. Grant, 1842) p. cxxxviiii.]

p. 238

• “lost cause”: “I replied that only lost causes were of any interest to a gentleman.” –Borges, “The Shape of the Sword” (1944). [Borges, Collected Fictions (Viking, 1998) p. 139.]

•Norman Mailer produced “the list”: Also, Mailer said, Heidegger is hip and Sartre is square—not sure I understand that one. [Dinerstein op. cit. p. 229.]

•what is square: It’s worth noting that at one point, “square” had the specific meaning of someone who did not appreciate jazz. In High Society (1954), the tragedy is that “now the silly chick [Grace Kelly] is going to marry a square.”

As late as 1970, The Aristocats can inform us that “a square with that horn / Makes you wish you weren’t born / Every time he plays” (hear it here)—but the movie anachronistically takes place in 1910, so good luck figuring that out.