What if Hannibal had marched on Rome?

Hannibal marches on Rome → A Punic imperium around the Mediterranean → Nonstop infant sacrifice → No suspicions in Bethlehem → A pagan Europe forever

[Please consider purchasing Impossible Histories, the book that is just like this essay except better researched, or pre-ordering Apprentice Academy: Sorcerers, a book unlike this essay in every way.]

Why, let us build a city of our own,

And not stand lingering here for amorous looks.

•Marlowe, Dido, Queen of Carthage (c. 1586?).

The Roman historian Livy (59 BC–17 AD) wanted nothing so much as to explain to his readers what made Romans so impressively powerful, virtuous, etc. and look! now they have an empire! His book is filled with anecdotes that are clearly intended to be illustrative of Roman greatness, but one of the most telling comes at the matter in a backhanded way.

It is this: During one of the (innumerable) Samnite wars, the Samnites manage to trap the Roman army in a ravine. The Romans are completely at the mercy of the Samnites. It’s a wonderful outcome beyond any Samnite’s wildest dreams—and so the Samnites of course undergo a crisis. They have no idea what to do! In search of advice, the triumphant commanders send a messenger speeding back to Samnium to ask the aged sage Herennius Pontius what they should do with the captive army.

The messenger returned reporting that Herennius Pontius had suggested the Samnites let the Romans go free, with all their weapons and honor intact.

Assuming that H.P. was off his nut, the Samnites sent the messenger back to get a second option from the old man. Herennius Pontius’ advice then was to murder every man jack of them.

The Samnites didn’t want to do that either, so instead they made the Romans leave their weapons and most of their clothes, and, in a hilarious bit of impish high spirits, they put yokes on the Roman leaders, and drove them like cattle back to Rome, laughing and mocking the whole time. Such jesting! What a coup!

This prank made the Romans really mad, so they came back and where are the Samnites now? The Romans (eventually) conquered them and, when they did, they didn’t make a big game of it; instead they incorporated the Samnites into their empire (which was, of course, at the time a republic).

Herennius Pontius, whose plan A and plan B were so dissonant that the Samnites feared he’d gone senile, eventually explained his reasoning to them. If they’d followed plan A and let the Romans go, the Romans would, in gratitude, call off the war. If they followed plan B and killed all the Romans, then the Romans would be in no position to continue the war. Either way, the Samnites would get what they presumably wanted, viz., an end to war on their terms. In other words, victory.

But the Samnites demonstrated that victory was not, in fact, what they wanted. What the Samnites wanted was some good larfs at the Romans’ expense. The Romans, on the other hand, wanted victory, and these two contrasting styles of warfare are why no one says “When in Samnium do as the Samnites do” or “All roads lead to Samnium” or “Samnium wasn’t built in a day.” No one cares how long it took to build Samnium.

ii.

Livy is of course less interested in dunking on Samnites than he is on praising Romans. Here’s another story he tells: Some time before the whole Samnite debacle, the Etruscan King Porsena was besieging Rome. In somewhat desperate straits, Rome sent out a volunteer, one Gaius Mucius, to slip into the besiegers’ camp and assassinate Porsena. Tragically, C. Mucius did not know what the king looked like, and accidentally assassinated the secretary standing next to him, which was embarrassing all around. Etruscans seized C. Mucius, and King Porsena threatened to burn him alive unless he spilled all about the Romans’ plans to kill him. C. Mucius merely said that he was only the first of a long line of assassins who would come out and endlessly attempt Porsena’s life, one after the other, until someone succeeded; and then, to show his contempt for the concept of being burned alive, the would-be assassin stuck his right hand into a nearby fire until it charred away to nothing. “See how cheap men hold their bodies when they care only for honor!” said C. Mucius calmly.

C. Mucius was permitted to return to Rome, where he acquired the nickname Scaevola (“Lefty”) and a land grant from the grateful Senate. Porsena, meanwhile decided that these Romans were crazy, and he packed up and left. Who wants to fight a bunch of madmen?

