(I decided to share some short stories I wrote in my youth. Or, like, at least this one.)

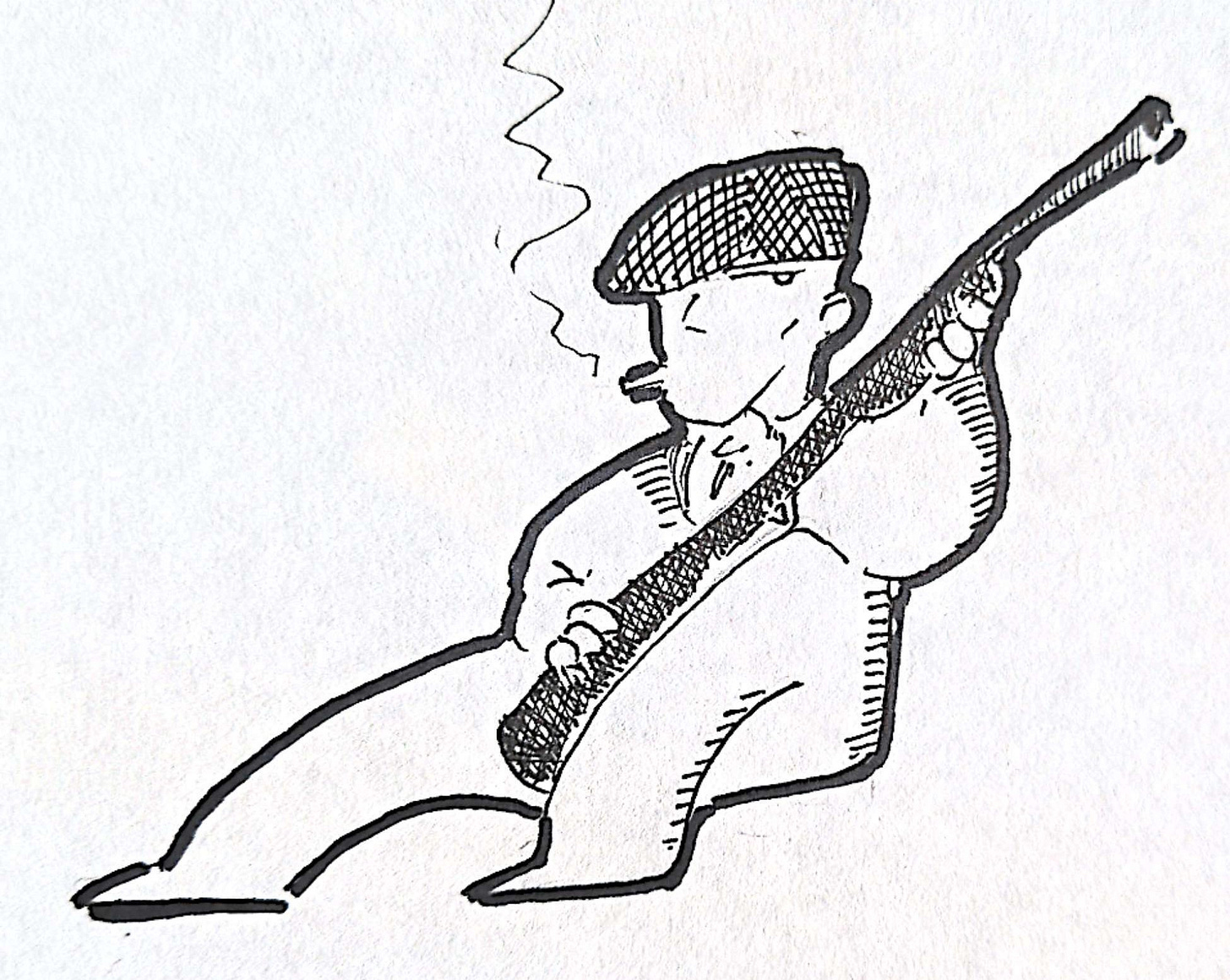

A man impales a cork on a metal skewer, holds it in the fire. Flames lick the metal, sooting it, blackening the cork. When the cork has cooled, he rubs it on his face, his hands, the shiny parts of his rifle, the medals on his uniform. He seems particularly disgruntled about having to soil his medals that way, and his rifle, which shone before as brightly as a newly minted penny that has never changed hands.

