The opposite of alternate history

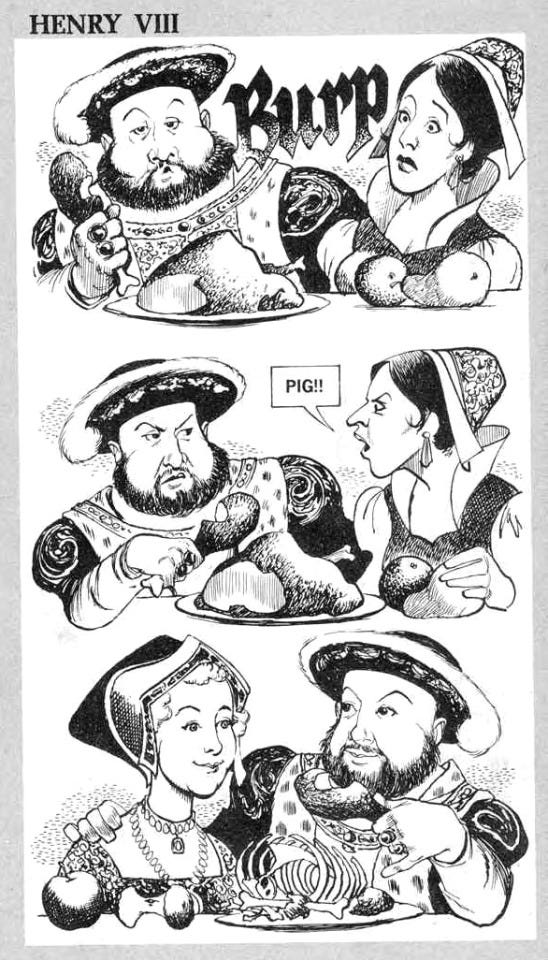

What if Henry VIII decapitated two wives…oops, he did!

I got married to the widow next door.

She’s been married seven times before.

•Herman’s Hermits (1965).

To craft an alternate history is generally to indulge in flights of fancy, and outside of the most banal observations (if Archduke Ferdinand had dodged the bullet, WWI would not have happened in 1914) most extrapolations are almost certainly wrong. But maybe it’s worth taking a moment to see how an event really can ripple through the centuries in an unforeseen fashion.

When Henry VIII executed Anne Boleyn in 1536, he may have seen all sorts of complications arising from the act, but he probably could not have guessed that as a consequence 178 years later a German would be siting on the English throne. This is hardly a secret or a revelation, and probably you already know what happened, but I thought it might be fun to go over the steps. Again, these are not occult steps. Presumably many an Englishman in 1714 who turned to his countryman and said, “Why are we ruled by a German again?” received the answer, “Because Henry VIII killed Anne Boleyn.”

It goes like this: Henry kills Anne for various reasons perhaps including incest and witchcraft but probably because she bore no son and only Elizabeth. Of course, in a previous installment Henry had also alienated himself from the pope and started England on the road to Protestantism. When Henry dies, after some rather violent backing and forthing, Elizabeth takes the throne. It’s a good time. The Spanish Armada sinks, Drake circumnavigates the globe without being killed by Filipinos (unlike Magellan), Englishmen remember how to write poetry, and there’s an all-around golden age.

Centuries past they called our land

“Merry,” as though merriest,

Queen Elizabeth named “good”

Just as though she were the best…

But as golden ages will, it passes, and Elizabeth dies, singularly without heir.

It’s not like English monarchs hadn’t died without heirs before. Richard I had no legitimate children, Richard II had no children at all, and Richard III’s only legitimate child died before he did. The Stuarts would later make a career of failing to reproduce. But Elizabeth had no children as a matter of policy, which I think is unique in the annals of the English monarchy. You can argue about why she chose this route—a desire to keep power in her own hands, a mourning over a dead love, a fear of childbirth—but remember that Elizabeth first declared “I will never marry” when she was eight, before she had power, a dead love, or the possibility of pregnancy. What she did have was a dead mother, and a father who was about to kill again. Elizabeth’s father killed his wives and Elizabeth never married, and you don’t need to be a Viennese psychologist to connect those dots.

As Elizabeth had no children and no surviving siblings, she had arranged for James Stuart, a moderately distant cousin, to land on the throne, which would have been fine had he not already been king of Scotland. The problem was that royal custom in Scotland differed from royal custom in England, and Scottish kings were used to getting away with things.

Macaulay writes that although we may think of Henry, Elizabeth, et al. as being somewhat overbearing in their reigns, “it was, however, impossible for the Tudors to carry oppression beyond a certain point: for they had no armed force, and they were surrounded by an armed people.” That is to say, the monarchs reigned with the tacit approval of the population of England, and they were cautious enough to keep on its good sides. Scottish kings, however, played their hand with a little more abandon. King James’ father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, all Scottish kings, had all died on the battlefield. His great-great grandfather, also a king, had been assassinated. No Scottish king had died a natural death since 1406, when Robert II had died of heartbreak.