And that was the Romans’ schtick. They were bonkers! When a giant crack appeared in the Forum, one Marcus Curtius just jumped right in (which made it close up). T. Manlius Torquatus ordered the execution of his own son for disobeying a relatively minor order. (L. Junius Brutus ordered the executions of his two sons, but the charge was more serious.) P. Horatius, not really in a position to order anything, straight up stabbed his own sister to death for fraternizing with the enemy. These guys just did not mess around. They were like the opposite of Samnites!

It’s worth taking a moment to note how strange the story of Scaevola the Lefty is, at least to our modern understanding. The idea that a people would fanatically offer themselves to a welcome death—this is a trait we tend to assign to foreign enemies. Scaevola sounds like a Middle Eastern suicide bomber or a Japanese kamikaze pilot. He sounds other. Note how his action echoes two foreign, othering stories about the Vietnamese (from the Vietnam War era): His willingness to brave the fire reminds us of the self-immolating Buddhist monks, calmly praying as they burn to death. His willingness to lose a hand is similar to the (more fictional) scene in Apocalypse Now, the one where Col. Kurtz describes a village in which the inoculated arms of children were chopped off by their own parents. “The will to do that!” Kurtz enthuses. “Perfect, genuine, complete, crystalline, pure. And then I realized: They were stronger than we…”

How foreign (we are invited to exclaim) this practice is! Something they would do! And yet, the Romans are, for the West, the antithesis of They. The Romans are We. The whole Western tradition, the Greek and the Judeo-Christian, filters through Rome. “I consider nothing human foreign to me,” the Roman playwright Terence wrote, optimistically; well, nothing Roman is foreign to the West.

And yet there is Scaevola. I have no way out of this labyrinth, I have no solution to the riddle of how the keystone of the Western tradition could owe its glory to behaving like our stereotypes of non-Westerners. Perhaps it is merely that Rome is forever accusing itself of falling away from its ancient Republican virtues. One might say that Rome, like Punch, never was what it was. We have fallen away from the model of Scaevola. “Going downhill is the natural way.”

But really, I only bring the riddle and the labyrinth up to drive home our central point. That the Romans were apenuts insane 100% committed to victory, and they would never ever surrender to anyone.

Except there was this one guy…

iii.

As Rome was swelling from a little city state to an Italian power it came into conflict with another burgeoning city state named Carthage, situated in North Africa but with interests across the Mediterranean. Overlapping spheres of influence led to the First Punic War, which either through luck or pluck Rome managed to win. The Carthaginians were not happy about this state of affairs, though, and unfortunately for Rome Carthage was about to produce one of the all-time military geniuses. That was Hannibal. There was going to be another fight.

