There are two ways, as everyone knows, of running an authoritative study comparing apples, say, and oranges. One is to survey a large number of apples and oranges and run a chi-squared test and get a p value and do a bunch of other things I knew how to do in college but have since forgotten. The other is to find the Platonic ideal of an orange and the Platonic ideal of an apple and compare them. This latter method is quicker.

On pp. 104–5 of Impossible Histories, I mention, in passing, that over the last hundred years or so, we, as Americans (who are my presumed audience) have been getting stupider. I do understand that IH is brimful of unsupported assertions, the evidence for which wound up on the cutting room floor as I pruned my endnotes to the bare minimum required not to be called a plagiarist—but perhaps I can support this one. I mean, certainly I have been getting stupider, in the sense that I can no longer run a chi-squared test. As Stephen Brust famously wrote, “Everyone generalizes from one example. At least, I do.”

Let’s seek out some cases from the Realm of Forms…

ii. Case A: A shill

In the late nineteenth century, ten years before Henry Ford, a man named Edward Stratemeyer applied factory churn-’em-out methods to children’s literature. By providing formulaic outlines to anonymous hacks he could keep a steady stream of product flowing from the presses and into the hands of young Americans.

(Please note that I am not using the word “hack” pejoratively—many of my heroes were hacks.)

Many of the Stratemeyer Syndicate’s creations—including the Bobbsey Twins and Tom Swift but most especially the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew—are familiar and beloved today. A hundred years ago, of course, they were hated—not by children, who loved them, but by librarians and educators.

Stratemeyer was the literal apprentice of Horatio Alger, the undisputed king of nineteenth-century children’s-book hacking. Okay, maybe apprentice has some technical meaning that Stratemeyer did not literally fulfill, but I mean Stratemeyer yanked posthumous rough drafts from the stiffening hands of Alger’s corpse and finished them (anonymously). He “finished” so many Alger drafts that almost certainly some of them are pure Stratemeyer, ghost written in the most spectral, from-the-grave sense of ghost.

Now Alger was himself a figure of contempt among those with “taste.” Alice M. Jordan, in her 1948 survey of children’s lit from the previous century, dismisses Alger’s books as “cheap and tawdry, his characters impossible, his plots repeated endlessly [etc., etc.].” Then she obliquely accuses Alger of being a pederast, which I guess he probably was.

One of the books Stratemeyer wrote under his new pen-name of Horatio Alger was Randy of the River; or, The Adventures of a Young Deck Hand (1906). Hero Randy’s nemesis is a vile bully named Bob Bangs, who (the narrator explains with scorn) is addicted to “cheap paper-covered” dime novels, including a trashy piece called Bowery Bob, the Boy Detective of the Docks; or, Winning a Cool Million. The narrator goes on to assure us that “the absurdity of the stories was never noticed by [poor Bob Bangs, who is also ugly], and he thought them the finest tales ever penned.”

We don’t learn much more about Bowery Bob, but it should go without saying that its plot resembles nothing so much as a Horatio Alger novel’s. Its very title is a mashup of several books Alger published, one element from each: Bob Burton (1888), Ben Bruce: Scenes in the Life of a Bowery Newsboy (1892), Dan the Detective (1880), Ben the Luggage Boy (1870—Ben works on the docks), etc. Randy himself ends up on the Bowery, where if he not quite solves a mystery at least thwarts a thief. Winning a Cool Million sounds so much like a default Alger title that when Nathanael West wrote a humorous travesty of Alger’s fiction in 1934, he called it A Cool Million.

But we’re not here to talk about the books Stratemeyer wrote as Horatio Alger! We’re here to talk about the books Stratemeyer didn’t necessarily write, under a host of pseudonyms, for the Stratemeyer Syndicate. These pseudonyms are names to conjure with, and your library’s shelves are filled with volumes by Caroline Keene and Frank W. Dixon, neither of whom was a real person, or even a stand-in for one real person, but rather a rotating cast of hired guns. But when the “Keene”’s and “Dixon”’s books started coming out, in 1930 and 1927 respectively, your library’s shelves would not have held them. Librarians refused to carry the books; teachers refused to teach them. There was a real fear that if children read Stratemeyer books, they would get dumber.

Lucy M. Kinloch, writing for The Elementary English Review in 1935, singled out a Stratemeyer series as “an orgy of the ungrammatical commonplace,” and called such books “a real menace to the child’s reading future.” She suggested “it would be better for a child not to read at all than to waste his time and deaden his mentality with crude language, impossible and melodramatic situations, and a commonplace vocabulary,” and fantasized that perhaps “this trash will find its way into the furnace, where it belongs.”

