Weird Books part 1

In no particular order, five weird books you may enjoy; brief reviews.

•The First Little Pet Book with Ten Short Stories in Words of Three and Four Letters by Aunt Fanny (1867).

Long before the dawn of Oulipo, well-established children’s author Aunt Fanny (not her real name) contrived a challenge for herself: to write a book entirely made up of words with four or fewer letters: In fact, about half the book is in words of three or fewer letters, with the occasional cheat (“mam-ma”). In true Oulipian style, Fanny describes writing this way as engendering is her “the pleasing emotions of a lunatic confined in a strait-jacket.”

Why try such a thing? According to Aunt Fanny, it was simply what her public craved. “Many and many a time” (she writes) “mothers have come to the author with the piteous plaint: ‘O Aunt Fanny! we are perfectly worn out with your [oeuvre]; we have read them to our little children, who have not yet conquered the compound mysteries of the alphabet, until we know them by heart; do, do write some books in words of one syllable, which they can read for themselves.’”

Aunt Fanny (“the author” in the above extract) was the pen-name of Frances Barrow; she worked at times in conjunction with her daughter, Sarah Leaming Barrow Holly, who published under the surprisingly accurate non-de-plume Aunt Fanny’s Daughter. I’ll admit I’m not really a fan of either author, their blend of sentimentality and pseudo-erotic exultation over the deaths of children no longer being in vogue; but there’s something about trying to write a story with three-letter words that brings out the weirdness in the squarest writer. For example, there is the story of Sam, a bad boy. His mam-ma bid him not to go in the hut. For the hut has an ax! But Sam ran in the hut, and, yes, cut off his toe.

“It is no fun at all to get a big toe cut off, for Sam had to lie in bed, and cry all day; and the pig ate up his big toe. He can not buy a new toe. He has but one big toe now. So you see how bad it is not to do as you are bid.”

The pig is the mot juste.

Then again, another story has this useful moral: “Let me say to you, if you get a pie, and it is too hot to eat, do not put it on the top of a big tin pot, in the air, and go off to see a cat or a dog, for if you do, may be a sly old ape may get at the pie, and eat it all up.”

The four letter stories are saner, and therefore, by our principles, less interesting.

—Where can I read this book?: Here or here.

•The Poems and Teachings of His Holy Majesty the Royal Crown Prince Obimingo Oboginimi edited by Leonardo E. Bonobo (2020).

According to Leonardo Bonobo’s introduction, Royal Crown Prince Obimingo Oboginimi is “perhaps the most mysterious member of royalty in the world.” Oboginimi “is believed to be a direct decedent of the first King of central Africa's Bantu people”; he “has never been photographed and was unknown to the outside world until 2017.”

Permit me to continue to quote, through the magic of fair use, copyrighted material: “As a nomad, he [Oboginimi] silently travels the vast aboriginal jungles of central Africa with his wives, children and a small legion of extremely loyal guards comprised from various Bantu clans. The guards have sworn a holy oath to protect him and the divine secrets.

“For years the various clans of Bantu kingdom have kept his existence secret, for he is considered the holy of holies. The multiple Kings of Bantu warned they will defend him at all cost and defend his words.

“He has only been seen and provided an audience with an outsider once; that person was a missionary.…

“The Prince is said to speak in riddles and short statements, and this book represents his spoken words.

“His poems, sonnets, hiakus [sic] and riddles were given to a missionary who in turn provided the translations to me. The exact meaning of his statements is unknown to outsiders since there are over 500 Bantu dialects. His words are very moving.”

Now, that is one of the best set-ups for a book I’ve ever read. An itinerant prophet-king, dispensing gnomic wisdom!

Unfortunately, the teachings are not very teachy. They’re mostly just center-justified journeyman nature poetry, occasionally haikuish and even pleasant.

In dark water

the fish swims in silence.

Silence.

In moonlight the hyenas cry.

In the night rain coolness comes.

Moonlight dies for the sun.

If such nature poetry is teaching, it is teaching that is too abstruse for me to recognize as such; at other times the poetry, contrarily, is too on-point:

Happiness is here.

It is not in the deepness of the dark or the light.

In the kingdom of the monkeys joy is found.

Watch them play, watch them feed, watch them tend their young.

They live in harmony and work in harmony.

They make my soul happy.

This does not strike me as a particularly well-observed description of monkeys, but I have hardly spent my entire life wandering the heart of Africa.