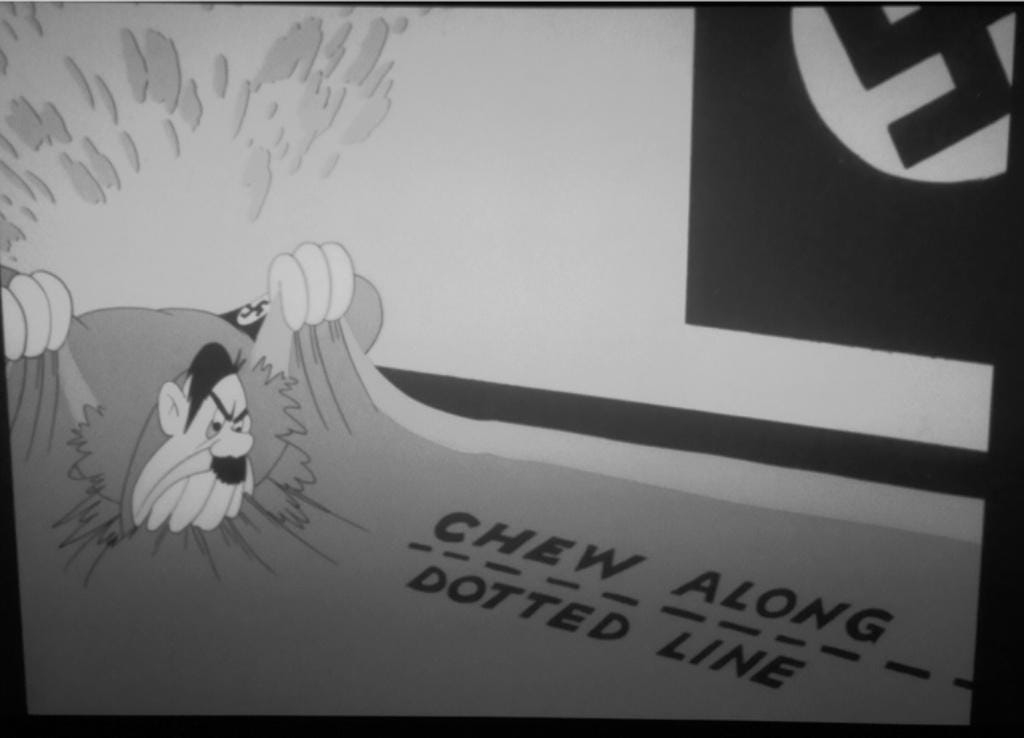

Unfortunately for Rome and ultimately unfortunately for Carthage, Hannibal’s father made the lad swear an oath at the sacrificial altar, “with his hand upon the sacred victim,” an oath of eternal hostility to Rome. This sounds more like something a pulp villain would do than a real human, or more like something a Roman historian like Livy would make up about an enemy of Rome (as he in fact does in his own book). Hitler did not really chew on carpets; Donald Trump did not really sleep with a copy of Mein Kampf under his pillow; and Hannibal’s childhood was probably not spent in quite such an on-point Romophobic fashion. But these are the stories we tell ourselves about villains.

Hannibal is hardly the most villainous of villains, and unlike Romans like Catiline (c. 108–62 BC) or Caligula (AD 12–41) the Carthaginian has inspired more admiration than hatred. Polybius states that when Hannibal made his harrowing trek over the Alps, one of his followers suggested that his starving soldiery could feast on the flesh of dead men…and Hannibal said no! Napoleon called Hannibal “the most daring, the most wonderful (étonnant) of all; so bold, so sure, so grand in all things etc.” And the intervening millennia were not exactly devoid of celebration, either.

I guess it’s fine not to eat people, but most of those celebrations leaned more Napoleanic, lauding Hannibal for his skill in generalship. Hannibal was not one of those generals (Alexander, Tamurlain) who was never defeated, but he had a streak going for a long long time. After some victories in Spain that may well have started the Second Punic War, Hannibal led (his most picturesque exploit) those elephants and armies over the Alps in an attempt to finish it on Roman soil. He kept his streak going with victories in minor skirmishes, and then in the two brilliant battles at Trebia and Trasimene.

In both battles Hannibal was in enemy territory, far from anything like a supply line, and outnumbered. In both battles he won not only decisively but humiliatingly decisively. At Trebia Hannibal hid a force in a drainage ditch behind the Roman line, and wasn’t that a surprise partway through the battle? The Romans lost some 30,000 men (out of 40,000). At Trasimene, the Roman general C. Flaminius thought he was sneaking up on Hannibal’s unsuspecting forces, unaware that the camp he was approaching was a dummy, and the real Punic army was lying in ambush. Flaminius walked into a trap, and the general sent to reinforce him (unaware that his countryman had been ambushed) walked into another, and that was another 30,000 Romans down.

The Romans could not afford to lose so many men so fast. Under the advice of a new consul, Q. Fabius Maximus, they decided to adopt a new strategy, which was not to fight Hannibal at all. I mean , the strategy was to not fight Hannibal at all. Instead, Roman forces shadowed the Punic army, picking off stragglers and foraging parties. In this way they hoped to wear the Carthaginians down—a so-called “Fabian strategy.” The later Fabian Society of H.G. Wells and G.B. Shaw got their name because they hoped to bring socialism to England gradually and without Marxist revolution; they’d just wear the British down, like Fabius, only with pamphlets and moralistic novels.

