(As always, I encourage you, if you like my writing but wish an editor would “tone it down,” to indulge in some of my books, in which a sober editor has done just that.)

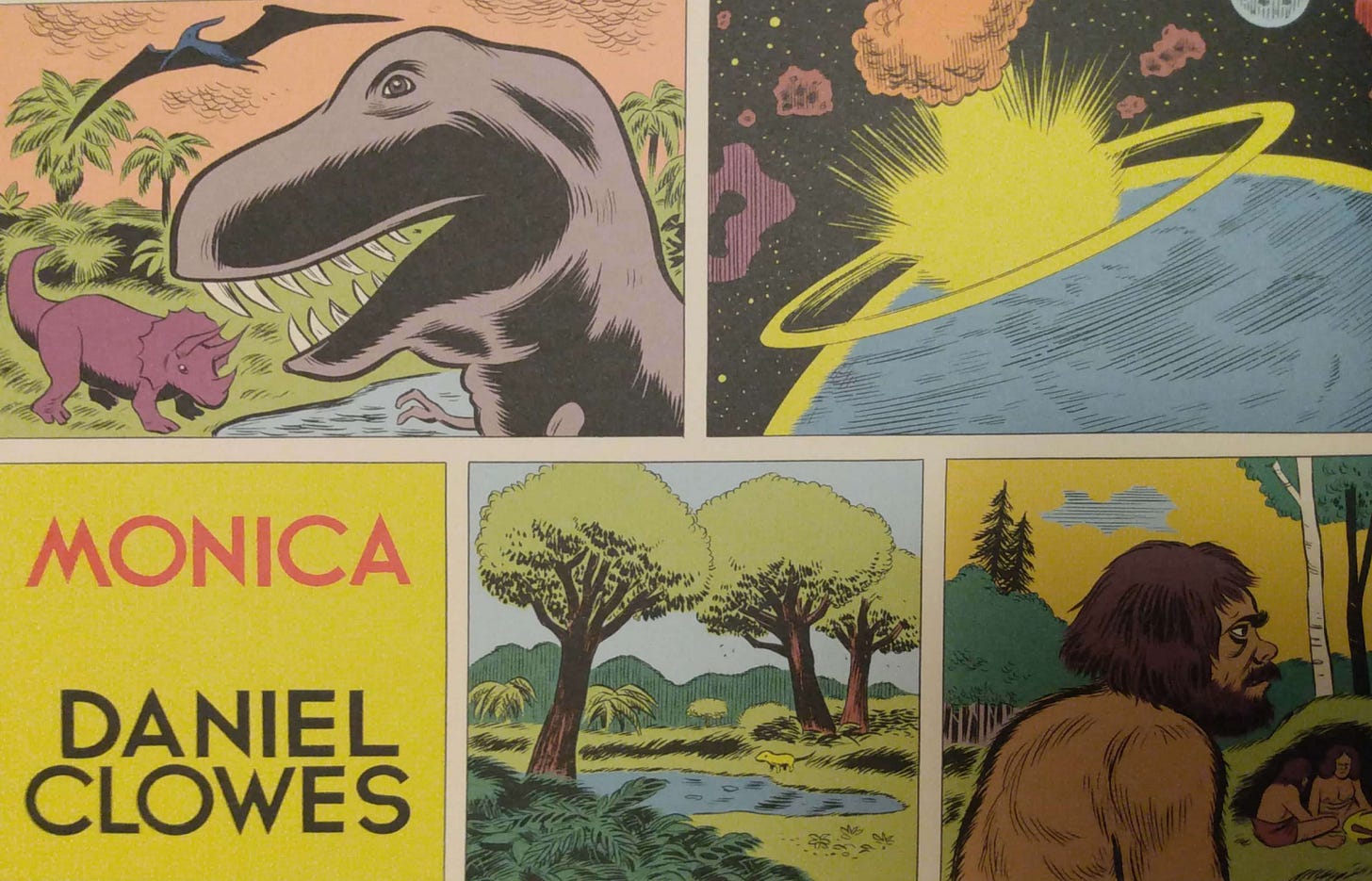

I love Daniel Clowes’s new graphic novel Monica, but I don’t understand all of it. In part, this is because I’ve only had a week or two with the book, and in part because some aspects may be literally ununderstandable. Clowes is on record (speaking of David Boring in an interview I once read but can no longer locate) that he finds mysteries interesting and the solutions of mysteries dull. The many mysteries of Monica’s life may offer no tidy solution.

What I want to try to figure out here, in this prolegomenon to any future Monica reading, is simply what “actually” happens in the book.

You can put “actually” in as many scare quotes as you want. The book is fiction, for one thing. But in the world of Monica, some panels are obviously not meant to be interpreted as reality. For example, the first panel on page 61 is clearly labeled a dream. The fifth panel is a symbolic depiction of a whale brought down by “a vast swarm of leeches and lampreys.” Even the naivest reader would encounter these panels as a fantasy outside the “real” narrative. The other panels on the page are presumably depictions of events that we are supposed to suspend our disbelief over—insofar as we agree to pretend the fictional character of Monica exists, we might also agree to pretend she visits the office of her candle company. (We might not, but certainly in a naive reading we do.)

I’m not saying this to spiral down into an abyss of narratological theorizing. I am in fact saying this precisely to avoid spiraling down into an abyss of narratological theorizing. I’m just trying to figure out what “happens” in Monica.

It’s not the case that I’d claim this is the best method to understand a text, but it’s generally a fine first pass, and that’s where we are here.

Monica has nine chapters: Foxhole, Pretty Penny, The Glow Infernal, Demonica, The Incident, Success, The Opening the Way, Krugg, and Doomsday. Let’s tackle them one at a time.

Oh, and everything that follows is a spoiler.

Foxhole

Probably very little of what I have to say will make sense if you haven’t read Monica, so you should go and read Monica, but if you haven’t, here’s the plot summary of chapter one: Two soldiers chat. There will be no further chapter summaries. (Go read Monica.)

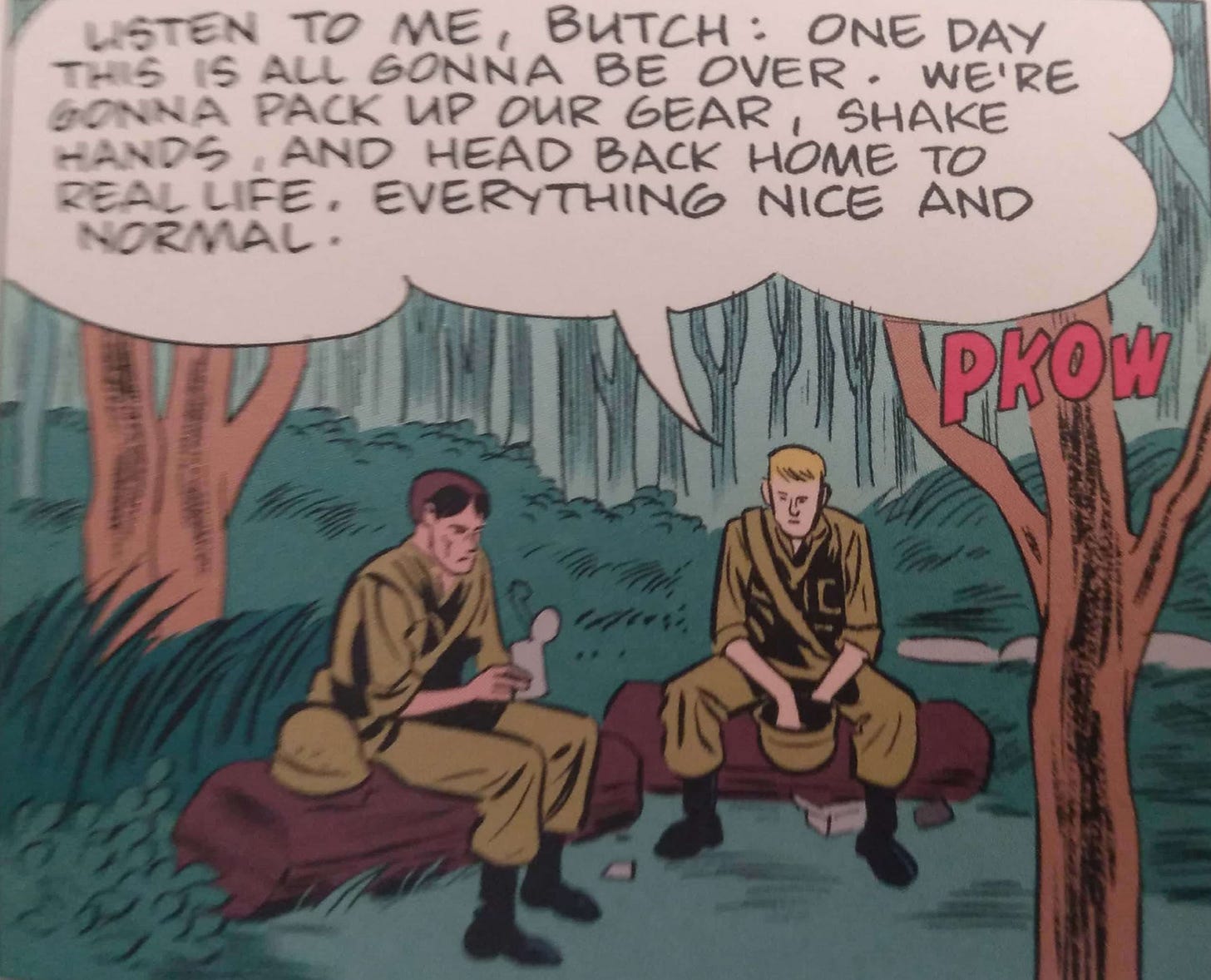

There is nothing overtly implausible in this chapter, and surely one’s first impression is that its events are, in the world of Monica, true. Johnny and Butch are the only “witnesses” to these events, but it is scarcely unusual for a chapter in a book (even less so in a comic book) to be presented by an omniscient narrator. Why could this not have happened?

