These are annotations for the first chapter of the book Impossible Histories. I’m not saying you need to keep a copy of IH open next to you as you read, but it might make some things clearer?

p. 9

•epigraph: I wanted each chapter to start with an epigraph, but they got cut. For the record, the epigraph here was to be:

The anarchist was courageous; he risked his life to take a life. The nihilist was a man, despite his crimes of violence.

•Ole Hanson, Americanism versus Bolshevism (1920).

•“pluck” or “grit”: Horatio Alger, dean of American boy’s adventure literature—meaning neither the first nor best practitioner, but rather the most prolific—wrote a book entitled Grit (1892), and at least two with titular pluck: Luck and Pluck (1869) and Andy Grant’s Pluck (1895). His young heroes didn’t tend to go to war, of course.

•Dick & Co.: Never an ill wind etc., and WWI had to be lucky for someone. Well, that someone was H. Irving Hancock, who had at some time early in the twentieth century started writing a series of kid’s books about six young friends from the town of Gridley known as Dick & Co.

(Dick & Co. is quite clearly named after the 1890s Kipling stories known as Stalky & Co., collected in book form in 1899, which deal with a group of school chums, although, beyond the chums aspect, no two texts could be further apart than Stalky & Co. and Dick & Co.)

The six chums started in grammar school, and, book by book, aged through high school, one book per school year (with additional books detailing their summer vacations). The books lean heavily on their sports exploits (as was the custom of the time, due to the popularity of the Frank Merriwell series of dime novels), but occasionally the boys foil a crime or get accused of cheating and have to clear their names, etc. It’s all good fun in a harmless way.

But when the boys graduated high school in 1910, the six friends split up. Two go to West Point to train as army officers. Two go to Annapolis to train as naval officers. Two become engineers and head out west to survey things for the US government. That’s three new series—West Point, Annapolis, and Young Engineers—each with two characters from Gridley.

You may think that Hancock would be running out of things for the lads to do as they graduate college and become military officers in peacetime—but lucky for Hancock, not long after they graduate, the world is at war! Dick & Co. fight the Kaiser!

(Hancock cranks books out at a rate of more than one a year, so there’s a slight lag between graduation and the start of hostilities.)

It turns out that Hancock had previously started Uncle Sam’s Boys, a series of books in 1910 about lads entering the peacetime army (the first one is Uncle Sam’s Boys in the Ranks, referenced on page 16 of IH); when the war starts, the officers of Dick & Co. team up with the non-commissioned heroes of the Uncle Sam’s Boys books.

I haven’t read these later books, so I’m not sure how the two series dovetail, nor how the Young Engineers fit in. Hancock’s series outlast the war—one year after Armistice, he put out Uncle Sam’s Boys with Pershing’s Troops; or, Dick Prescott at Grips with the Boche, a book I also haven’t read but whose very title indicates it is a team-up.

p. 10

•Clair W. Hayes: These books are eminently quotable, but there’s only so much I could fit in IH. Here’s the kind of action scene typical of WWI boy’s adventure literature:

Now Hal and Chester found themselves in the midst of the battle, in the fiercest of the fighting. Sent forward with orders, they found themselves in the center of the sudden charge. Neither was minded to turn back, but they managed to single each other out and soon were fighting side by side. Blood streamed from a wound in Hal’s cheek, where a German bayonet had pricked him slightly. Chester was unwounded.

Suddenly Hal found himself engaged with a German officer. With a swift move he swept aside his opponent’s blade and felled him to the earth. At the same moment a tall German soldier, thinking to deprive the lad of his weapon, brought his rifle down upon Hal’s sword.

But the boy’s grip was firm and the sword snapped off near the hilt. Quickly Hal sprang forward, and before the German soldier could recover himself, the lad cut him down with his broken sword. Then, stooping, he picked up the sword which had fallen from the hands of the German officer, and sprang to the aid of Chester, who was fiercely engaged with two of the enemy, one an officer, the other a trooper.

One swift stroke of the boy’s sword and the soldier was laid low. At the same instant Chester’s sword slipped through his opponent’s guard and the latter went to the ground, a deep wound in his side.

“Good work!” Chester found time to pant to Hal, and a second later both lads were once more too busy for speech. Etc.