I had things somewhat easier. My rifle was an old, scavenged model, made from wood and pig iron, that only shone when wet. Medals I lacked, although I had received two patches, one for being conscripted and one for not deserting, which were waiting in my breast pocket to be sewn on. My hands and face were already a uniform gray, what with the caked-on mud—in fact, my whole body was gray, save for a pink ring chafed clean by the waistband of my jockeys. There was no moon. “Come on,” the blackened man said, dropping the cork into a puddle in the bottom of the trench.

We slipped out onto the field, rifles slung over our shoulders and clipped to our belts, so they wouldn’t come sliding over our heads as we crawled. This clip made it impossible to ready your rifle quickly, but that hardly mattered, as we were under strictest orders not to fire them at any cost. I had a box of grenades, which I pushed ahead of me with my hands while I snaked forward on knees and elbows. I could hear an occasional shot from the Corolonian line, followed by panicked chastisements. “Show some hustle, soldier,” the corked-up officer snapped. I followed him. He appeared to have sat in some chalk dust, or dry clay, before going over the top, for the seat of his trousers was dusted white. I tried to think of where in the trenches the clay could possibly be dry. I followed his bright buttocks winking in the dim starlight as we crawled. We were a good thousand yards from the Corolonian trenches. I saw the white buttocks in front of me disappear suddenly; there was a splash, and some cursing. “Mind the crater,” the officer called, but I had already crept closer to investigate, and the box I was pushing had tipped in over the lip. I could hear clattering as the grenades tumbled out, and the soggy thumps.

“Mind the bombs,” I called, and the officer was out of the crater in a flash, racing back to our lines. “Abort mission! Abort!” he screamed although there was no reason to believe those grenades could be set off by anything other than random chance.

“Partial success,” he told everyone when we returned. “The bombs are much closer to the enemy lines than before.”

“You were hardly gone five minutes,” PFC Effingham said. The officer, what was his name? got into his truck and was driven back inland, away from the front, ignoring Effingham.

That Effingham, he was my only real friend in the trenches. He had given me his helmet—helmets were in short supply—when I first arrived at the front; Effingham hated helmets. Every time he got issued one he’d give it to some other sap who had no helmet, and go report it lost or missing. Then they’d send a new one, he’d give it away, report, and another issue. I don’t know why he didn’t just keep his mouth shut about losing the helmet, but mine is not to reason why, and anyway, Effingham way outranked me.

“Boy,” he said to me that day. “What happened to those bombs?” Boy was not an insulting term. My name is Anthony Boy.

“They’re in a crater, Mr. Effingham,” I said. “They’re wet.”

“Good, good. Good enough. Well, you should come and meet the cracksman.”

The cracksman? “Like Raffles?” I asked.

“Come and see. He just arrived while you were gone, and I haven’t spoken with him yet myself.”

The cracksman turned out to be a tall, slender Frenchman with a violin case. He was wearing black silk civvies, very dapper. He was shaking everyone’s hand. You could tell by the way he looked around, and by the way he didn’t have scurvy, that he wasn’t used to a life of mud and lice and filth; but he hardly acted squeamish about it, either.

Effingham went up and shook his hand. “Zugazagoitia,” the cracksman introduced himself.

And: “Here, man,” he said to Effingham, “what’s become of your helmet?

“I lost it,” Effingham preened.

“Well you can have mine; they issued one with the uniform, but I really have no use for either.”

Effingham accepted it with unconcealed pain. There were hardly any helmetless men left in our battalion. He said, “And this here is Anthony Boy.”

We shook. “Are you really a cracksman?” I asked.

“A crack shot, Boy; a crack shot.” Zugazagoitia then “bummed a fag,” and “split for mess.”

“But they can’t let him shoot,” I whispered to Effingham afterwards. “That’s against orders.”

“I’m sure there are special provisions for cracksmen,” said Effingham.

*

Zugazagoitia had been all over the front, and oh! how he told us stories. Like how at other places you didn’t crawl around no man’s land, you walked upright. That was because machine guns were set up to shoot just an inch above the ground, in the hopes of catching someone peeking their head out of the trench. So you walked, because then machine guns would hit your feet, instead of your head. After your got hit in the feet you might then tumble down, to where the bullets hit your head; but it was important to do things in the correct order.

Of course, we had no machine guns around here; this was a pretty crappy area no one cared about. All our rifles were fifty years old, too (except the officers’, which were shiny brand new, but just mock-ups, toys) and exploded in your face about one time in six if you tried to fire them. Of course, at a thousand yards you couldn’t hit any Corolonians, either, anyway.

