Weird Books part 2

In no particular order, five weird books you may enjoy; brief reviews.

•Nice Girls Do…and Now You Can Too! by Dr. Irene Kassorla (1980).

What “nice girls do,” it turns out, is have orgasms, and Dr. Kassorla is here to give you one as well (whoever you are). Turns out, if you’re having trouble achieving orgasm, it’s probably because of your inhibitions, which I suppose makes sense, although since every patient in the book speaks like an overenthusiastic clinician, you’d think the first hurdle was cleared. Less plausible is the fact that these inhibitions inevitably prove to have a unique source, such as a “parent’s negative facial expressions” when you were “less than a year old” (a memory recovered by patient Amy when she was a married woman). It all goes back to childhood. Like a Hollywood parody of a Freudian, Dr. Kassorla will seek all solutions in your prepubescent sexuality.

I’m going to go ahead and give you Kassorla’s surefire orgasming technique. What you need first, is to recover (as Amy did) some memory from your childhood—a slightly naughty, innocently sexy memory. Young Doug peeped through a crack in a door to watch his mother’s friend undress. Young Louise snuck a peek at her naked grandfather. Young Frank accidentally walked in on his naked mother. Poor young Brenda had to make do with ogling the outline of her not-even-naked brother’s penis in his tight swimsuit. Young Mark merely breastfed (like a normie) but fortunately was able to recover memories of himself “as an infant” suckling away so that works. Kassorla helpfully suggests other scenarios for the puzzled, including two separate possibilities that involve peeping at naked family members “through the keyhole,” a straight-up Freudian primal scene, and, of course, “seeing your dog lick that long, red thing of his.”

Now that you have that memory, here’s what you do: Wait until you’re having sex and then start monologuing about the dog penis (or whatever your thing is). “The more I talked, the more orgasms I felt, the more orgasms I wanted, and the more orgasms I was able to have” (enthuses Harriet).

There are a lot of case studies and testimonials, but that is seriously the trick. A mid-sex encomium about your dog’s (or your brother’s) willie. Although Kassorla does encourage her patients to let the sex speeches take them into weird places if need be. “Both of us began using street jive like Hell’s Angels,” reports Sharon (of herself and her husband); a great time. Nevertheless, Kassorla cautions, “avoid discussing actual sexual experience that you had after the age of twelve.”

For advanced students there is a special kind of orgasm called the “maxi,” so overwhelming and intense that Kassorla describes it over four vague but enthusiastic pages.

I leave the testing of these hypotheses to the reader. I assume, as with all sex advice ever, they work for some people, and the only question is how large that slice of some is. Even though I doubt this book will be broadly useful, I still love it, and I love it, in part, because of passages like this one:

“I was working with Colleen in my Monday night group. She was just discussing her four-year-old daughter’s sex play with a neighbor’s child. Jeanne, another group member, interrupted Colleen with some material she had suddenly unblocked from her own childhood…”

And then follows Jeanne’s rather pedestrian reminiscence. This is an amazing passage! The idea that Dr. Kassorla has people come to her group sessions week after week, desperately trying to remember seeing a naked cousin; that Colleen is presumably bursting with excitement to talk about a memory she is husbanding away for her own daughter, who will need it when she is older and wants a “maxi”; that Jeanne rightfully views Colleen’s proxy contribution as bogus and grabs the conch to get her own two cents in; and especially and overall that Dr. Kassorla starts her anecdote with (essentially) “I was working, dear reader, with Colleen, who is actually an ancillary figure in the anecdote, and in a couple of sentences I’ll get to Jeanne”—that passage has haunted me for the last ten years, ever since I first read this book, and I’m so glad I got to dig it out again to write this review.

I am far too classy to make the obvious orgasm joke here.

—Where can I read this book?: Should be readily available used.

•Translations, Literal and Free, of the Dying Hadrian's Address to His Soul edited by David Johnston (1876).