There’s something a little strange about the titular foxhole. Look closely—in the first panel of page 3 (the first page of the chapter), Butch is sitting in the foxhole, his elbow resting on the edge. By the next page, Butch and Johnny are sitting on some rocks (three rocks!) next to the foxhole, their feet in the hole—which is only ankle deep (panels 5 & 7)! By page 5 the foxhole has completely disappeared (panel 1)!

On closer investigation, there’s a perfectly naturalistic explanation for this strangeness. The foxhole is of two differing depths: a deep part and a shallower “shelf”; this is most obvious in page 3, panel 4, which depicts Johnny sitting on the shelf, his feet in the pit. On page 4, Butch and Johnny are resting their feet on the shelf, which is why the hole now looks so shallow. By page 5 they have moved away from the foxhole (it’s visible in the background of the first panel) and are sitting on logs. The logs are arranged similarly to the rocks, so at first glance it looks as though the two have not moved. And yet they have, so of course there’s no foxhole in front of them!

The effect on the reader is the appearance of a deep foxhole that extrudes (as though birthing) two soldiers and then grows shallower and closes up. But this apparent extravagance is belied by the simple explanation that two soldiers slowly climbed out of a foxhole, moved a few yards away, and then sat down again. Nothing could be more prosaic.

An apparent mystery, an apparent fantastic happening, proves to be straight reality. Will all apparent mysteries in Monica resolve themselves so easily? (No.)

On the other hand, Butch accurately predicts the ending of the book, which is a strange thing for a realistic character “really” to do. But believable and possible, all things considered.

And yet, as we will see, this story must in fact be a fiction, presumably written by Monica.

Pretty Penny

Chapter two is narrated in the first person by Monica, a character who is not yet born when the chapter starts, as she outlines her mother’s experiences as a flower child. None of this is unusual, either; you don’t have to be Tristram Shandy to talk about the world before your birth and Monica later explicitly tells the reader (p. 14 panel 2, e.g.) that she has researched this part of her mother’s life.

Who told her that her mother and boyfriend/hippie gateway Leonard Krug sat somewhat naked eating Alpha-Bits and listening to tunes, though (p. 8 panel 5)? Is this is product of Monica’s research? A memory Penny shares with her? An extrapolation (it’s a plausible scene, isn’t it?)? Three panels later Penny is looking in the mirror and saying, “I can’t believe this is me.” Is it? Should we believe this is she?

With the exception of three or four panels (p. 8 panel, p. 11 panel 5, & p. 24 panel 1—and mmmmaybe p. 23 panel 4) everything in this chapter is perfectly plausible as “reality.” The third of these panels (easiest) is explicitly a dream, a flower with a human face. Is the first one a television program (with the obvious double entendre from Penny)? TV screens are displayed, sometimes prominently, throughout this chapter (Hogan’s Heroes, Laugh-In—p. 14 panel 5 & p. 15 panel 7).

But the second one is clearly Leonard depicted as an acid-influenced arch-hippie in Beatle garb. Is this how Johnny’s parents view Leonard? If so, it’s kind of a strange viewpoint—Leonard looks both less threatening and less Jewish in the acid panel than he does in his every other appearance. Three panels later, Monica admits: “I don’t even really know what he looked like, to be honest.” She goes on, “This isn’t his story, is it?”

And yet chapter 8 is his story. (Also note that Leonard is more or less predicting the book’s ending, although perhaps less precisely than Butch does.)

Monica (or Clowes?) illustrates her meditation on Krug’s appearance with a picture of Penny, a black and white photo. This photo, or perhaps several like it, would be the way that Monica knows what Penny looked like in the pre-Monica days. (She later uses the photo, creased now, to show aging hippies as she grills them about the past (p. 69 panel 7).)

Much of the story (so far) has dealt with characters’ fantasies about other characters. The opening page of “Pretty Penny” features Leonard riffing on his impression of Johnny, a man he’s never met—he imagines Johnny to be a hillbilly. In the previous chapter, Butch had his own fantasy about Johnny as a Buick-driving elite (“This is your world, Johnny etc.” (p. 5 panel 4)). (In panel 5 of page 3 Butch also has his own fantasy about how Johnny sees him.) Of course, Monica’s impression of Johnny has to be mostly fantasy, too.

The relationship of the entire narrative to reality is, we keep being reminded, tenuous. When Monica’s narration makes a hesitant suggestion about Penny’s motivations (“Possibly it was a fuck you to my ‘dad’…or her parents, or just to America in general”), Penny, on panel and as it were diegetically, responds “Fuck you, America in general” (p. 14 panel 1). Is she…answering her daughter’s question? Is Monica imagining how Penny might answer her daughter’s question? If Monica does know how her mother would answer the question, why has she given three possibilities (dad/parents/America)? Does Monica think she knows how Penny would answer and yet not believe this to be her true motivation? Why does Monica think her mother kept the baby?

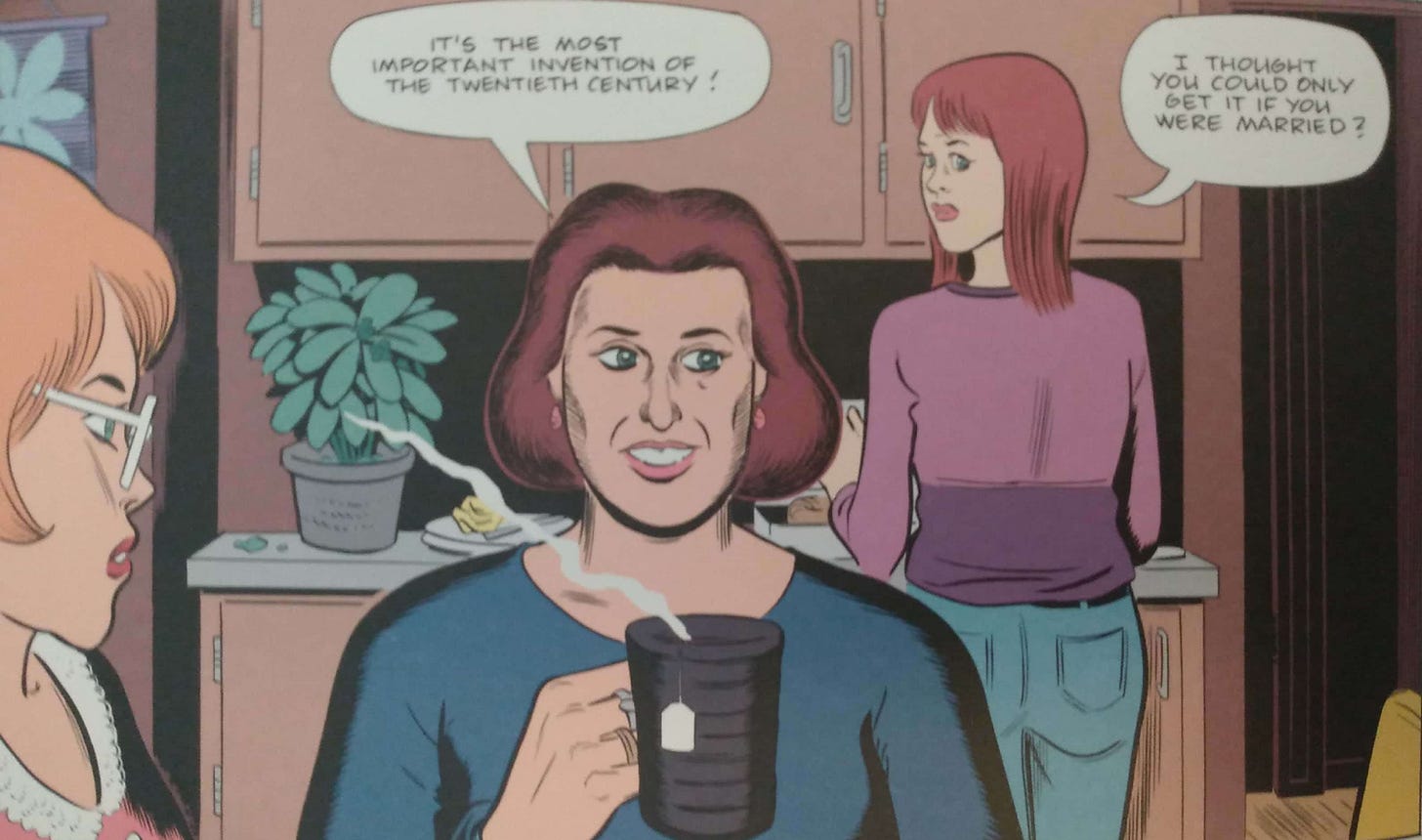

Because there was going to be a baby. Despite her use of the Pill, spermicides, and abortifacient herbs, Penny gets pregnant. Note that on page 12 (panel 1) a friend of Penny’s proclaims the Pill to be “the most important invention of the twentieth century!” a bold claim in a book whose copyright page has already provided its own list of nukes, rock and roll, Sputnik, and television. Despite its alleged importance, the Pill doesn’t work this time! This is a pregnancy that cannot be prevented! Perhaps that is significant.