And that was why, Effingham explained to Zugazagoitia next morning, we weren’t supposed to shoot at all. At first, when the whole thing began, everybody’d been blasting away at each other, and the only casualties came from exploding rifles, never from enemy bullets. So some egghead reasoned out that if the Corolonians were just as bad off as we were equipment-wise (and they were), all we had to do was stop firing, and in a few days the Corolonians would have blown themselves to pieces trying to shoot us. Unfortunately, they caught on, and stopped firing too (unless their eggheads had them stop firing first, and we caught on). Now the only people who fired were simpletons and greenhorns, and evolution was weeding them out.

“We’re in the process of moving our bombs over near the Corolonian line,” Effingham added. “Most of these bombs wouldn’t go off if you used them for fuel, of course, but them what do blow up tend to blow at random, so it’s better we get them away from us.”

“Do you play violin, Mr. Zugazagoitia?” I asked.

“No, my chipper Boy,” Mr. Zugazagoitia said, adjusting his rakish cravat. “That is simply the tool of my trade.”

“Your lockpicks?”

“Come, gather round,” Zugazagoitia said. “I’ll show you.” He opened the violin case with a snap, and removed from its velvet cushioning three silver rods. He screwed these together like a “billiards champ,” which is army slang for a plumber. He kept removing pieces from his case and attaching them to his contraption: a stock, a trigger, telescopic sights, etc.

“What is it?” I asked.

Zugazagoitia held it up and everyone sighed. It was a beaut of a rifle, extra long, shiny, and new.

“You’re not planning on firing that, then?” Effingham asked.

But Zugazagoitia already had the rifled up to his shoulder. “You see that man doing callisthenics there?” he said.

“No,” said everyone except Blair, who had a spyglass.

“Yes,” said Blair.

“And that other man, some rods to his left?”

“No.”

“Yes,” said Blair.

Zugazagoitia fired. We all dove for cover. “He’s mad,” we said.

Zugazagoitia fired again.

*

This is what our moles and spies told us was being said at the Corolonian lines:

Corolonians (all): Ha ha! Stupid Palamans! Firing again!

A Corolonian: Oh my! Scotty appears to have passed out from excess callisthenics.

Another: Touch of sun, may be. He must have hit his head on a rock—there looks to be quite a spot of blood.

Yet another: Say! Rudy’s tuckered out, too.

Again: And also hit a rock I dare say.

Corolonians (all): Ha ha! Stupid Palamans! Still firing.

And another: Ah! Sergeant’s come down all heat stroked, it seems.

Still another: And Meyer.

Etc.

*

Well, there was quite a commotion, I bet, when the Corolonians found out we were killing them with gunfire. Like ignorant natives, I bet, when they first discovered, with superstitious dread, the power of the “thunder-sticks” so-called. At least that’s what Effingham says it was like. And there was quite a commotion in the trench once we realized that Zugazagoitia’s rifle wasn’t going to blow up. And Blair, he managed to convince us that the Corolonians were actually getting shot, and that made us as happy as shooting at ignorant natives, it did. We jumped up and down. We yelled, “We’re number one!” and “In your face!” We drank quite a bit. And the whole time Zugazagoitia was just crouching there, picking them off one by one until all the Corolonians (he told us) were huddled in their trenches, not daring to show a hair on their miserable heads.

“Here’s to Zugazagoitia,” we said, “the finest cracksman of them all.”

“I’m a crack shot, actually,” he said but accepted our toast.

That afternoon we all grabbed a crate of grenades and marched, calm as can be, out of the trench, across no man’s land, and right up to a few yards from the enemy line, where we deposited the whole shebang. Any Corolonian git who stuck his head up to shoot at us, or, since they were under orders not to shoot, lob a rock, got popped by Zugazagoitia, who was sitting half a mile back scanning the Corolonian line. We laughed as we marched back, and suffered only one casualty, when Swanstrom stepped on a nail. Actually, it was pretty bad, and we had to hustle him off to hospital, and he sent us a postcard later saying how the leg had to come off, in the end, so that was sad. But at the time it was a great victory. And the next day was a great victory, too, with Zugazagoitia standing watch and shooting bad guys while we egged him on and on.

“Corolonians suck!” we screamed. “Hey you! Yeah you, Corolonian, can you hear me? You suck!”

And Zugazagoitia fired and fired. Of course, he didn’t get as many as he did the first day, because now no one did calisthenics right out in the open. They hid and they skulked and they crouched in their trenches, but every once in a while one would get careless and stick his head up and BANG was the end of him. It almost got boring.