Although ostensibly Oboginimi has been known to the world at large since 2017, I can find no 2017 record of his “coming out.” Every search result for Obimingo Oboginimi just returns this very book. Your real question may be: Just who is Dr. Leonardo E. Bonobo that a missionary should hand over secret teachings to him? He has authored three additional books under various permutations of his name, and none of them give a compelling answer. Two of the books are collections of shocking and gruesome photographs. The third is The Big Fat Book of Hillary's Top Ten Accomplishments: The Shortest Book in the World, which is actually, according to Amazon, 62 pages long.

Amazon also provides an about-the-author, which is even more clearly fraud than The Poems and Teachings: “Dr. Leonardo Enoch Bonobo is recognized as the world's foremost primate scholar in the field of political science, philosophy, medicine and the cerebral deficiencies of politicians. He has earned four PhDs, maybe 5, and a law degree from various Ivy League Universities. As a law student he interned with the U.S. Supreme Court and later interned at the White House under President William Clinton [etc. etc.].”

In case it’s not clear from the brief excerpt I’ve provided, the (lengthy) about-the-author is not really fraud: It’s satire! No one is supposed to believe that Bonobo turned down both the Nobel Peace Prize and a reality TV vehicle. No one is supposed to believe that Democrats once “begged him to run for governor” of California on the basis of his “sex appeal.” He’s clearly joking. The Big Fat Book of Hillary's Top Ten Accomplishments may not be funny, but it is also clearly a joke.

And yet The Poems and Teachings of His Holy Majesty the Royal Crown Prince Obimingo Oboginimi, although doubtless false, is not a joke. It doesn’t even nod towards funny. A secret Bantu king may be ridiculous, but he’s far less ridiculous that any number of assertions about Atlantis or lizard blood you can find in Ignatius Donnelly or David Icke. In this way, The Poems and Teachings is what we might call double secret weird. It’s weird that anyone would try to pass off poems (none of which are even close to being sonnets, of course; why would a Bantu write a sonnet? or a “hiaku” for that matter?) as the occult wisdom of an occluded king; but it’s double secret weird that the person doing the passing is a soldier-of-4chan edgelord whose avowed goal is to “drive liberals crazier than they already are.”

Imagine if the big gospel secret in Holy Blood, Holy Grail had been Life’s Little Instruction Book, and then you learn the book had been put out by South Park. No part of this sequence makes sense!

—Where can I read this book?: You just have to buy a copy, I guess.