(Hayes, The Boy Allies on the Firing Line; or, Twelve Days Battle Along the Marne (A.L. Burt, 1915) pp. 30–31.)

•Over the course of thirteen books: This is my count of the number of Hal & Chester Boy Allies books. There were ten additional Boy Allies books about two other strapping lads and their adventures with the navy, so the series has total of twenty-three volumes; the series outlasted the war.

The next series by Clare W. Hayes (another pen name) was 1922’s “Boy Rangers” books about two strapping lads’ deputative adventures with the Pennsylvania state troopers. It has the distinction of being the most violent series of children books ever released by a mainstream press (A.L. Burt).)

•It was so much fun!: Humor from the Great War abounds, and although some of it has a requisite tinge of melancholy, such as A.P. Herbert’s Half-Hours at Helles, others, such as Edward Streeter’s Dere Mable series or Percy Crosby’s That Rookie from the 13th Squad, do not.

This despite the fact that Crosby’s postwar work is melancholy as all get out.

p. 11

•Archduke Ferdinand: Thomas Pynchon pulled off the neat trick of combining anarchists and Archduke Ferdinand and coming up only with pleasant hijinks in his mammoth 2006 novel Against the Day. I should go digging through it to find a cleverly relevant quote, but I’m too intimidated to even take its mammoth bulk off the shelf…

•six heads of state: This list of the six is Barbara Tuchman’s: “President Carnot of France in 1894, Premier Canovas of Spain in 1897, Empress Elizabeth of Austria in 1898, King Humbert of Italy in 1900, President McKinley of the United States in 1901, and another Premier of Spain, Canalejas, in 1912.” (Tuchman, The Proud Tower (Macmillan, 1966) p. 63.)

p. 12

•Serbia was de facto allied with Russia: Although there was no official alliance between Serbia and Russia, the Czar did say, “For Serbia we shall do everything,” so you can see how that might work the same way. (Roger Parkinson, The Origins of World War One (Wayland, 1973) p. 67).

p. 13

•epigraph: Oh, yeah, I wanted the second half of each chapter to have an epigraph, too, because I have little or no self control. The epigraph here was to be:

To eradicate the disease called Prussianism may, unless we are compelled to make the surgery more terrible and destructive than it need be, set free a deeply buried, blind, at present almost inarticulate Germany, which, when it opens its eyes and feels its strength, will recognise that its worst enemies were not those who now face it along a thousand miles of steel and flame.

•T.W. Rolleston, introduction to Because I Am a German (1916).

p.14

•The Reverend Jim Jones: Here’s Jim Jones in 1974: “I’d do anything to get people to be socialists. Anything except violence to them! (Pause) (Voice rises) Anything!”

Peoples Temple is one of those things, like Stalinism, that may look bonkers in retrospect, but which was just a normal part of progressive discourse at the time. Eldridge Cleaver and Angela Davis radioed messages of encouragement (“we are with you, and we appreciate everything you have done” etc.) to Jonestown, for example, with Davis somewhat notoriously stoking Jones’s paranoia with an unfortunate reference to “a conspiracy. A very profound conspiracy designed to destroy the contributions which you have made to our struggle.” One year later, everyone is Jonestown was dead. Ah, but Perhaps Jones’s paranoia needed no stoking.

(Transcripts courtesy the Jonestown Institute, q.v.)

p. 15

•a legitimate ruse: The attitude the prewar past had towards dishonesty is hard to reclaim, except of course through literature. I think Frances Hodgson Burnett, or rather one of her characters, said it best (ca. 1905):

“Lies—well, you see, they are not only wicked—they’re vulgar. Sometimes…I’ve thought perhaps I might do something wicked—I might suddenly fly into a rage and kill Miss Minchin, you know, when she was ill-treating me—but I couldn’t be vulgar.” (Burnett, A Little Princess (Harper Trophy, 1987) p. 172.)

•“Seven years ago” from 1921 is 1914: Of course, the poem is titled “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” and 1919 – 7 = 1912. 1912 is when the Third Home Rule Bill started all the consternation in Northern Ireland, and, look, I’m aware that many (most?) people view Yeats’s poem as being about recent Irish history, but…come on, it’s really about WWI. The poem presents an apocalypse of Western culture, not just Ireland. Maybe if I knew more (i.e. anything) about C20 Irish history I’d change my tune.