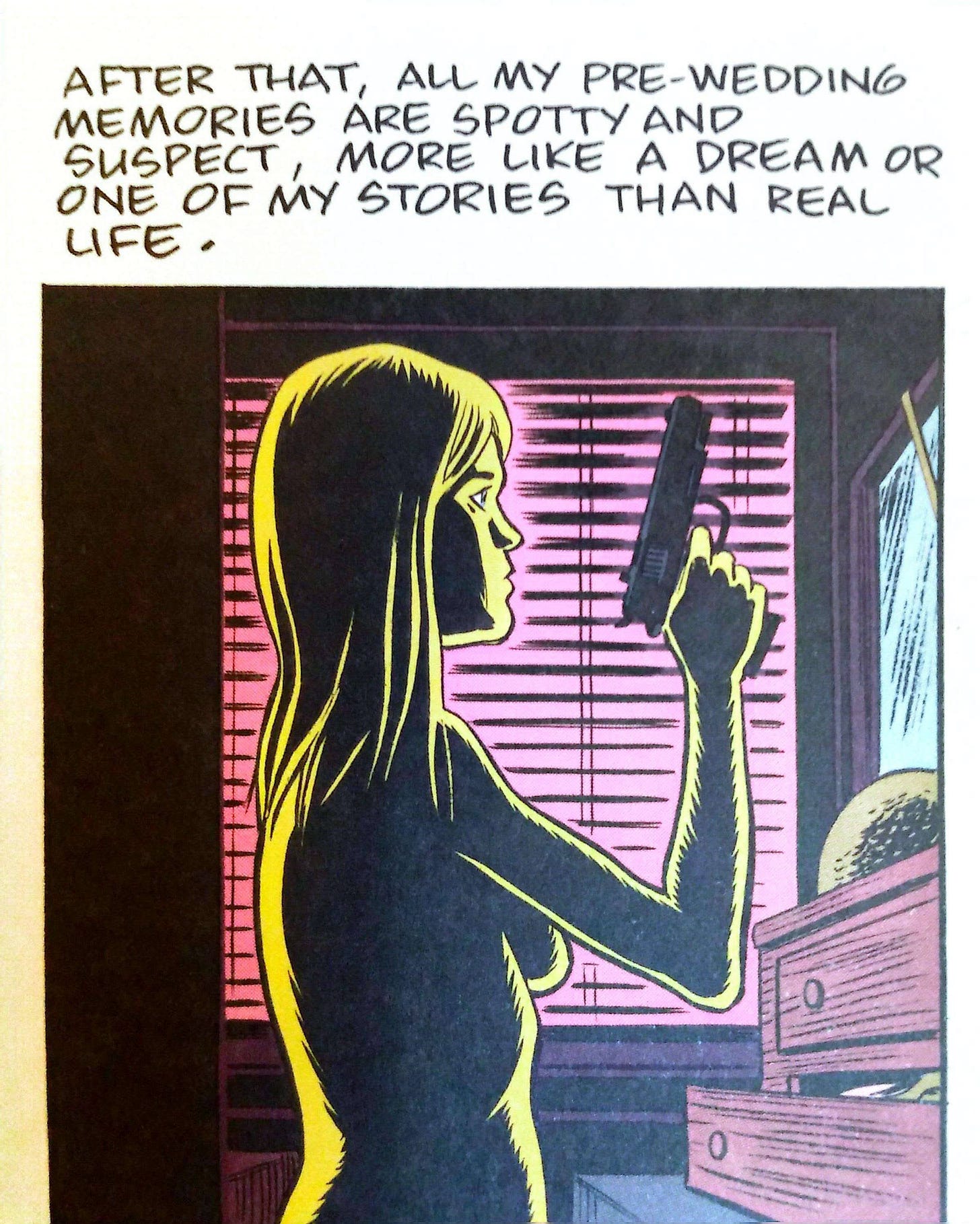

The early days of Monica’s life are (again, explicitly) researched—the speaker on page 22, panel 4 is Johnny, on the porch where Monica interviews him on page 63—but Monica is soon old enough to be able to rely on memory. And yet childhood memories quite naturally are incomplete (p. 16 panel 4) or inexplicable (p. 24 panel 5). “All my pre-wedding memories are spotty and suspect, more like a dream or one of my stories than real life,” (p. 23 panel 4) Monica says, which is perhaps an innocent statement about memory and perhaps something more revealing.

Monica’s final statement in the chapter’s final panel (after being abandoned by her mother) is: “From that moment on I lived a normal life, happy and safe from harm, but I never saw my mother again.” If the rest of the book is to be believed, “normal life,” “safe from harm,” and “never saw” are all false.

The Glow Infernal

What follows is a chapter that would have fit very nicely alongside “The Gold Mommy,” say, in a mid-’90s issue of Clowes’s comic Eightball.

The prose here is overwrought and overwritten. “Would there be no abatement to my mounting dread?” “O misfortune! O sorrow!” Even the vocabulary is more precious: idyllic, gloam, a-shiver, sistren (respectively p. 26 panel 5, p. 32 panel 4, p. 28 panels 4, 5, & 6, & p. 33 panel 1). The situation is melodramatic and fantastic, and the fantastic elements do not gel with the fantastic elements in other chapters. This must be, as Monica puts it, “one of my stories.”

In William Avis’s search through a crumbling town for his absent father, we can see Monica’s search through the crumbling civilization of the 1960s for a father figure (“I’m afraid you’re going to grow up thinking…that you even need some fucking man in the first place,” Penny says to Monica, getting it half right (p. 20 panel 2)), or her search for her actual father (through a world that is perhaps crumbling in Clowes’s default worldview and perhaps about to disintegrate in the final pages of Monica). “Would my own father even recognize me?” William worries (p. 25 panel 3). Monica’s own father “has never even seen me,” she reports (p. 14 panel 1).