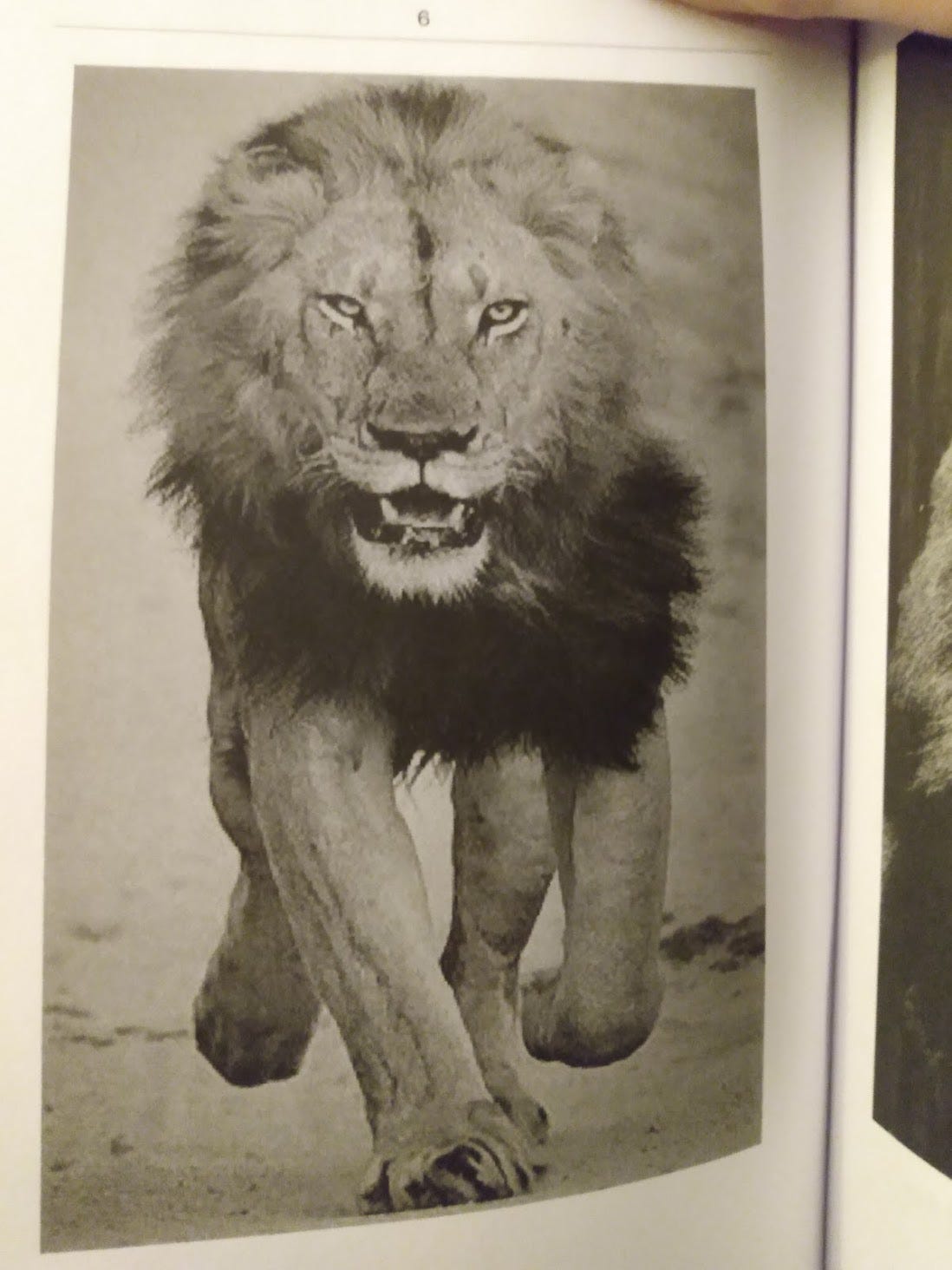

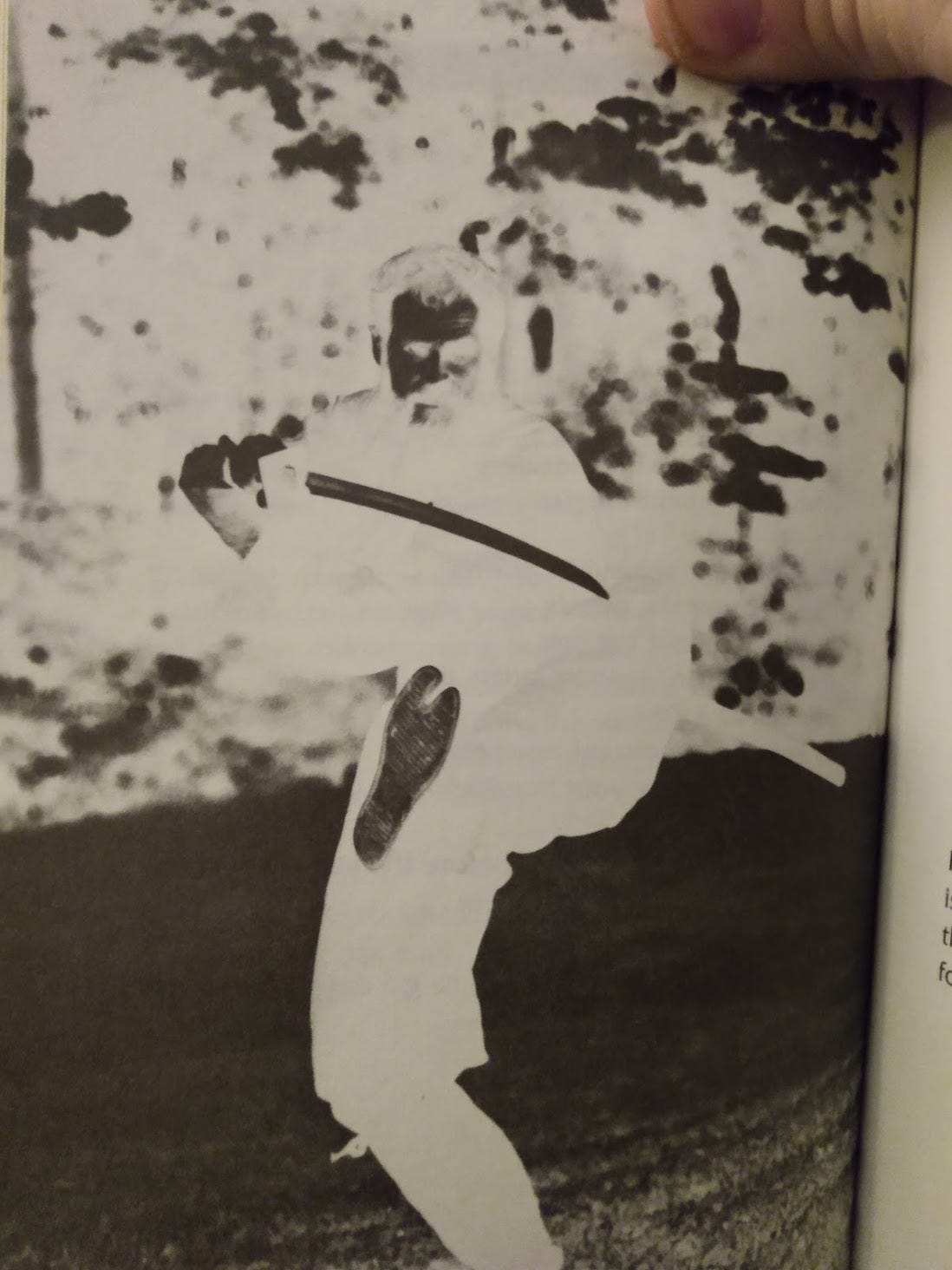

•Wisdom from the Ninja Village of the Cold Moon by Stephen K. Hayes (1984).

Stephen K. Hayes was “the first American ever to become a personal student in the home of the grandmaster of ninjutsu” (he says). In one sense, his book, Wisdom from the Ninja Village of the Cold Moon, is a bunch of ninja-themed poems illustrated by ninja-themed photographs; but his introduction explains that it is much more than that. Ninjutsu (he states) is nothing less than the last surviving vestiges of ancient wisdom that originated in (he alleges) Atlantis. Persecuted by those who feared or desired these “mystic teachings of the forbidden secret knowledge,” ninja were forced to develop their patented blend of secrecy, sneaking, and violence just to survive. Gnomic extracts of this secret knowledge are encoded on a “scroll of ultimate knowledge” possessed by “every ninja clan,” and Hayes has in this book offered us “an imaginative rendering” of what part of one of these scrolls might look like.