•the retrospective novels: Honestly, I should have included here A Farewell to Arms, which is filled with this kind of despair, unthinkable (?) before WWI:

“If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them. The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.” (Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (Scribner, 1997) p. 226.)

p. 17

•fifty thousand at the Battle of Plassey: Lord Macaulay wrote, with characteristic verve: “with the loss of twenty-two soldiers killed and fifty wounded, Clive…scattered an army of near sixty thousand men, and subdued an empire larger and more populous than Great Britain.” Macmillan’s fact checker challenged me on the number sixty thousand, and I just assumed Macaulay was wrong, which is why it’s now fifty thousand. (Macaulay, Essays on Clive and Hastings (Scott, Forseman, 1909) p. 89.)

p.18

•“all was lost but our honour”: I didn’t know this at the time of writing, but Scott was actually quoting Francis I (1494–1547) of France (after the Battle of Pavia). For all I know, Francis was quoting someone else, and it’s elephants all the way down. (William Tegg, The Mixture for Low Spirits: Being a Compound of Witty Sayings of Many People in Many Climes, Both Humourous and Pathetic (Tegg & Co., 1875) p. 93.)

•Georges Clemenceau: Here’s the guy, as painted by Édouard Manet.

Obviously every famous person gets a portrait, and I’m not in the business of trotting each one out, but I put this one here because I think it’s funny how much Clemenceau hated the painting, saying (according to Wikipedia): “Very bad, I don’t have it and I don't mind that. It is at the Louvre, I ask myself why we put it there.” (There’ll be more of people hating on Manet in a future chapter’s annotations. I mean, I don’t even like his work much myself.)

•A 1916 political cartoon:

p. 19

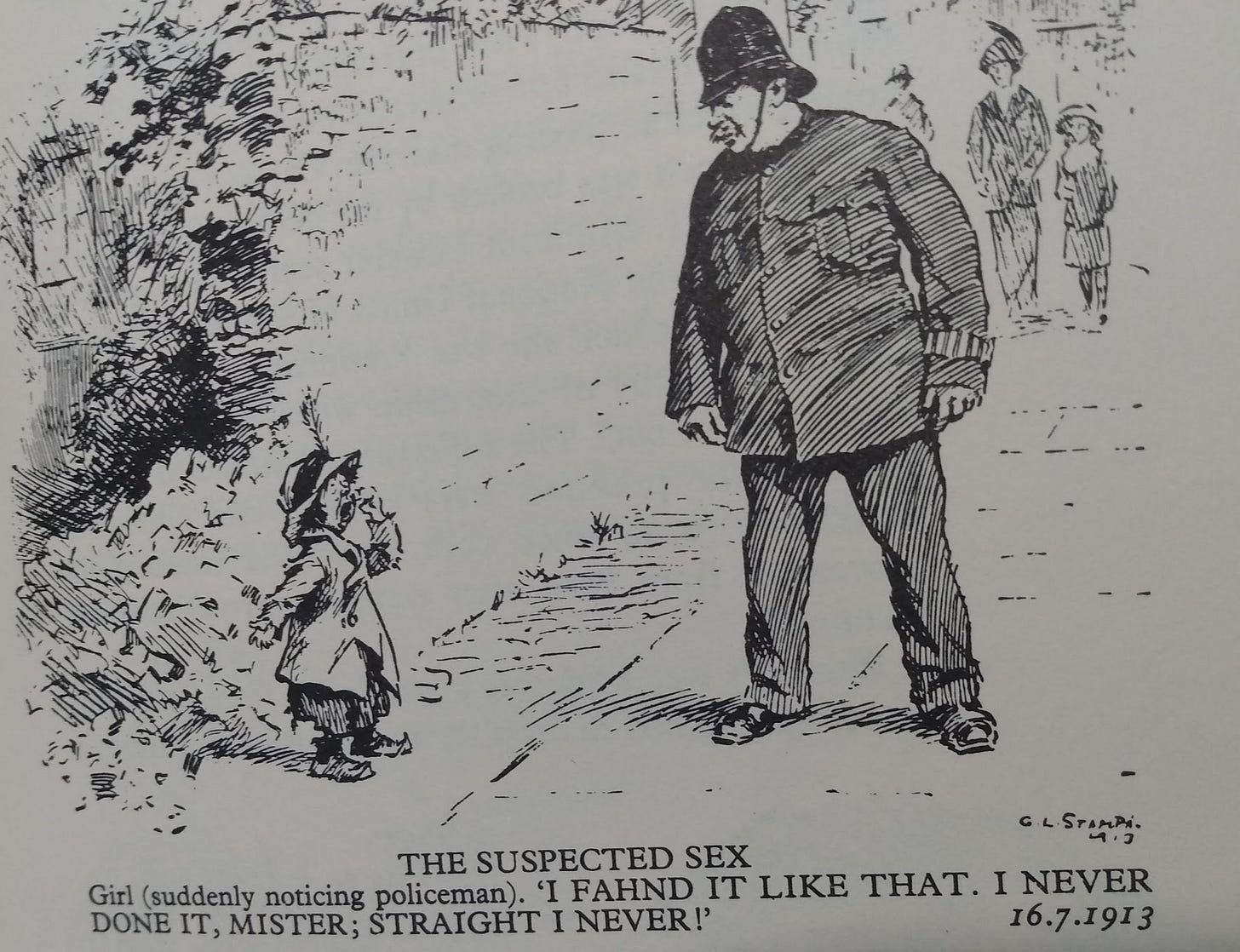

One 1913 Punch cartoon:

Here’s another Punch cartoon on the same subject (and pulled from the same source, Constance Rover, op. cit.):

•the British government assumed few women would admit to being over thirty: I got this assertion from a “real” source (Graves & Hodge, as cited in the text), but perhaps it was a standard joke at the time. A 1977 US joke book about “women’s libbers” could similarly assert: “One thing is for sure. There’ll never be a woman in the White House. How are you going to get one to admit to being 35?” I could see contemporary wits sharing the same idea in 1918, and would Robert Graves be able to resist? [Phil Hirsch & Paul Laikin, Women’s Libbers and Male Chauvinists (Pyramid, 1977) p. 123.]

p. 21

•temperance: So many other examples! But I’ll limit myself to just one.

In Horatio Alger’s Robert Coverdale’s Struggle, Robert’s aunt, speaks “cheerfully” and perhaps too on-point: “Tea’s all ready, Robert,” she says. “The smell of it does me good. It’s better than all the liquor in the world!”

•a bunch of Huns: I’m really not trying to upset anyone, so often, when I write something jerky and a more sensitive soul wants me to change it, sure, I try to play ball. But some of the good people overseeing this book really wanted me to ditch the Hun angle, because it was offensive to Germans. If the Germans of the nineteen-teens didn’t want to get called Huns they shouldn’t have invaded Belgium! If I can’t make fun of Germans, where will I be? Are the French next?

p. 22

•an epic poem in blank verse: Some parts of the poem are in other styles, but a lot of it is blank verse. It’s not very good.

•women could vote in some capacity in twenty-seven states: Was it really twenty-seven? It depends on how much you stretch “in some capacity.” According to the Women’s Suffrage Yearbook for 1917 (see p. 14), thirty states (and the territory of Alaska) permitted women to vote, at the time, in school board elections. Some places, for example Heritage here, take this bit of information and seem to interpret it as meaning that before the Nineteenth Amendment (Heritage’s words): “thirty states and one territory already permitted women to vote in at least some aspect in the selection of members of the House (and by then the Senate) or presidential electors.” I don’t think this is true, and just a confusion based on the Yearbook report, but I’m ready to be proved wrong.

p. 23

•Pearson thought this was a good thing: Pearson wasn’t alone. In 1922, H.A. D’Arcy, author of the popular temperance poem “The Face upon the [Barroom] Floor,” wrote: “I have been often told that my story set the pace for prohibition. I sincerely hope not. If I thought I had helped that unfortunate law, I would walk down to the dock and kick myself into the river.”

[Capt. Billy’s Whiz Bang vol. III no. 20 (About, 2008) p. 13.]