Furthermore, Scotland had a history of more autocratic monarchs. The Stuarts brought to England such (Macaulay again) “strange theories” as the idea “that the laws, by which, in England and in other countries, the [royal] prerogative was limited, were to be regarded merely as concessions which the sovereign had freely made and might at his pleasure resume; and that any treaty which a king might conclude with his people was merely a declaration of his present intentions, and not a contract of which the performance could be demanded,” etc.

Such strange theories displeased an armed people. James I eked out his time as king of England and Scotland, but his son had less luck. As Monty Python says, “The most interesting thing about King Charles I is that he was five foot six inches tall at the start of his reign, but only four foot eight inches tall at the end of it.” Charles’s sons made it to safety in France—King Louis was their uncle. After England failed in its experiment with having no king, Charles’s sons were invited back. Charles Jr., son of the executed monarch, who had for years claimed to be a king in exile, was now Charles II for real.

Charles II was perhaps a mellow guy, as far as Stuarts went. Once (for example) when he met William Penn, and Penn (as a Quaker) refused to doff his hat for the king, Charles doffed his own. Penn asked the king why he did so, and Charles explained that it was the custom, when a man met the king, for only one of them to keep his hat on. If the “William Tell Overture” has taught me anything, it is that such behavior in a nobleman, let alone a king, is what passes for great tolerance.

But Charles had no legitimate heirs, and on his death the crown passed to his brother, the very much less mellow James II—a Stuart through and through, autocratic and aloof. He was so unpopular that Charles II’s illegitimate son Monmouth thought he could march on London and the people would rally around him, deposing the king. Monmouth was wrong, and James II killed him. But soon James II was even more unpopular, and Prince William of Orange marched on London and the people rallied around him, deposing the king. James escaped to France one step ahead of the mob, to nurse grudges and foment rebellions, unsuccessfully, for generations to come.

It was not being autocratic and aloof that did James in. It was being Catholic.

James’s mother, who was the daughter, recall, of the king of France, was therefore Catholic, of course. But James was born and raised an Anglican…until he fled England as a teenager, while Puritans decapitated his father. If you don’t want your future king to be a Catholic, maybe don’t have him grown up in a Catholic country, huh? Somewhat grudgingly, an England that still remembered Bloody Mary and Guy Fawkes tolerated a Catholic king, because it was guaranteed to be a one-time thing: James’s only two children, Mary (princess of Orange) and Anne (princess of Denmark) were from his first (late) wife, and Protestant. But in his mid fifties, James had a son with his second wife. This wife was Italian and Catholic and the specter of James III got all of England riled up. James fled to France, and for years his followers would honor him by raising a glass “to the king!” while passing said glass over a finger bowl—i.e. “to the king [over the water],” which is to say the deposed king in France. Those cunning Jacobites!

But you see how this follows: James was only Catholic because he grew up in France; he was only in France because he fled the regicides; the regicides only rose up because Scottish kings were autocratic; Scottish kings were only in England because Elizabeth had no heir; she only had no heir because getting married = decapitation. It all goes back to Henry VIII.

Mary, James’s daughter, and her husband William, jointly took the throne in James’s absence. When Mary died, William ruled alone.

Of course, that’s only a Dutchman on the English throne, and despite what they may tell you in Pennsylvania Dutch country, a Dutchman is not the same as a German. But William and Mary died without issue and were succeeded by Mary’s sister Anne. Anne had seventeen pregnancies, but only one resulted in a child who lived past the age of two—he died at eleven. Anne (“such a colourless personality,” judges Saki) died childless in 1714, but no problem, right? Anne’s half brother James (James III to be) is on the wings, waiting.

But James was Catholic and England wasn’t falling for that again!

They’d drafted up new rules for succession in 1701, excluding Catholics from the throne, and the next Protestant in line upon the death of Anne was James I’s great grandson, a fifty-four-year-old German guy from Hanover—now George I. And that’s how a German ruled England (and also Scotland, of course; and Ireland, I guess; and whatever else they claim: France, which England still claimed as its own territory until 1800, the Isle of Man, or what have you).

You’ll see how directly it follows—but you’ll also see how impossible it would be to figure out ahead of time. If Mary or Anne had been philoprogenitive; if Charles II had married a Protestant—a Swede or something—and his children had fled to Scandinavia to escape England; if the roundheads who decapitated Charles I had been a little more fun, so no one ever thought of restoring the Stuarts…no German king! Henry VIII could hardly have expected any of that, and if he had hypothesized such a chain of events, a contemporary observer would be justified in snorting incredulously. “Where’d you dream up that one, Henry?”

Just a flight of fancy.

[“Centuries past”: Peter Primrose, A Pen’orth o’ Poetry for the Poor (Harrison & Sons, 1884) p. 83; “I will never marry”: Alison Weir, The Life of Elizabeth I (Random House, 2008) p. 13; Macaulay, The History of England from the Accession of James II vol. I (Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1849) pp. 40 & 71; Monty Python Sings, “Oliver Cromwell” (1989); Saki, The Complete Short Stories (Viking, 1942) p. 286.]