That’s all great! And unlike Obimingo Oboginimi, Hayes delivers! I’m not sure how good these poems are as poetry, but as ninja wisdom, they are amazing!

The ninja’s consistent observation of

the universal laws

must take precedence

even over the dictates of the heart.

Although the Village of the Cold Moon is (he says) fictitious, these photographs of ninja doing ninja things must’ve been taken somewhere.

Cold Moon has been my constant companion over the last thirty years or so; of all the weird books, this is, although clearly not the best, still my favorite. I have utterly failed to live up to its teachings.

The hysterical pour through the front gate

in wild pursuit

overlooking the intruder

who calmly sits among the rocks

in their very own courtyard.

—Where can I read this book?: You just have to buy a copy, I guess.

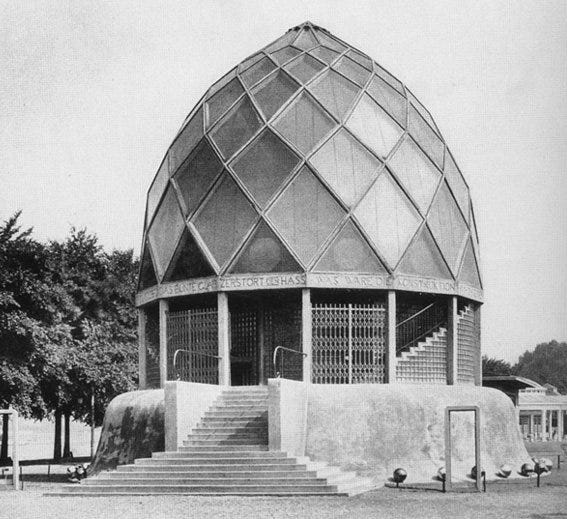

•Glass Architecture by Paul Scheerbart (1914).

Paul Scheerbart often didn’t “mean it,” in that many of the books he wrote are straight-up fiction; but sometimes he “meant it.” He staged a hunger strike to protest the advent of WWI, imbibing nothing but whiskey, and he meant it! Paul Scheerbart, 1863–1915.