The Fabian strategy worked in the sense that Hannibal was not able to kill tens of thousands of Romans any more, but he was, instead, happy to plunder their Italian allies. Rome was not going to protect you, was Hannibal’s point, so why be loyal to it? Eventually, if this went on, the rest of Italy would turn against Rome. Eventually, there was going to have to be a fight.

That fight turned out to he the biggest disaster in Roman history (until the end, I guess), and one of the biggest disasters in all the history of military conflict: the famous battle of Cannae, 216 B.C., in which an outnumbered Hannibal outgeneraled and outfought the largest army Rome had ever assembled. Once again, Hannibal cemented his victory with a clever ruse: He placed his Gaulish allies in the center and a little ahead of the rest of his line. The entire weight of the Roman army fell upon this small part of Hannibal’s force, and Hannibal counted on the Gauls eventually breaking. When they did, when they turned tail and ran and the victorious Romans ran after them, the Roman army found that it was running into a gauntlet. Fresh Punic troops were on either side of them. Hannibal’s cavalry—always his best and most reliable weapon—rode around and sealed the trap from the back. The fleeing Gauls, realizing they were, in fact, on the winning side, turned around to face their foe again. The Romans were surrounded and although Livy (predictably) presents then displaying glorious last-stand Alamo-style valor, there was nowhere for them to go. “Hell or Hoboken by Christmas” American troops cried as they disembarked (from Hoboken) for WWI Europe, but for the Romans there would be no Hoboken, only Hades. Scratch off another, say, 50,000 Romans, most of them not captured but killed outright (other ancient sources say 80,000). “It remains [writes historian Adrian Goldsworthy] one of the bloodiest single day’s fighting is history, rivalling the massed slaughter of the British Army on the first day of the Somme offensive in 1916.”

And Cannae—that one led to panic. Rome had never faced a defeat the size of Cannae, and to have it come as the capstone of a string of defeats…

Years later, British nannies would sing to their charges:

Baby, baby, naughty baby,

Hush, you squalling thing, I say.

Peace this moment, peace, or maybe

Bonaparte will pass this way.Baby, baby, he’s a giant,

Tall and black as Rouen steeple,

And he breakfasts, dines, rely on’t,

Every day on naughty people.

So great was the threat of a French invasion in the early nineteenth century that the little corporal had become a kind of permanent boogeyman. Hannibal, who (we know) refused to eat even naughty people on principle, nevertheless took on a boogeyman role himself, and first Romans and then their cultural descendants would through the centuries silence their children with the threat: Hannibal ad portas—Hannibal is at the gates.

And yet Hannibal was not at the gates. Hannibal was nowhere near the gates. While Rome quaked in fear, Hannibal did nothing.

iv.

The Roman historian Sallust said that he chose to write about the Jugurthine War because (in part) “it was a hard-fought and bloody contest in which victories alternated with defeats”—but as the outcome of the Jugurthine War was never really in doubt, and Jugurthus was unlikely to stay in power in his kingdom in Africa, let alone travel to Italy and assault Rome there, surely this description applies better to the Second Punic War. The vicissitudes of the Carthaginians and Romans in Spain, where control of the peninsula passed back and forth several times, are on their own too complicated for me to remember.