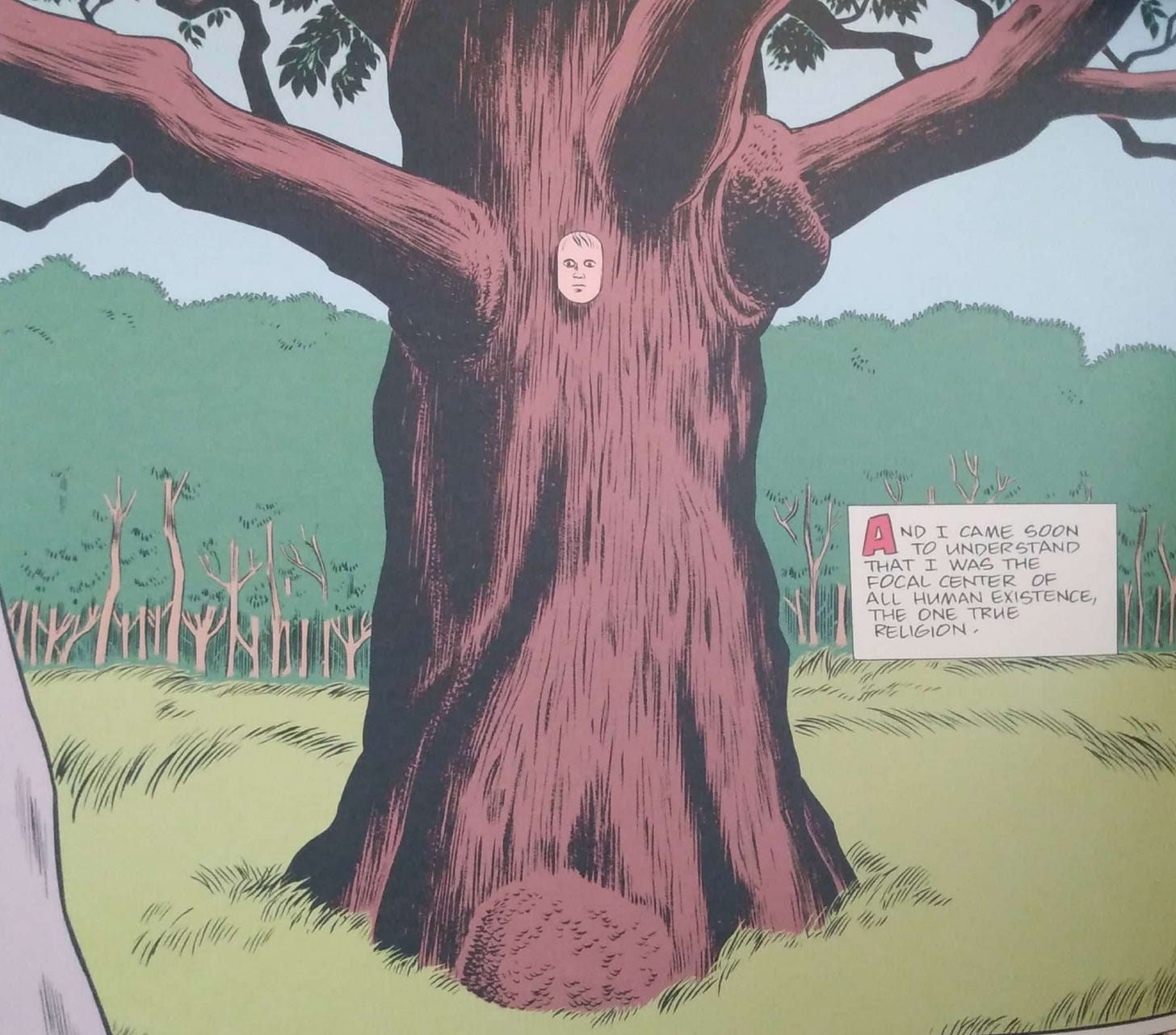

The story is replete with details that echo Monica’s life, although not necessarily the life as we’ve see it so far. The cult members’ and William’s haircuts (they’re identical!) are the most obvious. When Monica visits Johnny she reports that “his place looked like it had once been a nice suburban home before something, some awful catastrophe, had brought ruin and despair” (p. 63 panel 5), a clear parallel to William’s statement that his father’s house “stood…in grievous disrepair” (p. 26 panel 4)—the catastrophe here unambiguous. Perhaps it is premature to worry over these details, and we should simply note William’s fate, after his subterranean holocaust. “I was the focal center of all human existence, the one true religion” (p. 36 panel 1).

Here his face in the tree mirrors Monica’s childhood dream of her face in a flower (p. 24 panel 1), the dream she had on the night of her second abandonment. The sistren of Vera Van Thorne are known as the Daughters of the Hollow Cypress, and Monica buries grandpa (via his radio) under a cypress tree (p. 48 panel 10)—but the tree that William is part of is not a cypress tree.

For the first time, the pages are cream.

Before chapter one

Let me interrupt myself; because the book does not really start with chapter one, “Foxhole.” First there’s a cover, then the front endpapers and title and copyright page etc. The front cover shows Monica herself superimposed on…the night sky? That’s what I thought at first, but the sunburst at top left should blot out the night sky. Looks more like Monica in outer space. Presumably, based on the images scattered throughout the endpapers, etc., this is outer space before the assemblage of Earth. Perhaps the upper left is the big bang? Perhaps in this early moment, the stars are all much closer together.

The endpapers show the primordial Earth.

And then we get, in sequence, a rapid tour through every significant event in (pre)history. Unicellular life. Vertebrates emerge on land. The Age of Dinosaurs. The KT extinction. Early mammals/Eocene reforestation. Cavemen. The rise of Egypt. The crucifixion. The Black Plague. Spain arrives in the New World. Shakespeare/Hamlet. The Industrial Revolution. The US Civil War. WWI. Hitler. The atomic bomb. The emergence of rock and roll (as epitomized by Little Richard). The Space Race (as epitomized by Sputnik). Kennedy’s assassination (via Zapruder). The reign of television (as epitomized by The Beverly Hillbillies). The television brings us to the 1960s (BH debuted before JFK died, but it ran long after). This is perhaps a view of history that skews towards the modern, and is perhaps (rock, sitcoms) Boomercentric, but it’s a pretty good whirlwind tour. Turn the page to find out what historical event will be depicted next!

Turn the page and you see it’s the Vietnam War (via “Foxhole”), which seems fair (if Boomercentric).

Or you don’t, really. The Vietnam War is not the first thing you see. The first thing you see is the table of contents. In other words, what is so important that it deserves to be listed alongside pyramids, Shakespeare, and WWI? This whole book.

For that matter, what comes between the end of the dinosaurs and the rise of mammals? Monica. And also incidentally Daniel Clowes (panel 5, page i or maybe iii or iv?).

Anyway, if we’re looking for “the focal center of all human existence” we should probably look around here.

Demonica

That’s all been easy, hasn’t it? There’s Monica and there’s Monica’s fiction, and nothing to worry about.

But let’s start worrying. In this chapter, for the first time outside of an acid trip, something literally fantastic, not faux foxhole fantastic, happens. Already Monica is giving the lie to her chapter-two assertion that her life would be normal. She’s hearing her dead grandfather on the radio.

The deaths of her grandparents, whom she calls momma and poppa, Monica explicitly compares to abandonment by her parents (p. 38 panel 4), so her postmortem encounter with Poppa is in some ways the reunion with the absent father she’s long craved, as well as a forging of the “implausible bond” she’d failed to achieve with her grandfather in life (p. 39 panel 9). Is this incident mere wish-fulfillment? By page 55 (panel 1), Monica has come “to accept that the events of those impossible weeks at the lake house were some coma-induced hallucination, a long complicated dream.” But that’s not what she thought at the time (or not what she thought she thought at the time?). The key to chapter three is doubtless Monica’s insistence that she is now privy to “the most important thing in the history of the world” (p. 43 panel 8). This is certainly better than her previous fantasy or a few days before, that the next door neighbor, is “possibly (probably) out there masturbating” over the view into sleeping Monica’s cabin (p. 39 panel 11).

Now, we all know that dead people do not speak through radios. But comics, like much of literature, are full of impossible events, and the fact that irradiated spiders cannot, in fact, grant “spider-powers” has never caused me to assert that the last sixty years of Spider-man continuity are nothing more than Steve Ditko’s fever dream.

But Monica’s reliability (unlike Spidey’s?) is always in question. On page 39, Monica says, “That’s how it is with the locals. Once the summer’s over they don’t have to be nice any more” (panel 1), but on page 43 the local at the lunch counter is friendly and chatty. Her vow (“I would never tell my secret. Not to anybody ever” (p. 43 panel 7)) is, possibly by page 55, panel 1, and certainly by page 62, panel 4, broken. And the doctor on page 54, panel 6, directly contradicts key details of Monica’s story.

If your boyfriend disses you at your lowest moment…surely one might fantasize that he comes crawling back begging forgiveness. Later Monica insists she has confirmed that the boyfriend did come (p. 55 panel 2), but are we to believe her? That panel depicts the grandfather floating in…space? over a fluffy cloud? He looks much younger than he does in his only other “onscreen” appearance (p. 24 panel 8). Surely the encounter with boyfriend Nathan, complete with burning hand, “a moment of perfect stasis”, and “pure elemental desire” (p. 45 panels 4 & 6), seems more of a fantasy than anything else.

Note that Monica’s grandfather’s fretting over a Jewish boyfriend mirror’s Leonard’s idea of Johnny’s family fretting that Penny “was a-huggin’ an’ a kissin’ on a damn Jew” (p. 7 panel 2). Did the grandfather’s fretting inspire Monica’s imagination about her mother’s postcoital conversation? Or did things she heard about Leonard’s statements about Johnny inspire the fantasy about grandpa?

Regardless, no, I was wrong before, and certainly the key to chapter three is the end, as the car quietly and from a distance can be seen careening off the road. A suicide attempt, presumably. The car’s final run starts on panel 3 of page 48, and makes intermittent appearances as, in flashback, Monica’s grandfather slowly but inexorably slips away. The narration for the aforementioned panel 3 is: “Over the next few months, his signal started to fade”—emphasizing the relationship between the grandfather’s final death and Monica’s approximate one.

If the radio ghost “really” speaks from beyond, does Monica try to kill herself because she has been abandoned (for a fifth time!) by someone she thought had returned to her?

If the radio ghost is Monica’s pretense, did she imagine its appearance while sitting alone in a cabin, only seeking to kill herself when she was unable to maintain the calming fiction? Or was the whole thing a post-coma invention, to cover the real reason for the suicide attempt—something mundane and/or embarrassing? Was Nathan’s visit actually a bad experience, bad enough to prompt a suicide attempt one is later ashamed of?