His 1910 novel The Perpetual Motion machine is an apparently straightfaced scientific account of the construction of a perpetual motion machine, with plenty of diagrams. I assume it’s a novel, insofar as no one could be nutty enough to believe these ever-shifting diagrams could actually produce, you know, perpetual motion. But then there’s an equally nutty book like Glass Architecture, and that time I think Scheerbart meant it.

If Glass Architecture is not a novel, then it must be a manifesto—a manifesto calling for every building everywhere to be rebuilt, abandoning hated wood (“wood, because of its impermanence, is not an impressive material”) in favor of a schema of doubled walls of colored glass, with lighting fixtures in between. Guaranteed to follow is a utopian society in which all anyone ever thinks about is glass architecture. In the glassy future, “people will travel only to learn about a particular type of glass art and possibly bring it home”; furthermore, “one may also assume that nine-tenths of the daily press will report only on new glass effects.” Nine tenths, ladies and gentlemen!

Utopian, and I (and he) mean it! Upon the triumph of glass architecture, “we should then have a paradise on earth, and no need to watch in longing expectation for a paradise in heaven.”

Scheerbart is a Modernist, so of course he pingpongs between 1. complaining that fuddy-duddy architects are resisting his glass innovations out of mere hidebound superstition and 2. crowing that glass architecture is sempiternal and the final innovation necessary for human felicity. Are there a lot of bossy rules we will all have to follow to make Scheerbart happy? Of course there are a lot of bossy rules we will all have to follow to make Scheerbart happy! “Inside the glass house, too, wood is to be avoided; it is no longer appropriate. Cupboards, tables, and chairs must be made of glass if the whole environment is to convey a sense of unity” (v. important!). I hope you don’t like art, because “pictures on the walls are, of course totally impossible.” Scheerbart suggests bas reliefs instead, although obv. mere art in the realm of glass architecture is de trop.

Such thought inspired one (1) glass building, Bruno Taut’s 1914 Glass Pavilion—Scheerbart and Taut had been planning glass architecture long before the publication of Glass Architecture—but tragically Scheerbart died before he could see the world transformed into a paradise of glass, which it never did, and anyway I like pictures on my walls.

All modernist utopias are secret hellscapes, but when they never get beyond one book and one (long demolished) building they are at least only the blueprint for a hellscape, and those can be forgiven.

—Where can I read this book?: Translations of this and several other works by Scheerbart are collected in Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader (U Chi P, 2014). Someone uploaded a pdf of a translation here. The original German book is of course public domain.

•The History and Adventures of an Atom by Tobias Smollett (1769).

Tobias Smollett is easily the most canonical author to appear in this catalog of weird books, although perhaps his specialty—picaresque novels where ten different unconnected things can happen to a character in the space of a couple pages—is not so in favor to current canoneers. His longest book, The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle, is padded out by an extra hundred pages (plus) by the inclusion of a “Memoir of a Woman of Quality,” a book-length anonymous autobiography by a different writer (and in a different style—no one can write quite like Smollett) passed off as the musings of one of the novel’s many characters. Pickle also includes a scene (excised in the second edition) in which the main character bores holes in his aunt’s chamber pot. A good time all around.

But none of that is weird in the least when compared to The History and Adventures of an Atom, by far the weirdest book by any major writer of the eighteenth century (sorry, Sterne!) and probably also the nineteenth. It is narrated by an immortal atom (“one of those…constituent particles of matter, which can neither be annihilated, divided, nor impaired”) living, for the moment, in the pineal gland of a London haberdasher. The atom dictates a story to the haberdasher, who, under threat of pineal torture by a testy atom should he fail, writes it down. And this is the book they produced.

All of that is weird enough. But the story the atom chooses to tell is the story of way back when he lived in the rectum of an eighth-century Japanese politician named Fika-kaka (few of the Japanese names are very…plausible). Fika-kaka’s anal fixation is extreme, and he is barely introduced before he’s applying to his itchy anus a vile crème which he then lets a tomcat lick off. Ass-kissing, which is treated as the conventional political metaphor, is also treated as a literal event, and described in terms both repulsive and so pedantic as to be almost unrecognizable.

E.g.: “The osculation itself was soft, warm, emollient, and comfortable; but when the nervous papillae were gently stroaked, and as it were fondled by the long, elastic, peristaltic, abstersive fibres that composed this reverend verriculum, such a delectable titillation ensued, that Fika-ka was quite in raptures.”