“Mr. Zugazagoitia,” Effingham said to him one day. “The boys were all wondering if maybe you could do some stunt shooting. For morale purposes.”

“Stunt shooting?”

“Yes sir, you know, like shooting standing on your head, or blindfolded, or while treading water in a big barrel.”

“At what would I be ‘stunt-shooting’?” asked Zugazagoitia.

“Oh, Corolonians, of course. We thought it would be real demoralizing for them if they died and you were doing all sorts of capers at the same time.”

“You know, I can smoke two cigarettes at once while firing…” said Zugazagoitia.

“We have the barrel all ready,” said Effingham.

That was how Zugazagoitia ended up killing three Corolonians standing on his head, two more while eating an apple (he could have done more, he pointed out, but he’d finished the apple already), six one-handed (including one Corolonian who was one-handed himself, quite the coup for Zugazagoitia), and one while he treaded in an enormous barrel full of rain water. He never managed to hit anyone while blindfolded, and the Corolonians razzed us some for that, but overall we got the better of them at every turn, what with so many of their people dying and all.

“These thoughts keep me warm at night,” PFC Effingham said to me one lazy afternoon as we sat dangling out legs in our trench. It was a pleasant day, sunny; there was a “softball” match going, and the shouts from players and crack of the bat mingled with the crack crack crack of Zugazagoitia’s rifle. “The thoughts,” Effingham continued, “of the absolute hell the Corolonians must be going through. Huddled in those dank muddy trenches like animals, stooped over Neanderthal-style when they walk—and you know how muddy those damned things get. And always afraid, Boy, that’s how the Corolonians are most like animals, they’re always afraid, afraid they could be killed at any minute by a tiny piece of metal moving too fast to see, too fast to hear. Hee hee, and we got them, Boy, we got them bastards good.”

“Yeah,” I said, “we’re number one.” I was half listening to the “softball” players, arguing about what the bases were again.

Crack, went Zugazagoitia’s rifle, crack crack.

Oh, Zugazagoitia was quite the darling of our “squadron” (or whatever). We brought him his meals, we gave him our blankets and cigarettes and chocolates and the snapshots our girls sent us from home. Effingham tried to give him his helmet, but the cracksman politely demurred.

“For he’s a jolly good fellow,” we sang.

“I’m touched,” said Zugazagoitia.

When it rained we held umbrellas over him, and Blair and a few others started building him a little shack with an open front, for Zugazagoitia’s use and his use alone; unless we were invited in, of course.

The rest of us, when we weren’t pampering our cracksman, would go fishing in the rain-filled craters, or work on our tans, or monitor the wireless for jazzy tunes. That’s what Effingham was doing, playing with the wireless, I mean, when he heard an official-sounding voice repeating, “723486, 723486.”

“What does 723486 mean, do you suppose?” asked Effingham later that day, while we were taking turns lighting Zugazagoitia’s cigarettes. Zugazagoitia was engaged in the particularly demoralizing stunt of facing backwards holding a mirror and firing over his shoulder, which is why he had no hands left over to light cigarettes with.

“723486?” he said.

“Yes, sir. I heard it on the wireless,” said Effingham.

Zugazagoitia turned around, knelt, started to disassemble his rifle. I noticed how shiny it was still, and new looking. We would all have liked to polish it; but no one touched the rifle except the cracksman, Zugazagoitia insisted. He removed the sights, the stock, the trigger, and unscrewed the long barrel, fitting each piece into its slot in the violin case. “I’m sorry, boys, but that’s the code that means I must go. I’m being recalled.”

“Are you sure you have to go?” we asked.

“Perhaps I misremembered the numbers,” Effingham suggested.

“No, my friends, I’ll be needed elsewhere, I suppose.”

“Is that what 723486 means, Mr. Zugazagoitia? That you’re needed elsewhere?” I asked.

“Not quite, my dear boy, but effectively so. It literally means that a…a ‘cracksman’ (to use your vernacular) has been dispatched by the Corolonians to this theater. Wouldn’t do to have two around, now, would it? We’d just end up shooting each other. Bally silly, that would be.”

A truck swung by a few minutes later. Zugazagoitia stood next to it, distributing to their rightful owners some of the sweetheart snapshots we’d given him. Then he pulled himself up in the passenger seat and waved. Effingham tossed his helmet into the back of the truck as it roared away. “There goes a damn fine shot,” said Effingham, who the next day passed out from sunstroke and hit his head on a rock, while the Corolonians cheered.