Meanwhile, the chief scout librarian of the Boy Scouts proposed that such books be labeled with a warning label reading: “Guaranteed to Blow Your Boy’s Brains Out.”

Let us repeat. These books are so bad, that just reading them make you less literate (and possibly dead).

iii. Case B: The best and brightest

In 2018, a Rhodes scholar and Yale-educated lawyer who also happens to be a former president of the United States, teamed up alongside a champion of literacy with an advanced degree in literature who also happens to be America’s best selling author to produce a #1 New York Times bestselling book. Of course we’re talking about The President Is Missing by Bill Clinton and James Patterson.

I have nothing else interesting to say about this book.

iv. The comparison

Soooo I was going to compare the first sentence of the first Hardy Boys book and the first sentence of The President Is Missing, but both books open with dialogue, so that doesn’t work.

(The HB books were later revised, but I’m pulling the original, unrevised, reviled edition from Google books.)

But I would just ask you to read the first couple of pages of each book. I’m not saying Hardy Boys is good (it isn’t) or that it’s better than The President Is Missing (that’s subjective), but just looking at the prose, one book is clearly more challenging than the other. Look at this sentence (from the second page of The Tower Treasure):

These were the Hardy boys, sons of Fenton Hardy, an internationally famous detective who had made a name for himself in the years he had spent on the New York police force and who was now, at the age of forty, handling his own practice.

Would Clinton/Patterson even be capable of conjoining two subordinate clauses like that? Is any sentence in TPIM this literate?

Compare any paragraph from the opening of Tower Treasure with this unproofread, vague, illogical, barely grammatical mess, the first non-dialog paragraph in TPIM.

The sharks are circling, their nostrils twitching at the scent of blood. Thirteen of them, to be exact, eight from the opposition party and five from mine, sharks against whom I've been preparing defenses with lawyers and advisers. I've learned the hard way that no matter how prepared you are, there are few defenses that work against predators. At some point, there's nothing you can do but jump in and fight back.

That first full stop is eccentric, in that it creates a sentence fragment (“Thirteen of them”) in the next sentence—but, hey, that’s a stylistic choice. Except, nightmarishly, the sentence fragment just keeps going, tacking on another clause (“sharks against whom”)! What is that about? In one sentence we’re preparing defenses; next sentence: Defenses don’t work! So one has to “jump in” (into what? the fight? the water?) and fight back (can one not fight defensively? doesn’t “fighting back” suggest a defensive stance?). I can sort of get what Clinton & Patterson are trying to convey in this paragraph, but it’s muddled, awkward, and ugly.

I don’t even think the Hardy Boys books are that good! I’ve never read The Tower Treasure, but I’ve read other Hardy volumes, and Nancy Drew, and the Bobbsey Twins, and etc., and I make no claim to any of them being fine literature. But they are, I can affirm, filled with grammatical English sentences arranged in a logical order to convey meaning.

The President Is Missing I have read all the way through. It is consistently subliterate passim. Many paragraphs are just one word long.

Ah, but The President Is Missing is a potboiler. Who cares if its full of sentence fragments and tortured syntax? No one would care, were it not for the fact that this bestselling book for adults is clearly far below a level of writing that experts believed could render children illiterate should they by chance be exposed to it. We’re not even comparing children’s books with children’s books. We’re comparing an adult book to children’s books, and the adult book is lacking.

We’re comparing a prose level so stupid that it made children stupider in 1927 to the best that two of the most gifted and educated Americans of 2018 could produce.

1927 vs. 2018. Ninety-one years to bring us down to this level.

v. A lament

Let me say that I take no joy in the inevitable conclusion that we have, in fact, grown stupider. I’m not smug about it. I’m not dancing around, shrilling, Look, you rotten kids! See how [x] has rotted your brains! That [x] was video games when I was young, and now it’s on to being something else, but whatever it is, it’s hardly a cause for celebration.