But if the fortunes of Rome and Carthage would ebb and flow through the war (as fortunes will), in post-Cannae 216 the Romans were at their absolute low-point. The Romans were not the type to surrender, but if they ever were going to surrender, it would have been in the throes of despair that Cannae had them in. Thomas (the one from Lytton Strachey) Arnold, musing on Hannibal’s lack of action after Cannae, wrote that “there are moments when rashness is wisdom; and it may be that this was one of them. The statue of the goddess Victory in the Capitol may well have trembled in every limb on that day, and have dropped her wings, as if for ever.” But Hannibal was not rash. He did not bolt with his armies for Rome, ready for the demoralized populace to thrown themselves at his mercy. He sent a few envoys asking for surrender, but by the time they got there, Rome’s spirits if not its fortunes had bounced back. Contemptuously the Romans refused all peace overtures. The Senate made discussing capitulation a capital offense. By the time Hannibal did march to the walls of Rome four years later, the Romans jeered at him. They publicly auctioned off the land he was camped on, more or less as a joke. A decade later, as Roman armies invaded the Carthaginian strongholds in Africa, Hannibal, called home to face them, suffered his first real defeat. At the Battle of Zama, Roman general Scipio Africanus used a cunning stratagem worthy of Hannibal: He repositioned his forces so that there were long open corridors through the Roman lines. Hannibal’s war elephants—so terrifying!—charged towards the Roman soldiers who were armed with long spears and…veered off and raced down the corridors, as in only sensible. Thus were the elephants neutralized, and soon the battle went to the Romans.

Carthage capitulated and the Second Punic War was over. There would be a (brief, minor) Third Punic War, and after that there was no more Carthage.

Hannibal marches on Rome → A Punic imperium around the Mediterranean → Nonstop infant sacrifice → No suspicions in Bethlehem → A pagan Europe forever

Delenda est Chicago.

•D.H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (1923).

But what if Hannibal had been (as Thomas Arnold would say) both rash and wise? What if he’d made a dash for Rome?

Maybe nothing, of course. But maybe Rome would have surrendered. Rome’s burgeoning empire nipped in the bud, Carthage becomes the preeminent power in the western Mediterranean. It’s Carthage that gobbles up, one by one, the senescent Hellenistic states. It’s Carthage that builds a universal empire. Eventually it may fall as Rome fell, perhaps to Vandals (scourge of North Africa) and all those other barbarians. In its wake troll the Dark Ages, and then the remaining backwash of history. The question is how these would be different if a post-Roman world were a post-Punic world.

In other words, how is Carthage different from Rome?

Now, I’m not here to tell you that Rome had no culture. But, you know. There’s a lot of Greece in Rome. Rome’s greatest epic is both a sequel to and a direct homage to Greece’s two greatest epics (the first half of the Aeneid is the Odyssey, the second half the Iliad). Its finest playwrights straight-up copied Greek originals (the Terence quote above is from a play swiped from the Greek of Menander). The Roman historian Arrian titled his magnum opus Anabasis because his hero, the Greek historian Xenophon, had titled his magnum opus Anabasis—wrote a handbook on hunting in imitation of Xenophon’s handbook on hunting

(it took into account the technological innovations in venery of the intervening centuries, such as the introduction to Mediterranean society of Celtic greyhounds, faster dogs than were available to the Greeks)

—went around calling himself “the younger Xenophon”—etc. It goes without saying that Arrian wrote in Greek, as did other fashionable Roman writers, such as Claudius Aelianus, the emperor Marcus Aurelius, and a certain Roman citizen named Paul (Acts 22:27). As we’ll see below, when the emperor Augustus wanted to make an antisemitic joke, he did it partially in Greek. Jupiter and Juno may not have started out identical to Zeus and Hera, but they sure ended up that way, and, a few name changes aside, the careful reader would be challenged distinguishing the stories in an ancient Greek mythological handbook by Apollodorus from those in an ancient Roman mythological handbook by Hyginus.

There’s a lot of Greece in Rome, but that’s hardly surprising: Thanks to Alexander the Great’s conquests, there was a lot of Greece everywhere! Egypt’s most famous queen was Macedonian. Greek statuary in Greek-style cities with Greek columns can be found in archaeological digs in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and of course all points west. As Impossible History notes, the court language in medieval Ethiopia (far outside the borders of the Hellenistic conquests) was Greek.