Or is the car crash a genuine accident? On page 54, panel 6, a doctor claims Monica skidded on black ice (although he kind of looks like he’s feeding her a line, trying to persuade her, doesn’t he?). The moment before hearing her dead grandfather’s voice Monica compares to “when your car spins on the ice” (p. 41a panel 4).

That’s not the first, but it’s certainly the most ostentatious, appearance of a hummingbird as grandpa’s soul departs (page 48 panel 9). The first appearance is on page 6, above the memorials of those who were “lost during the making of this book.”

Excursus on page numbers

Perhaps here is the place to flesh out that citation “p. 41a” above. I put “41a” because there are two page 41s. There is no page 42. The book keeps going with 43.

The returning 41/41 happens just as Monica undergoes a returning herself—this is when her grandfather, or his voice, returns from the dead. On the page that should be 42 she is addressed as Demonica for the sole time.

The only other page-number irregularity I have found is on page 23, in which the 23 is justified towards the spine of the book, as opposed to at the edge. (If that sounds unclear, just look at the bottoms of page 23 and any other page, and you’ll see what I mean.) Page 23 is the page on which Monica takes the crumpled pamphlet out of the garbage, an act that propels her mother into The Opening/Way cult. Is the unmooring of the page number 23 a sign of some kind of disjunction, the moment when Monica’s life spirals off in a new direction? A few pages later, Monica says, of her last moments with her mother: “In my memory, the uncrumpled pamphlet was next to me on the back seat, but that always seemed weird” (page 24 panel 5). How weird does it seem? Weird like it never happened? Weird like it should never have happened? Weird like it could never have happened?

The missing number 42 is, of course, in the cult classic SF series Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the answer to life, the universe, and everything. Is its omission a sign that there will be no answer?

In the much more cult and slightly more classic but not more SF series Illuminatus!, the number 23 serves as a sign of the overarching pattern that connects disparate items in a paranoid reading. Is its being out of place a sign that paranoid readings are out of place here? (If so, the warning is kind of contradictory, no?)

Or is it just easy to make a mistake when you’re hand-lettering galleys?

The Incident

And now back to Johnny, once again with a gun in his hand, but stateside this time. With his fake beard he looks a little like the gravedigger from the Hamlet panel in the endpapers (note that old Johnny will appear with a shovel on the back cover, looking at his younger action-packed self (and immediately following another, more prominent appearance of a shovel, this time wielded by Monica)).

I hope it goes without saying that the events depicted in the first few panels of this story owe more to the conventions of genre fiction that to the careers of “real” private investigators. Nothing wrong with that—we’re knee deep in genre fiction here, of course—but nevertheless, I think it’s clear that once again we’re reading one of Monica’s stories, a fantasy about her not-quite stepfather’s life. If Butch and Leonard can fantasize about what Johnny is really like, surely Monica can as well. The story is similar to “The Glow Infernal” (and would also have fit comfortably in mid-’90s Eightball), with an isolated town (isolated by avalanche or police blockade) beset by strange tragedy, filled with townspeople who will not talk. Just as William had searched for his father, the “kid” searches for his mother.

The “kid”’s last name, like William’s, is Avis, and “Mrs. Pine, the maid” could even be the mother of “The Glow Infernal”’s Florence Pine, one of the Daughters of the Hollow Cypress (see p. 52 panel 7, p. 26 panel 2, p. 51 panel 1, & p. 29 panel 1). She even looks like Mrs. Van Thorne, but while Mrs. Van Thorne has fallen from prominence to a service job, Mrs. Pine has risen from a service job to wear fancy jewelry and her employer’s dress. Also, as in “The Glow Infernal,” the pages are cream-colored instead of white.

The kid gets something William does not—he gets a surrogate father figure (“we had each other and that was everything, a goddamned gift” (p. 52 panel 10)). He also gets to know that his mother (who disappears) loved him enough to send someone and extract him from…hippiedom, apparently, the perpetual revolution Penny disappeared into.

One note: Johnny calls the kid an “innocent lamb,” which is exactly what Leonard calls himself in contrast to Johnny and Monica (p. 52 panel 4 & p. 8 panel 3). This is also right after Leonard accuses Johnny of “murder[ing] innocent strangers” (panel 1)—perhaps an apt description of Johnny’s actions on page 49, panel 5.

Johnny will tell Monica that Penny believed “the war had ruined [him]. She said [his] soul was poisoned,” a point Penny has made in young Monica’s presence: “I worry you’re going to snap and murder us in your sleep,” she says (p. 63 panel 3 & p. 22 panel 2). “She may have had a point,” Monica muses when she visits him. “There was definitely something off.” In his squalid house, covered in “the grime of madness [,] insane self-published conspiracy tracts sat” (p. 63 panels 3 & 6); as Johnny rants, he rants about “secret societies, the Crusades, the incident, etc.” (p. 64 panel 3).

Excuse me (for in Clowes’s lettering it is ambiguous). I mean The Incident.

Is this story, “The Incident,” Monica’s attempt to determine (i.e. invent) what happened to Johnny? Regardless, we see in the resolutions of Monica’s two stories the working out of two of her desires. William gets to be special; the kid gets a parent.

Success

“Success,” or rather “$u¢¢e$$” (a nod to an old Richie Rich comic logo) purports to give us only “one percent of the story” it’s telling. “It’s pretty action-packed, to be honest,” says Monica, belying once again her chapter-two claim to have led a normal life—but the action seems to involve creating and selling a candle empire, so perhaps with “action-packed” Monica is once again unreliable (p. 53 panel 3).

Monica’s reaction to love (or perhaps potential enfamilification) is, apparently, unsuitable mirth (p. 54 panel 3), a reaction similar to the hospital security guard’s in “The Incident,” the one who laughs at everything “like it was all just some big joke” (p. 52 panel 6). But Monica has always seemed more interested in acquiring a parent than a partner.

We have muted references to previous installments. The car snobbery (Chevy vs. Buick) from page 3, panel 5, reappears in a crack against Toyotas (p. 59 panel 6). Have a look at Liza B., Monica’s best(ish) friend. Her hair looks like a blend of Leonard’s two friends on page 9 (who three pages later are Penny’s friends). Monica’s night on the town with the narcissist Heather parallels Penny’s introduction to Leonard’s friends—except that chiasmically Penny likes Leonard’s friends (whom Leonard calls “head-lice”) while Heather asks Monica “Why do you have such awful friends?” (p. 10 panel 1 & p. 57 panel 7).

“But you?” she goes on. “There’s still a shred of hope” (panel 9).

Monica gets grudging praise from a narcissist, but it’s Heather’s therapist, Dr. Aquarius, who logics out that Monica’s father is a Polarian, granting her special powers. “In some weird way, it kind of made sense” (p. 62 panel 5). This is better than grudging praise! “He kept telling me over and over how lucky I was. ‘Don’t you understand? You have an honest-to-God capital Q Quest!’” (panel 6). This book is of course a record of her quest, first to find her parents and also to find, you know, the Opening (as it were).

One last note from the chapter before things get really weird. Monica relegates her stories to the product of her teenage years, insisting she is no longer able to start one (p. 60 panel 2). Are her stories (provided) really so old? Does she learn to write again? (Answer: yes, as per page 94, panel 2.)

The Opening the Way

Who cares, right? This is what we’re here for, the true Clowesian paranoid weirdness. Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron come hurtling back from 1989.

The situation is reminiscent of the two stories-by-Monica (presumptive) we’ve already encountered—the cult is isolated like the stories’ towns, its compound fallen into disrepair and decay (even neighboring Boondale has disrepair and decay to spare). Monica walks along the fading tire tracks like William walking along the overgrown railroad tracks (p. 71 panel 9 & p. 25 panel 1). The unsuitable laughter we’ve encountered before returns (p. 75 panel 9). Most obviously, the haircuts are William’s haircut and the cult, like his cult, puts on a “show” before making someone bleed.

If I complained before that imagining one’s mother’s postcoital conversation seems a strange thing to imagine…nope, I’m wrong, Monica’s explicitly doing it on page 73, panel 6.

We’re in the genuine action-packed heart of Monica’s life, but the real question here is: Does any of this happen? Are we supposed to believe that Monica infiltrated a cult, failed to gain the approval of V., and then fled into the bosom of a surrogate family she had to abandon in turn, reenacting her own life of serial abandonment from the other side now (…perhaps she initially abandoned her candle company, or even, in her suicide attempt, life itself?)?

V. is a fraud, but when he taught that “reality is a quasi-demonic fabrication” (p. 65 panel 3), was he right…in the sense that his appearance in the book may be a fabrication by someone nicknamed Demonica (a quasi-demonic name)?

