The case against the metric system

Why? Was it invented by French communists or something?

“Down with metrics! We don’t need no foreign rulers!”

•Cracked magazine, ca. 1982.

I’m not here to tell you not to use the metric system. It’s fine, the metric system is fine. Like most systems, it has good parts and bad parts. I am here to tell you that the metric system as it is generally sold in America, is a bill of goods. If the metric system could help you you probably already use. Everyone else is just getting lied to by people with mental problems.

Like many Americans, I got sold the metric system in public school. Here’s how it worked. A teacher or film strip would announce: “As you know, class, there are 5,280 feet in a mile. How many feet are in eight miles? I’ll wait.” We were compelled, at that point, to do furious calculations on scratch paper. “Now,” continued the film strip or teacher, “there are 1,000 meters in a kilometer. How many meters are in eight kilometers? Eight thousand! I did it in my head! The metric system is better, case closed.”

If you find this demonstration persuasive, I would like to sell you a boat after challenging your car to a race across a lake.

But the film strip is undaunted. The metric system makes sense! There are kilometers and hectometers and decameters and meters and decimeters and centimeters and millimeters, and once you have those down you’re all set, and things are easy and at last life is nice and orderly. The end.

What no film strip will ask you is: How often in your life, outside of classroom exercises, will you have to convert feet to miles? Look back over your life and try to parse it out. I think I’ve done it more often than most people (thanks, wargaming!) but I haven’t done it very often. Maybe you’re an engineer and would do it every day if you didn’t already use the metric system, but you do use the metric system, so you never convert feet to miles anyway.

Converting meters to kilometers is the hectogram of math problems. I mean, like a hectogram, it never comes up in reality. Although I have confidently converted hectograms to decagrams and decameters to hectometers in the classroom, these are not real-world problems that will ever come up, because no one has ever used a decameter, except as a typo for decimeter. The metric system makes sense at the expense of having extra deadwood units that never get used. These are the equivalent of the imperial system’s rod or furlong, except no one brings out the rod and furlong with a big grin on their face to prove that a system is logical.

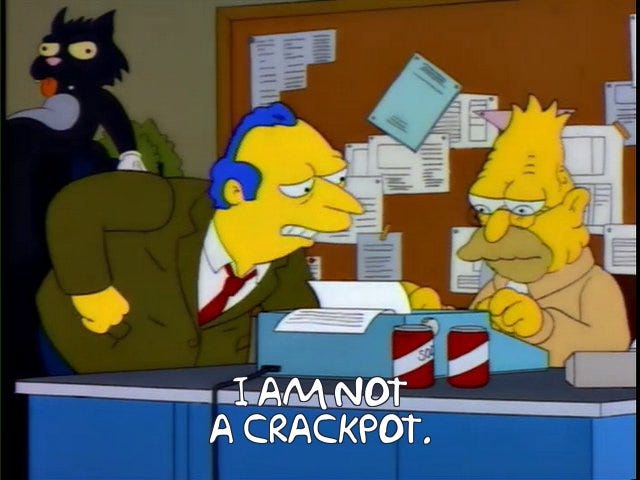

I’ve mentioned this before, but it was hidden in a mass of footnotes, and it’s my favorite example, so I’ll trot it out again. Modernism is two-thirds an attempt to assuage the OCD brain problems of H.G. Wells (and his ilk), as we can see in Wells’s utopian novel The World Set Free. How do we know the world is a utopia? We know because humans finally manage to “nail down Easter,” thereby freeing us at last of the inconvenience of looking at a calendar once a year. In fact, the whole “30 days hath September” nonsense is tidied up, and, as Wells, says, “In these matters [he means fixing Easter and February], as in so many matters, the new civilisation came as a simplification of ancient complications.”

I’m not here to rain on Wells's parade, but the truth is the complication of Easter inconveniences approximately zero people, at least since the Middle Ages—I say approximately, because four or five ecclesiastical types presumably had to pull out an astronomical ephemera every few years, and even this is now done by computer. But the complication of Easter tortured Wells like a festering sore. Every day of his life he woke up in a cold sweat. “Have we nailed down Easter yet?” he would ask his robot butler. “Am I sufficiently a parody of Mr. Spock?”

You’ll note, though, that even if we all adopted the metric system (as we do indeed in The World Set Free, just as we abolish irregular plurals from English), Wells would not be happy. That’s because the names of metric units are all cumbersome three- or four-syllable words, so even people who use metric units refuse to call them by the right name. The army calls a kilometer a click. Drug dealers call a kilogram a kilo. According to Wiktionary the Dutch call a hectogram an ons. You’ll notice that this ruins the purpose of having the names be tidy and organized! Wells will spend the rest of his life furiously demanding that the army uses all four syllables if kilometer every time it is uttered.

But if the metric system doesn’t have regularized unit names, and if its ease in conversion never comes up, at least we can be content with the knowledge that if we ever had to convert meters to kilometers—on a gameshow, perhaps—it would be quicker than the miles and feet problem. Buuuuuut…of course, it no longer takes furious scratching to figure out how many feet in eight miles, because you can just put the problem to your phone. The imperial system, like many old systems, was optimized for a time when people had to keep information in their heads, and thus a foot has twelve inches so you can divide it by two or three or four in your head without getting a cumbersome decimal. The metric system was optimized for a brief period of history when everyone had access to pens and paper but not to calculators. Now that we have devices that can serve as both calculators and notepads, nothing is optimized for anything.

George Orwell, who was usually right about everything except economics, was not exactly a fan of the metric system. His cranky take on it is worth reading in full, but let’s note just for a moment the problem with older literature, which will be filled with passages that make little sense to generations that cannot comprehend miles or gallons. Insofar as whatever shadowy Masonic forces control the zeitgeist are terrified by the idea that an adult human can be entertained for life by free public-domain content, alienating a potential readership from free entertainment is a value add for them. The zeitgeist doesn’t want you to read old books…if it did, the zeitgeist would still be capitalized (as it regularly was until very recently: Zeitgeist). But perhaps some of us find it beneficial to learn that there are three score and ten miles to Babylon. I probably sound paranoid now, though.

It turns out that there is, in fact, a perfectly good argument to be made for the metric system, but no school curriculum mentioned it, and any that tried would probably get censu/ored. We’ll never be told the real reason to use the metric system, which is merely that it’s useful for people from other countries to be able to figure out how large, heavy, or far things are in America. Since Americans learn at least metric rudiments, and can dredge this metric literacy up if they need to, the rest of the world’s use of metric is very convenient: If you (an American) travel to Japan, you may not know what you are buying in the grocery story, because it will be labeled in Japanese; but you’ll know you’re buying 22g of it. This gives American tourists abroad an advantage that most other countries’ tourists don’t have when they arrive in America.

The reason to take on the metric system is to abandon this advantage—merely in the name of fairness.

Blah blah one world government blah blah lizard people blah. I assume there are two kinds of public schools extant in American, and one kind will not want to encourage kids to surrender American sovereignty; the other kind, of course, believes measuring things is colonialist, and is hardly in a position to teach the metric system.

So (in conclusion) use the metric system if you want to. Maybe you even should! Just don’t pretend as you use it that you’re not the bad guys from The Giver blah blah lizard people blah.

It works well for us in Canada. Americans are just contrary about giving up Imperial.