It quickly becomes clear that the only person more anally obsessed than Fika-kaka (Fika-ka is just a nickname, or a typo) is Tobias Smollett. The first fart joke in the novel appears in the second paragraph of the editor’s preface; it will not be the last.

Japan is, at this time in its (almost 100% fictional) history, at war with China, and the narrative that follows is the story of this war, as viewed through the lens of Fika-kaka’s butthole. As is clear from the brief excerpt above, the lens is one that is over-academic; chock-full of classical allusions and phrases in Latin and Greek, as well as precise philosophical, scientific, and especially medical jargon; in a word, Rabelaisian. The atomic narrator knows his Rabelais well, and is not afraid to acknowledge his master quite overtly; the atom is very literate. At one point (our narrator reports) as food becomes scarce in Japan, an “orator” named Taycho “contrived a method to be spared the expense of solid food…He employed his emissaries to blow up the patients à posteriori, as the dog was blown up by the madman of Seville, recorded by Cervantes. The individuals thus inflated were seen swaggering about the streets, smooth and round, and sleek and jolly.” You’ll notice the atom remembered his Don Quixote; and perhaps the whole scene is reminiscent of something from Jonathan Swift.

A war between Japan and China a thousand years ago…this would all be a pretty arbitrary tale for an atom or an eighteenth-century novelist to tell; except it is all an allegory. Japan is England; China is France; Taycho is William Pitt (the Elder); Fika-kaka is the Duke of Newcastle (whoever that is). The whole war is the relatively contemporary Seven Years’ War transferred to the east coast of Asia. Korea is Spain. Cambodia is Sardinia. Various “keys” to the book were published even in the eighteenth century, not all agreeing with each other.

Smollett didn’t contrive this abstruse allegory just to be weird. He was afraid of being charged (not for the first time in his career) with libel—not an unjustified fear, considering he had characterized King George II as a reincarnation of a goose fart, “rapacious, shallow, hot-headed and perverse; in point of understanding, just sufficient to appear in public without a slavering bib.” That’s not something you’re supposed to say about the king; but of course technically Smollett said it about the Japanese emperor Got-hama-baba. Just to be extra safe, though, he published the book anonymously, and while living abroad.

The resulting volume is challenging to read unless you know an awful lot about the Seven Years’ War. You have to keep track of one set of utterly ridiculous names (e.g. Sti-phi-rum-poo) and match them to a historical personage you’ve probably never heard of (in this case the Earl of Hardwicke). And the whole time the insufferable atom can’t stop going off for page after page on tangents about (for example) the etymology of abracadabra and its relationship to the myth of St. George. The book (>400 pp. in its first edition) could stand to be shorter.

But for sheer scatological vulgarity, if that’s what you’re into, Atom is unmatched outside of de Sade. And occasionally Smollett straight-up gets a good gag in. Yam-a-Kheit (James Keith) dies saving Brut-an-tiffi (Frederick the Great) from his own incompetence, and Brut-an-tiffi, after the manner of emperors, immediately blames not himself but his savior Yam-a-Kheit. Smollett’s gloss on the situation is delightful:

“’Tis an ill wind that blows nobody good:—the same disaster that deprived him of a good officer, afforded him the opportunity to shift the blame of neglect from his own shoulders to those of a person who could not answer for himself.”

Mostly poop and Pythagoreanism, though.

—Where can I read this book?: Here and here, although you might want to get the version edited by Robert Adams Day (U Geo. P, 1989), which has copious notes to make sense of everything; and also does not employ the distracting long ſ.

Weird Books part 2

•Nice Girls Do…and Now You Can Too! by Dr. Irene Kassorla (1980). What “nice girls do,” it turns out, is have orgasms, and Dr. Kassorla is here to give you one as well (whoever you are). Turns out, if you’re having trouble achieving orgasm, it’s probably because of your inhibitions, which I suppose makes sense, although since every patient in the book sp…

Thank you for telling us how weird people are. I sometimes mix 'literature" into my regular social thought and economics Substacks and I am surprised when readers cannot seem to distinguish the two things. Maybe they are right. Maybe it is not all that clear at all. Lately I am getting confused myself. Writing nonsense is quite appealing and sometimes quite difficult to sort ot from the serious stuff. So why am I surprised that other people have trouble distinguishing?

Someone needs to record The History and Adventures of An Atom for Librivox, but I am not the man.