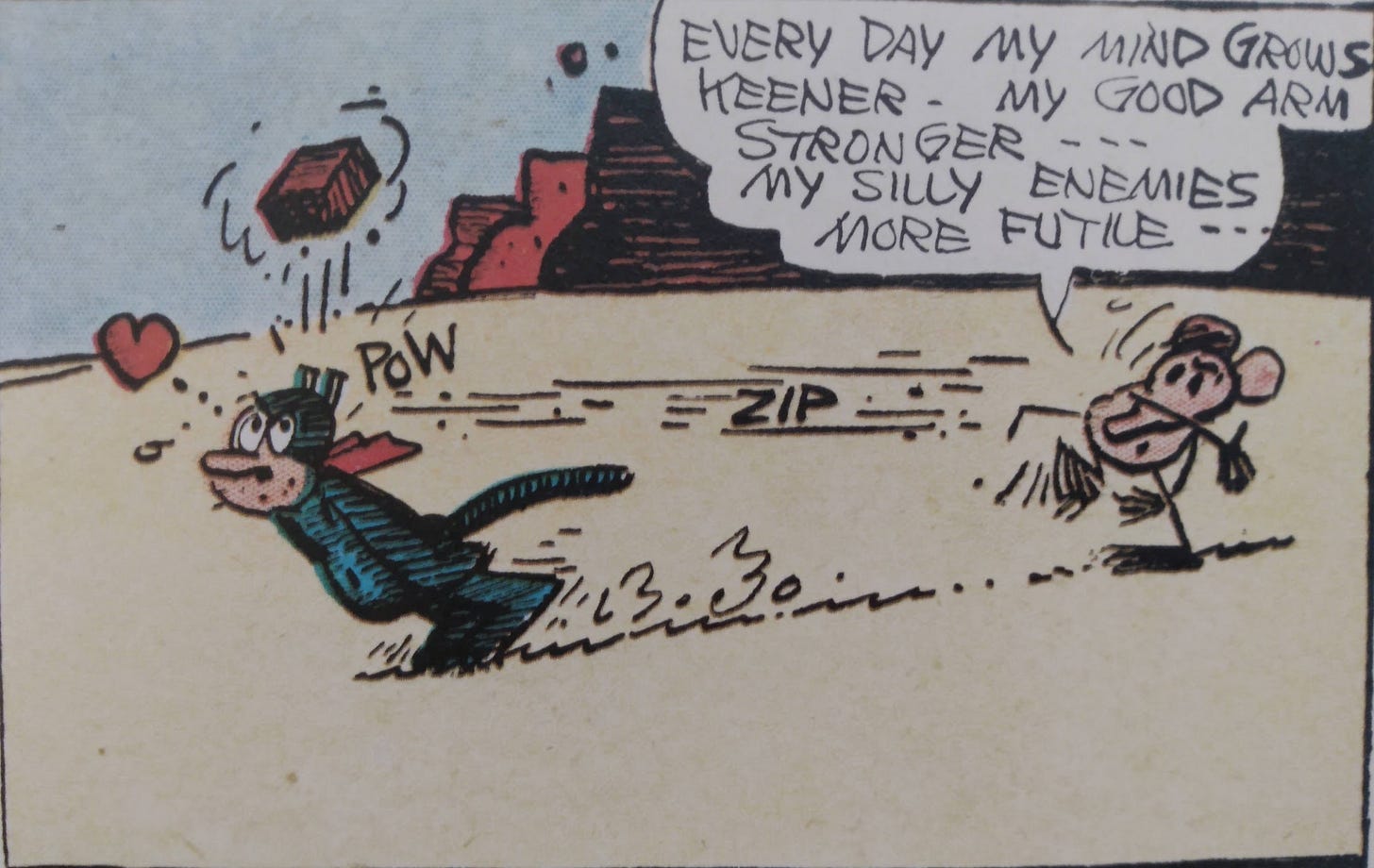

We should be getting smarter! It’s happened before: Certainly the average European, between the late ninth and the late nineteenth centuries, got smarter. Ignatz Mouse one said, “Every day my mind grows keener—my good arm stronger—my silly enemies more futile—” and this is precisely the kind of growth mindset we could enjoy if we weren’t spending all out time tripping over our own folly.

[Sources: Stephen Brust, Issola (Tor, 2002) p. 211; Alice M. Jordan, From Rollo to Tom Sawyer (Horn Book, 1948) p. 32; Horatio Alger, attr., Randy of the River; or, The Adventures of a Young Deck Hand (Grosset & Dunlop, 1906) pp. 30–31 & 220–21; Lucy M. Kinloch, “The Menace of the Series Book,” The Elementary English Review, vol. 12, no. 1 (1935) [www.jstor.org/stable/41383173] pp. 11, 10, 9, & 11; Boy Scouts: Melanie Rehak, Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her (Harcourt, 2005) p.97; Frank W. Dixon, attr., The Tower Treasure (Grosset & Dunlop, 1927) p. 2; Bill Clinton & James Patterson, The President Is Missing (Grand Central, 2019) p. 3; Ignatz Mouse: George Herriman, Krazy Kat 3/20/1938.]

What if Nixon contested the 1960 election?

What? •Richard M. Nixon, quoted in Gravity’s Rainbow (1973).