Monica herself seems unsure at times. Of her narrative that V. is her father, Monica says, candidly: “This isn’t what happened—I knew that—but it’s the story I settled on to keep my brain from going off the rails” (p. 73 panel 9)—and then she proceeds to act as though the story is true, that V. is certainly her father and she is here to find him. (She maintains the V.-as-father belief until Penny disabuses her of it on p. 97). Does the story she settles on come to consume her until she can no longer tell her fictions from reality? The Way’s whole theology revolves around people’s memories being erased; Monica’s memory has proved untrustworthy time and again.

Monica goes into the Way as a fake, “hoping they’d see [her] as an ‘aurora’” (p. 73 panel 3), seeking to “seem more special” (emphasis on seem; p. 77 panel 4). She ends up insisting that she isn’t (in fact) “just a random follower, but a prime aurora” (p. 85 panel 7). Events in her life “were in no other way explicable” (p. 80 panel 6). In other words, she starts off a doubting interloper and ends up a believer. The second panel of page 80, when Monica refers to herself as “the chosen one,” falls right between these poles—perhaps she believes it, perhaps she merely knows that others believe it. This ambiguity will evaporate as the “wedding” (as she calls it on page 81, panel 2) approaches.

The Way offers Monica some things she clearly wants: family, for one. Thinking of the “thwarted…woman-child” Alice, Monica muses that had she been raised in the cult, “think how close we would have been; closer than sisters. That would have been something” (p.76 panels 7 & 8). Note how similar this sentiment is to the last panel of “The Incident”—but, again, Monica has always wanted a parent more than a sibling.

But it also offers her the opportunity to be special. Every cult offers its member the opportunity to be special, of course, but Monica is special even in the context of the cult. Is she not the chosen one? If Monica is ever going to be the focal center of all human existence, this is her chance.

The last time Monica was supposed to be part of a wedding, the bride bolted. Although the events leading up to this wedding are presumably no less hallucinatory (“more like a dream or one of my stories than real life,” remember, Monica called it the first time), at least this “marriage of fourteen bodies into one” (p. 83 panel 1) makes it to the end of the ceremony. And then…

In her postnuptial interview with V., Monica bollixes her chance to be chosen (and presumably to be “born anew,” whatever that entails) (p. 83 panel 5). While running a dialogue with V., she breaks character, claims he is her father, and tells him “the whole story from the beginning” (p. 85 panel 4). In this way she (apparently; we’re not given too much detail) tries to split the difference between her two desires, asking for a father (and news of her mother) while still operating within a Way context that leaves her special (or “focal”). Clearly it doesn’t work.

I can see an argument against, but am inclined to believe that Monica does indeed fall among the Way, meets V., and escapes. In later years she refers to having joined a cult, and apparently tells her therapist about it, suggesting that there’s at least a kernel of truth here (p. 95 panel 6). Perhaps she made some stuff up to cover the embarrassing truth that she just straight up and unironically joined a cult? Perhaps some of the details of her Way time are clouded by the brainfog that settles upon cult members? But surely the broad strokes are there. Believing in Lux and the prime auroraship? That was all “total Stockholm syndrome” (p. 87 panel 1).

But Monica is still left with her capital-Q quest; and a clue; and two more chapters, which will presumably tie everything together.

Krugg

Well, not this chapter. Note that Krugg, if the title is to be believed, has one more g in his name than in his previous appearances (and in Monica’s futile google searches (p. 11 panel 7)).

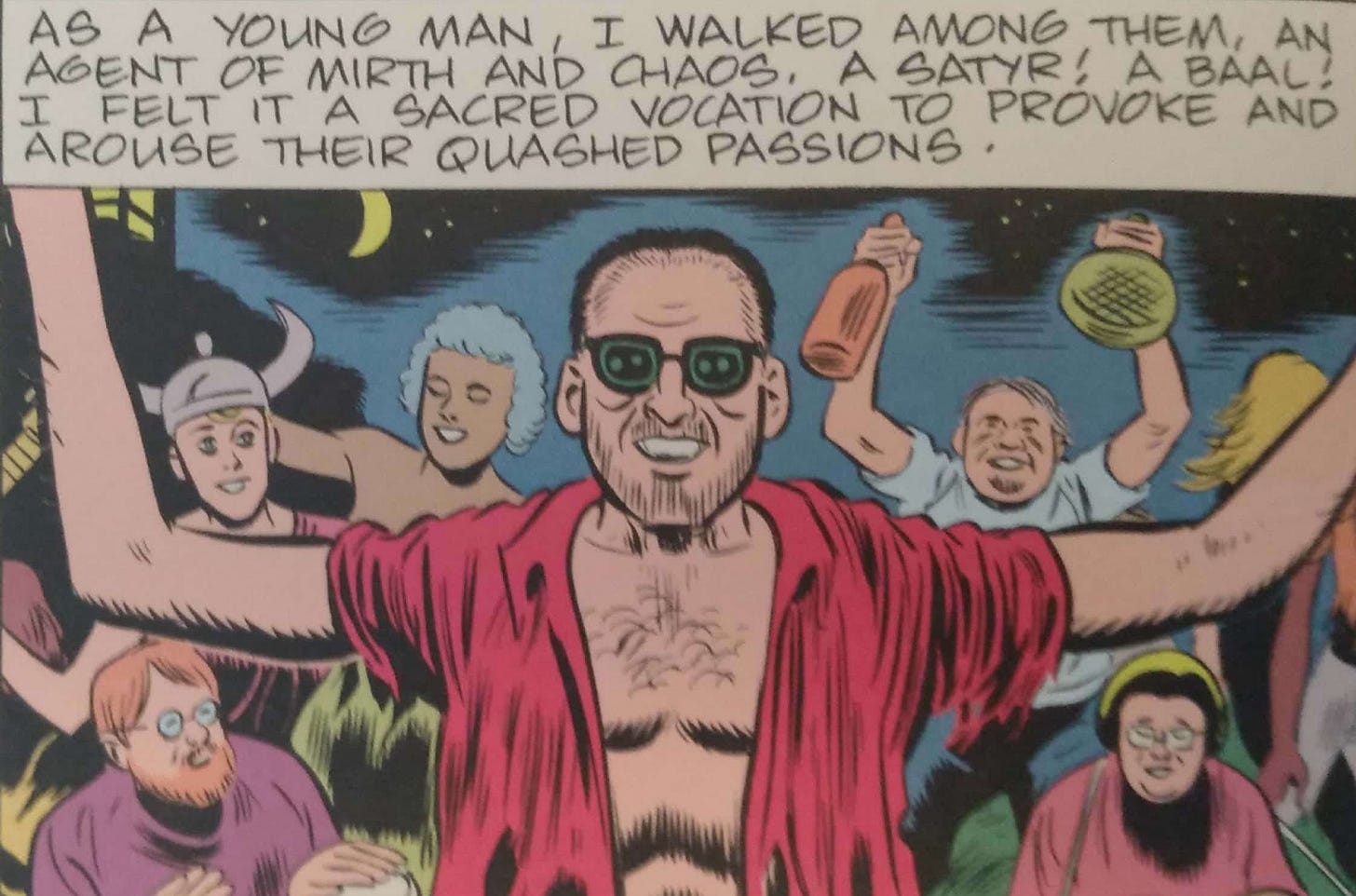

But of course he doesn’t, because this is another Monica story. The cream-colored paper is a tell by now, as is the theme of absent children in search of reunion. Krugg, though is (like V.) no father but an explicit fraud. (The silhouette of the would-be daughter on page 91, panel 7, looks like Monica’s, still seeking her father.) As always, he stands in direct opposition to Johnny. Where Johnny is haunted by his past, Krugg revels in his (p. 90 panel 4). Johnny’s isolation looks like failure, but Krugg’s is a triumph. Even their messy homes—Johnny’s evokes “despair,” but for Krugg, that root beer stain on the wall is as important as the color of the sky (p. 89 panel 3)!

Another “story tell”: the reappearance of Mrs. Van Thorne from “The Glow Infernal” (p. 92 panel 1). This is a fiction. One-g Krug is the man; Krugg is Monica’s fictional character.

Krugg, like Monica, plays it somewhat coy about reality. “My rambles of the mind, be they real (as I contend) or imagined etc.,” he says, a very Monican phrase—doubtless because she wrote it (p. 63 panel 4 & p. 92 panel 3).

The key to Krugg (and therefore to “Krugg”) is Krugg’s boundless self-importance. Like Monica, he “possess[es] abilities for which there are no logical explanations (p. 90 panel 1 and cf. p. 80 panel 6). His “debauched crusade” apparently transformed “the entire culture [into] a vast legion of Kruggs,” a triumph he has perversely turned away from (p. 90 panel 6).

It goes without saying that his monolog (like all Monica’s fictions) would also fit in fine as an Eightball short. “I’m looking cold-eyed toward the infinite chasm within. I suggest you do the same before it’s too late,” is one of the most Clowesian statements in existence, but Krugg could easily also narrate “I Hate You Deeply” or “Cool Your Jets” or “MCMLXVI.”

Doomsday

Why “Doomsday” and not “Apocalypse” or “Armageddon” or “Eschaton” or whatever?