Rome was also outside the border of Hellenistic conquest; as was Carthage. But we’ve seen how (in the words of Horace) “captive Greece captured, in turn, her uncivilised / Conquerors”—in fact, it had captured, or at least captivated Rome long before Rome conquered it—and Carthage was no more proof against the Hellenistic influence. Hannibal himself wrote books in Greek. The Carthaginian philosopher Hasdrubal traveled to Athens, assumed the Greek name Cleitomachus, and lectured in Greek. Not all but certainly some Punic statuary looks (to my admittedly untrained eye) Greek, or at least as Greek-influenced as a Gandharian Buddha.

Polybius quotes a lengthy list of Punic gods, and they are all: Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Heracles, Ares, Poseidon, etc. Polybius is quoting in Greek, and there’s no way at this late date of determining whether he’s improvising or whether the Carthaginians had assigned correspondences between their gods and the Greek gods, as the Romans did (and as the Ptolemaic Egyptians did, perhaps unwillingly). But this is the longest list of Punic gods we have. We actually don’t know a lot about Carthage. It had books (Augustine mentions them) but they have not survived (not even Hannibal’s). History, as everyone knows, is written by the victors, and that wasn’t the Carthaginians. After the Third Punic War the city was disassembled, the land it sat upon turned by a plow (but not sown with salt; that’s a later myth) as if to eliminate any memory of its existence. (Later the Romans rebuild it.)

Now, what we know of Carthage…sounds a lot like Rome. Not only was it a Hellenistic-influenced culture just outside the fringes of actual Greek hegemony, not only was it a city state on the road to empire, it was even an ex-monarchy that had become a republic. A history in which Carthage conquers the Mediterranean and becomes a blueprint for Western culture might be an awful lot like our own history.

Probably there are a million factors distinguishing Rome from Carthage, but we just don’t know what they are, so we could…we could just make them up, which feels like cheating, or we could look at the most famous difference between Carthage and Rome, which is that in Rome, people were not constantly sacrificing children to Moloch.

ii.

Human sacrifice, like cannibalism (or sleeping with Mein Kampf under one’s pillow), is something that people always want to ascribe to the other fellow. And yet, the evidence indicates that human sacrifice was actually incredibly common. Even among people we would prefer it not to be common among.

When (on the even of the Trojan War) Kalchas tells Agamemnon that if he wants to sail for Troy he’ll have to sacrifice his daughter to Artemis, Agamemnon, you’ll notice, does not say, “Sacrifice a person? I’ve never heard of such a thing!” He may say, “Sound the trumpet…Our war is done” (i.e. no, I won’t); he may say, “I have no choice now” (i.e. okay, I will); but he’s never baffled.

When (sometime earlier) God tells Abraham, to take his son to Moriah and “offer him there for a burnt offering,” Abraham doesn’t spend any time scratching his head. He’s too busy getting up “early in the morning” to do the deed (Gen 22:2–3). Abraham had put up more of a fight to save Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen 18:23ff)! Years later, Jephthah more or less accidentally offers his daughter “for a burnt offering.” No ram in a thicket this time: Jephthah “did with her according to his vow which he had vowed” (Judges 11: 31,39). Further years later, apparently under the bale influence of Canaanites (i.e. Phoenicians), things got much worse (Jeremiah 7:21).

When (in Dark Age Britain) Vortigern’s wizards tell him to sacrifice a child and sprinkle his blood on the mortar and stones of his new tower—well, it doesn’t end up happening, because the kid turned out to be Merlin, but you can see how this stuff is all over the place. Everyone knows the Aztecs just sacrificed people willy-nilly, but human sacrifice went on in pre-Columbian North America, too. James George Frazer preserves an account from around 1837 (!) of a teenage girl shot with arrows by the Pawnee, her flesh cut to pieces and her blood sprinkled on the corn. Apollonius of Tyana—one of the greatest of ancient philosophers—quelled a plague in Ephesus by getting the populace to stone a beggar, Shirley Jackson–style. The Ephesians, at least, were hesitant to kill an innocent man…but they did it. It was the first century AD, sometime around the year 65. Apollonius was the wisest man then living!