I haven’t really harped much on the comic-bookness of Monica, the panorama of comic genres, Krugg-as-Cryptkeeper, etc., but perhaps it’s salient that in comics Doomsday killed Superman (while Apocalypse has only managed to create a gimmicky crossover). More likely, though, doomsday is one-half of doomsday cult. Monica’s thoughts ever stray to her greatest chance to have been the centerpoint of human history. (Her “‘princess in disguise’ delusion” Dr. Joy calls it (p. 96 panel 4).)

But she has become in may ways the opposite of her previous persona(e). Back in “Demonica” she noted (perhaps inaccurately, as we have seen) the contempt lake people had for outsiders; a local herself now she calls tourists “invaders” or “occupiers.” She has become a hard-headed rationalist “committed to sober rational truth over symbolic coping fantasies,” debunking UFOs…not to anyone who would listen, but just to herself as she ambles by a stream (p. 95 panels 3 & 4). Although religion has been a steady undercurrent through the book (starting with the discussion in the first chapter—but then, there are no atheists in the foxholes), Monica has settled on a life that is “godless”—as well as “sexless” (p. 100 panel 2 & p. 93 panel 1).* At least she is, at last, writing again (catch her in the act, writing longhand while watching Cannon: p. 98 panel 2).

This life of relative stability is, once again, a post-Penny occurrence, for Penny is now dead. Monica had earlier traced the clues to her mother, who was paranoid, living in squalor, her table littered with pill bottles, her mantel littered with candles (!!), and her floor littered with garbage, in a house not her own. We learn she was the widow of…Butch?

Butch, from chapter one? He who accurately predicted “a wound in the soil” but inaccurately predicted, apparently, that he would get no “prom queen pussy” (p. 5 panels 8 & 3). What are we to make of that?

Of course things get much stranger. Although Monica has been drawn into a kind of family situation in the past (paternal Ike), she sports a “fear of relationships” glibly diagnosed by Dr. Joy (who also seems to be diagnosing the whole necrophony incident as merely a “serious episode”) (p. 95 panels 6 & 4) and now threatened by the arrival of (Clowes lookalike) Stan. Stan comes clad in a panoply of coincidences none of which nevertheless strain credulity. These kinds of things happen.

Is it in search of a way to torpedo the promise of a relationship that Monica heads off to find her birth father? When Penny was in danger of getting married, she leapt into the bosom of a cult; seeking the absent father is comparatively sober (at least at first). Monica leaves for the visit apparently bursting with somewhat paranoid promise (“Had Dr. Joy been talking about something deeper etc.”) (p. 102 panel 8). But Steve had led (as Monica had once threatened to lead in the very same words) “a normal life” (p. 24 panel 8 & p. 103 panel 3). She parts from him feeling nothing and yet fantasizing about being murdered Psycho-style, surely a whirlwind of emotion and not-emotion; Monica says, “It’s quite a blow to discover after a lifetime of fairy-tale fantasies that you’re not really special” (p. 104 panel 2).

Monica adds that Penny had “allowed me to invent my own provenance” (p. 104 panel 3). How much is Monica inventing?

And now. For the final time a lost soul returns to the youthful hometown seeking a parent only to find everything different. This time the entrance is easy (“the main road was a bit wider”) and the place is not a dump (“bland, but it could be worse”) (p. 104 panels 5 & 6). Monica’s bought a shovel, and the story will end, as it began, in a hole.

When Monica heard her grandfather, it was one electronic device (Walkman) that led to the important one (radio); now it is one excavation (by a cypress) that leads to another excavation (near an oak). And the second excavation ends all things.

What are we to make of that ending? Page 107 seems to embody Butch’s prophesied “rain of fire and blood” (p. 5 panel 8). And just as the front endpapers gave us the earth’s first days, the back endpapers give us the last days, as everything bad happens at once. It’s an almost parodic (and, just to be comic-booky for a moment, Wolvertonian) overload of disasters: tidal waves, fire, earthquakes, lightning, large rocks falling from the sky, demon bats, an airplane crash (due to large rocks and demon bats?), buildings are literally melting, so is flesh, pestilence, and humans are monsters and fall upon each other mercilessly even as they are being swallowed into pits, while a mere mushroom cloud is almost lost in the background. Maybe something’s happening to the sun, too (or is this Krypton??? that would explain so much???).

In the foreground, a lone candle burns, somewhat tranquilly; but it is down to a stub, and perhaps cannot last long. Monica’s Candles, I guess, but I don’t know what to go with that. Of course, Monica’s Candles has (have?) already been consumed twice, once by fire (and hippie radicals?), once by corporate takeover (and therefore capitalism?—is this the axis we should be looking for answers along?).

Are those three rotted oaks positioned like the dancing Daughters of the Hollow Cypress (p. 108 panel 1 & p. 29 panel 1), or are there only so many ways to position three objects (and the Daughters are clearly doing a Three Graces thing)? Certainly everything at the ending of the book feels similar (tonally) to the ending of “The Glow Infernal.” (“Several voices speaking all different languages” (p. 106 panel 3) may well come from the multifaced monster on page 34; once again terror comes from the pit.) Is Monica planning on ending up as the focal center of all human existence after she digs?

Well, of course she is. What else does she have to hope for? Her dream of being the daughter of first V. and then anyone interesting or special has been shattered, and if she cannot be special and important and save the world, perhaps she can destroy it. Monica’s character Krugg’s ambiguous take on his legacy (turning society in a 24-hour bacchanal) is telling. To save society we had to destroy it, as Finley (one of the most minor of characters in the book) might have said.

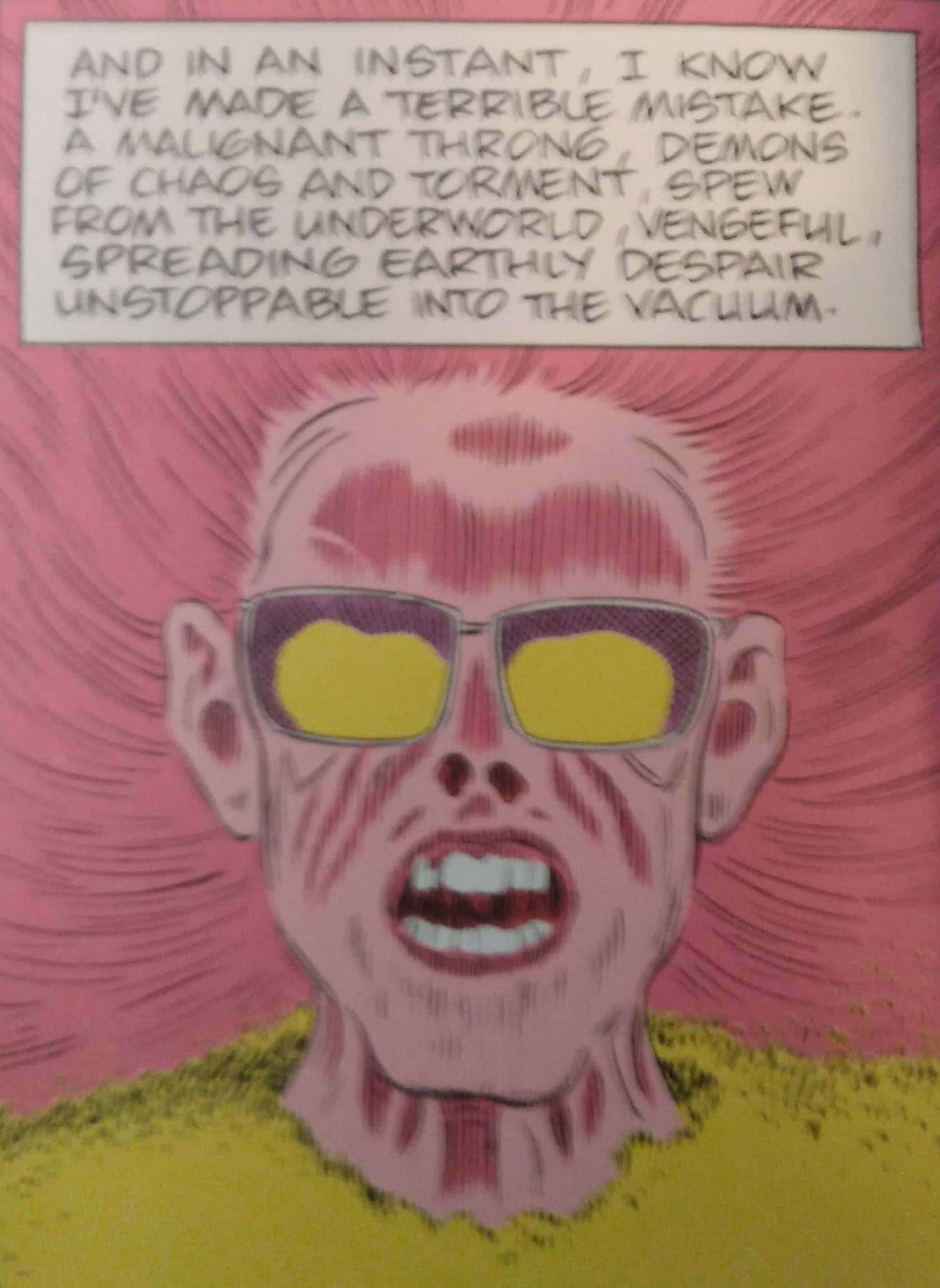

Krugg is an “agent of…chaos” (perh. N.B.: “of mirth and chaos”; Monica is disintegrated by “demons of chaos” (“…and torment,” t.b.f.) (p. 90 panel 4 & p. 106 panel 8—the final panel in the book proper).