The Vikings did it. The druids did it. The Polynesians did it. “Among the Kangra mountains of the Punjaub a girl used to be annually sacrificed to an old cedar-tree, the families of the village taking it in turn to supply the victim. The tree was cut down not very many years ago.”

The Romans practiced occasional human sacrifice themselves, including once right after Cannae, when they buried a man and a woman alive in a cattle market down by the docks—apparently as instructed by the Sibylline books. Lord Macaulay was scandalized by the idea, and called one classicist a “dunce, or something worse” for suggesting that the Romans indulged—but Lord Macaulay was in denial.

Add on all the ambiguous situations—aren’t witch hunts just human sacrifice with a legalistic patina? After a society gets embarrassed sacrificing its citizenry, it dresses them up (“this isn’t my nose, it’s a false one”) as witches and then sacrifices them. We should consider Salem a site of sacrifice.

So with everyone sacrificing people left and right—if you’re going to get a name for human sacrifice, you really have to ramp it up. You have to go for it. The Aztecs got famous for it. Summerisle, maybe. And then there was Moloch.

Not Moloch, actually—the Carthaginians offered child sacrifices to “Cronus,” a Latin name for a Punic deity: possibly Baal Hammon. Moloch is a Hebrew name for a Phoenician god: possibly, since Moloch looks like a corruption of the word for king, Baal, whose name just means lord. Perhaps I should say it’s become traditional to interpret Moloch as a Phoenician god, as the references in the bible are vague and confusing. More precisely, it’s become traditional to interpret Moloch as a Phoenician god to whom Phoenicians offered child sacrifices, which is important because Carthage was a Phoenician colony.

As Jeremiah points out (above), child-sacrifice is a surprisingly exportable custom. From Phoenicia the Carthaginians may have brought their ancient practice west. Greek and Roman authors were pretty sure that child sacrifice (usually by immolation) went on in Carthage. Plutarch says the Carthaginians were so eager to sacrifice children that the childless would purchase poor children for the purpose—the child’s mother would have to watch it die, and if she shed a tear she forfeited the payment. Diodorus Siculus elaborates that in the fourth century BC Cronus was angered by these subpar ersatz sacrifices, and “turned against” the city, leaving Carthage liable to military defeat. The Carthaginians quickly sacrificed two hundred of their noblest children to Cronus to stave off disaster.

Tertullian (who lived in Roman-rebuilt Carthage) claimed that child sacrifice was still being carried out there in AD 200 (!), albeit in secret, as the Romans had banned the practice.

If there’s one thing contemporary political discourse should have taught us, it’s that claiming the other side is harming children is a fine way to slander your opponents; Rome had an incentive to present the civilization it destroyed as more or less monstrous, while Christian writers always had an incentive to present pagans in general as sacrifice-happy fiends. It’s probably good to take all this with a grain of salt. Older authors accepted the Punic ritual of child sacrifice uncritically; by the twentieth century the pendulum had swung the other way, and scholars began stressing the propagandistic nature of saying my enemies kill ever so many children; more recently the pendulum’s back to infanticide. In 2014 classicist Josephine Quinn claimed “the archaeological, literary, and documentary evidence for child sacrifice [in Carthage] is overwhelming”—referring to a paper that presumably backs that assertion up, but that I don’t have access to.

I’m not the boss of pendulums but I understand that this one may go back to viewing sacrifice as propaganda. But here we are right now; so let’s give it to them. Let’s add this to our assumptions. Just as we have assumed that if Hannibal marches on Rome, Rome will capitulate; just as we have assumed that a victorious Carthage means a Punic Mediterranean and a Punic imperium; let us assume that while everyone sacrifices some humans, the Carthaginians sacrifice humans (especially children) on a larger scale than most. Here’s our difference between Carthage and Rome. Killing kids.

iii.