It is, of course, possible that Monica is special, that her whole life has been choreographed by some vengeful ancient god who has step by step led her (finally by the coincidental S(a)tan and the overly banal Steve) to this one part of the woods, to dig and dig and doom the earth. Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn. Thereby: Monica is the story of the Earth, or the universe, with the first jillion years skimmed over quickly in five pages and the last half-century examined in more detail.

But I think it is more likely that Monica is simply desperately desiring to be special. Conventional success didn’t make her feel special. A cult came close, didn’t it? but not close enough. Under stress (such as after her grandparents’ deaths; or after a suicide attempt following her grandparents’ deaths) she’s more than willing to indulge in invention. This book is the story of Monica’s gradual disillusionment with her own specialness, and of the “Grand Guignol fabrication” (Krugg’s term: p. 89 panel 1) she “settled on to keep [her] brain from going off the rails” (as we quoted before: p. 73 panel 9). The nice thing about thinking if I’m not special I’ll just destroy the world is that if you can destroy the world it turns out you were special all along. Check mate, reality! Monica at last belongs beside Jesus, Shakespeare, [Hitler], and Little Richard as one of the key stepping stones of history.

Ending a story with a character putting a bullet through their head feels like such a Daniel Clowes thing to do that I was surprised, digging through my back issues, to find only one example (“Cool Your Jets”—and maybe Stew doesn’t pull the trigger; does Ernie do it in an issue of Lloyd Llewellyn?). It’s possible to read the ending here as Monica’s suicide, but I think it’s more likely a temporary fantasy while she figures out what to do with Stan, her own banality, and the end of all parental mystery.

Or maybe she goes crazy. Or maybe her face melts off and it’s demon bat time.

Oh yeah…and the back cover

I don’t even know where to begin here. The back cover appears to depict a tattered old Johnny with a shovel looking at three of Monica’s stories: action-Jonny with gun from “The Incident”; the Daughters of the Hollow Cypress between two cypresses of undetermined hollowness and above that fatal cave from “The Glow Infernal”; and Krugg as a satyr (one of his self-identifications: p. 90 panel 3) from “Krugg” (standing on…three rocks!). Who’s the sinister red-robed figure? Is that a crumpled red robe in the foreground of V.’s apartment on page 65, panel 6, V.’s red-robed arm on page 66, panel 4? I don’t know.

The Big Bang/sun in the upper right is no more explicable here than on the front cover. It is clearly night (so no sun, right?), and anyway the main light source is ostentatiously coming from the left, opposite this mysterious sunburst.

Is Johnny with a shovel some clue that cleverly suggest he, like Botkin from Pale Fire, is the true author of the Monica-penned stories and perhaps the entire book? Why is his shirt ripped? I’m lost here.

Conclusion, chapter by chapter

Here are my working hypotheses, with approximate page colors based on my own fallible eyes:

Foxhole (off-white pages): With Butch and Johnny tidily serving as two (potential) husbands for Penny, this has to be a fiction written by Monica.

Pretty Penny (bright white pages): This is a reconstruction by Monica, but it mostly more-or-less happens (with the exception of a couple of panels of acid trips and things).

The Glow Infernal (cream pages): This is a story by Monica.

Demonica (off-white pages): This is mostly Monica’s post-coma hallucinatory memory, although presumably some parts are accurate.

The Incident (cream pages): This is a story by Monica.

Success (off-white pages): This happened.

The Opening the Way (white pages): This happened, probably more-or-less as depicted.

Krugg (cream pages): This is a story by Monica.

Doomsday (white pages): This mostly actually happens, but the end is Monica’s fantasy.

Therefore

Here’s what happens. Earth starts up and time marches on. Eventually, in the 1960s, a woman named Penny (chapter 2) leaves her solider-boy to live a counterculture life, birthing an acidhead’s daughter whom she drags through a “freaky” existence until she leaves said soldier boy (a second time) at the altar and disappears into a cult (which she then leaves, to move to Texas and marry another vet). The daughter, Monica, is raised by grandparents, who eventually die (4). Stripped again of any parental support, at a low point in her life, Monica (perhaps after a bad experience with a visiting Nathan?) intentionally crashes her car. Later she will pretend or hallucinate that the whole incident had been precipitated by a necrophonic experience.

A coma. After she recovers (6), our hero starts a candle company (inspired by her mother’s entrepreneurial endeavor), makes a heap of money, and leaves it to go on a semi-spiritual journey in search of that very mother. Somewhere along the line, Monica (like most of us) has developed a pathological (?) need to be “special”—epoch-shatteringly special, I mean. Anyway, clues lead her to attempt to infiltrate the cult (7), which she later flees (probably in a moment of genuine peril) after failing to cement her special status therein. Her mother, finally found, proves a disappointment (9).

Monica settles into a pleasant existence (still 9) until the appearance of a potential beau leads her to seek out her final hope for a special Polarian parentage. The reult: overwhelming banality. Monica retreats to her earlier chapter-4 fantasy, and becomes at last, in her mind at least, “the turning point and vortex of so-called world history” (to quote Nietzsche). In fact, she imagines (unwittingly) destroying the world, once and for all. The end (but not for the world, nor for Monica, who is still left with a life to address, perhaps).

That more or less holds together. And yet…why, if “Foxhole” is but Monica’s story, are the pages not cream? What do the other colors mean? Are they actual clues or just some printing artifact? Is there really a difference between bright white and white pages, or were my hands dirty when I read some chapters? Why are the “fictional” chapters consistently odd until chapter 7, after which they’re even? Would it have killed you to hack out a fiction to place between 6 & 7, Daniel Clowes? Or is this, too, a clue (that I have misunderstood)?

There are a hundred more open questions like this one. Is it weird to have characters named Van Aaden and Van Thorne in the same book? Are all the big-haired blonde older ladies supposed to resemble Sonny Boy, or is that my own brain problem? I’m sure there are dozens of extra parallels between chapters I have missed, as well. I’m doing my best here!

It’s just a prolegomenon, people. We’ve got miles to go.

*A footnote: Stan, not Monica, says he is godless, but Monica says in the same panel that they “both felt” this way, so I used it.

WOW! I just finished reading Monica and am so impressed that you derived all this meaning out of the book. Beautiful work! Your passion is felt :)

Excellent writeup. I think you're right on the overall structure: it's the story of Monica's attempts to create some kind of "special" myth for herself. I think the colors tie right in with that: the darker the color, the greater the degree of fabrication being employed by Monica.

Ordering by brightness, we get:

LEVEL 0 (bright white)

Pretty Penny: This is partly a reconstruction by Monica, but there seems to be no self-glorifying embellishment here--no intentional distortion and a portrayal of what may be Monica's original sin of letting her mom read the Opening pamphlet.

LEVEL 1 (white)

The Opening/The Way: True in large part, though containing an idealized fantasy of her mom meeting V. and her own idealization of herself being an Aurora.

Doomsday: True in large part, but distortion in the final scene at the least, and possibly elsewhere.

LEVEL 2 (off-white)

Demonica: obvious fantasy with Monica's grandfather and the radio, and general reality confusion.

Success: seemingly realistic but see below...

LEVEL 3 (off-off-white)

Foxhole: Monica's fantasy about two real people, ennobling Johnny and prophesizing Monica's fate. Maybe not an actual written story.

LEVEL 4 (cream--all stories written during the Doomsday period)

Glow Infernal: story by Monica

Incident: story by Monica

Krugg: story by Monica

(I could be wrong, but I think "The Opening/The Way" is a slightly different shade from "Doomsday," but I couldn't tell you which is lighter. "Success" and "Demonica" also seem slightly different, with "Success" maybe being darker. But they're close enough that I'm going to group them.)

The only one that feels really out of place is Success, which seems far more grounded than Demonica despite being at least roughly the same color. However: Monica's rags-to-riches-to-rags story seems quite convenient, glosses over big chunks of her life, and contains many self-glorifying moments like being interviewed, Aquarias calling her special, and Heather's uncanny prophecies. How much of this actually happened? Or perhaps it reflects her own loss of reality as she adopts her fake "success" persona and finds that it doesn't make her special enough. Aquarias goes from being a con-man to a prophet in two panels, so even if this all actually happened, Monica isn't especially in touch with reality here.