Sooooo…what historical peg involving killing children can we hang an alternate history on?

Sometime around 4 BC Herod, king of Judea, frightened by astrology, ordered slain all children “two years old and under” in the environs of Bethlehem (Matthew 2:16). It didn’t go well. In the confusion (according to the pagan writer Macrobius) Herod’s own son was accidentally killed; when the emperor Augustus heard about it, he quipped that “It’s better to be Herod’s pig [huos] than his son [huios],” as the Jewish Herod had no reason to slaughter pigs. Even worse, Herod didn’t even get the kid he was looking for; his parents, perhaps concerned by all the children being rounded up and killed, slipped off to Egypt. Soon Herod was dead, the kid came back from Egypt, and, as you’re doubtless aware, three decades later that kid was preaching the gospel and starting the stone “rolling through Babylon”—that’s Jesus, of course.

Imagine, for a moment, that Herod was not a client king of Rome, but rather a client king of Carthage. Rounding up children for massacre—we just call that a Tuesday. Joseph and Mary would notice nothing unusual about it. Would they flee to Egypt? Egypt was Punic territory, too, and for all they knew someone would just round their son up there anyway. Stay in Bethlehem, and Christianity gets quite literally snuffed in the cradle.

Rather than creating a world very much like our own, Carthaginian hegemony would create a world in which Baal-paganism flourished unchecked through the millennia. Happy Baaloween, everyone!

iv.

Unless an angel appears to Joseph and straight-up tells him to go to Egypt (Matthew 2:13). Can’t change history if an angel comes and messes with you.

Sources: “See how cheap men hold”: Livy, The Early History of Rome (Penguin, 1987) p. 119; Terence, The Complete Comedies of Terence (Rutgers UP, 1974) p. 74; “with his hand upon the sacred victim”: Livy, The War with Hannibal (Penguin, 1972) p. 23; Polybius states: Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin, 1979) p. 401; Napoleon: G.B. Malleson, Ambushes and Surprises: Being a Description of Some of the Most Famous Instances of the Leading into Ambush and the Surprise of Armies, from the Time of Hannibal to the Period of the Indian Mutiny (W.H. Allen, 1885) p. 1; Goldsworthy, Cannae (Phoenix, 2001) p. 159; “Baby, baby”: Wm. S. & Cecil Baring-Gould, The Annotated Mother Goose (Meridian/New American Library, 1967) p. 226; Sallust, The Jugurthine War / The Conspiracy of Catiline (Penguin, 1963) p. 38; Arnold, History of Rome vol. III (Gilbert & Rivington, 1850) p. 144; faster dogs than were available to the Greeks: v. William Dansey, ed., Arrian on Coursing: The Cynegeticus of the Younger Xenophon (J. Bohn, 1831) p. 71; Impossible Histories, op. cit. p. 323; Horace, The Epistles; Polybius quotes: Dexter Hoyos, The Carthaginians (Routledge, 2010) p. 94; Augustine, Letter 17; Agamemnon: Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis (Image, 2022) pp. 19 & 47; Vortigern: Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain (Penguin, 1966) p. 167; Frazer, The Golden Bough (Macmillan, 1969) p. 501; Apollonius: Kenneth S. Guthrie, op. cit. p. 25—and cf. the discussion in René Girard, I Saw Satan Fall like Lightning (Orbis, 2001) pp. 49ff.; “Among the Kangra”: Frazer p. 130; Macaulay: Thatcher Thayer, attr., Some Inquiries Concerning Human Sacrifices among the Romans (Sidney S. Rider, 1878) p. 8; Plutarch, Moralia; Diodorus Siculus, Library of History; Tertullian: Hoyos p. 101; Quinn: “Ancient Carthaginians Really Did Sacrifice Their Children”; Macrobius, Saturnalia vol. I (Loeb) (Harvard UP, 2011) p. 349—and v. A. Smythe Palmer, Some Curios from a Word-Collector’s Cabinet (Routledge, n.d.) p. 84.