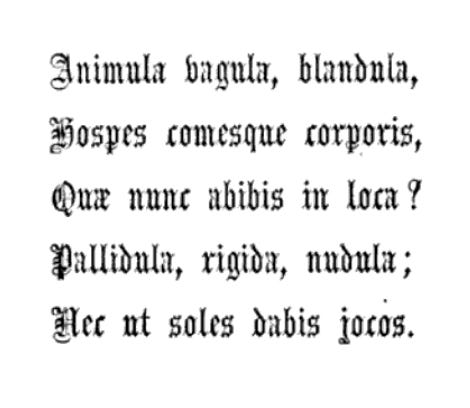

This book contains seventy pages of translation, translation of a five-line poem. That in itself is an astonishing feat. The five-line poem is one Hadrian improvised (?) on his deathbed in the year 138. It runs (in Latin):

Animula vagula blandula

Hospes comesque corporis

Quae nunc abibis in loca?

Pallidula rigida nudula

Nec ut soles dabis iocos.

This roughly correlates to (I give the translation of the late Edwin Palmer):

Little, gentle, restless soul,

Comrade of my frame and guest,

Whither wilt thou now away?

Cold, stiff, naked, and no more

Jest as thou wert wont before.

(The book separates out translations by the now-dead from those by the still-living, all of whom presumably, 150 years later, are also now dead.)

It correlates, I repeat, only roughly, of course, because translations are difficult; because Hadrian’s brief text is particularly difficult; and especially because Hadrian’s brief text is extremely weird.

What follows a full-page presentation of H.’s original are 116 translations, mostly into English but also in Greek, French, German, etc., mostly contracted especially for this volume, and mostly not by “real” (i.e. famous) poets. The idea that 116 very similar five-line poems might be an exercise in “monotony” is floated as early as…page one of this book. Yes, it is, in fact, literally the first sentence.

(Not literally page one, though; like many books, this one starts on page five.)

All of these translations (I mean those in English; I’m not here to judge the one(s!) in Gaelic (!)) are competent. None is particularly felicitous. Everyone seems more or less aware of the problem. Edwin Palmer from the piece above is quoted as fretting:

“I have not attempted to preserve the iambic rhythm, because so wonderful a lightness is given to it by the use of many short syllables in the first and fourth lines, that I despaired of approaching its effect.” Etc. Etc.

His complaint goes on, but you could boil it down to “I despaired.”

And yet, even though they know they are failing, the translators simply fail again and again, 116 times in a row. Hadrian defeats them.

Spirit, thou wanderer loveliest,

Guest and companion of this frame,

To what new regions tendest thou ?

Pale, stark, thrown off thine earthly vest,

Thy wonted quips all ended now.

(As per E.S. Pearson. This book may have the highest proportional appearances of the word “wonted” of any text in history.)

The problem, if I may be so bold as to nitpick a hundred-plus people who presumably knew more Latin than I do, is that Hadrian wrote a weird poem, and no one in 1876 was capable of writing a weird poem. The whole reason the poem is famous in the first place—aside from the fact that Hadrian was a Roman emperor, granted—was because the poem is ostentatiously bizarre. “Animula vagula blandula” is a weird opening line. Critics (this volume’s generous introduction makes plain) argue over whether Hadrian was being flippant. “Anima vaga blanda” would be the “normal” way to phrase it, but not for the last time in the poem, Hadrian tacked on a bunch of diminutives. The result is strange. For two thousand years people, who haven’t always liked the poem, have had to grapple with the poem. It imbalances the reader in a way that classical verse does not tend to do. It’s practically begging for a Modernist interpretation, which in 1876 it of course is not going to get. Gerard Manley Hopkins would have done something interesting with it, but if 1876 is not too early for him to do something interesting it is nevertheless too early for him to be invited to do something interesting. And so no one does. Pound and Eliot riffed off it, but if any Modernist has translated Hadrian’s address to his soul, they didn’t tell me. And so we are left with an expansive collection of failures.

So, to join the fail brigade, I present below my own groping attempt, complete with gauche nod to Hopkins, at five lines of interesting. I’m not happy with it, but I guess I’m happy enough that I floated it out there to you, the cruel and carping public, so make of that what you will.

Darling rambling spiritling—

Body’s buddy, guest-ghost—

Whither will you drain, so very

Cold and nude and pale?

…No jokes for you now!

—Where can I read this book?: Available for free, here for example. (Archive.org’s version has the pages out of order?)

•Roaring Guns by David Statler (1938).

I assume, in this fallen world, that Roaring Guns is a hoax, a cunning fraud like O Ye Jigs & Juleps!, but I don’t want it to be, so I’m not doing even one second of research. I’m going to pretend the whole thing is real.

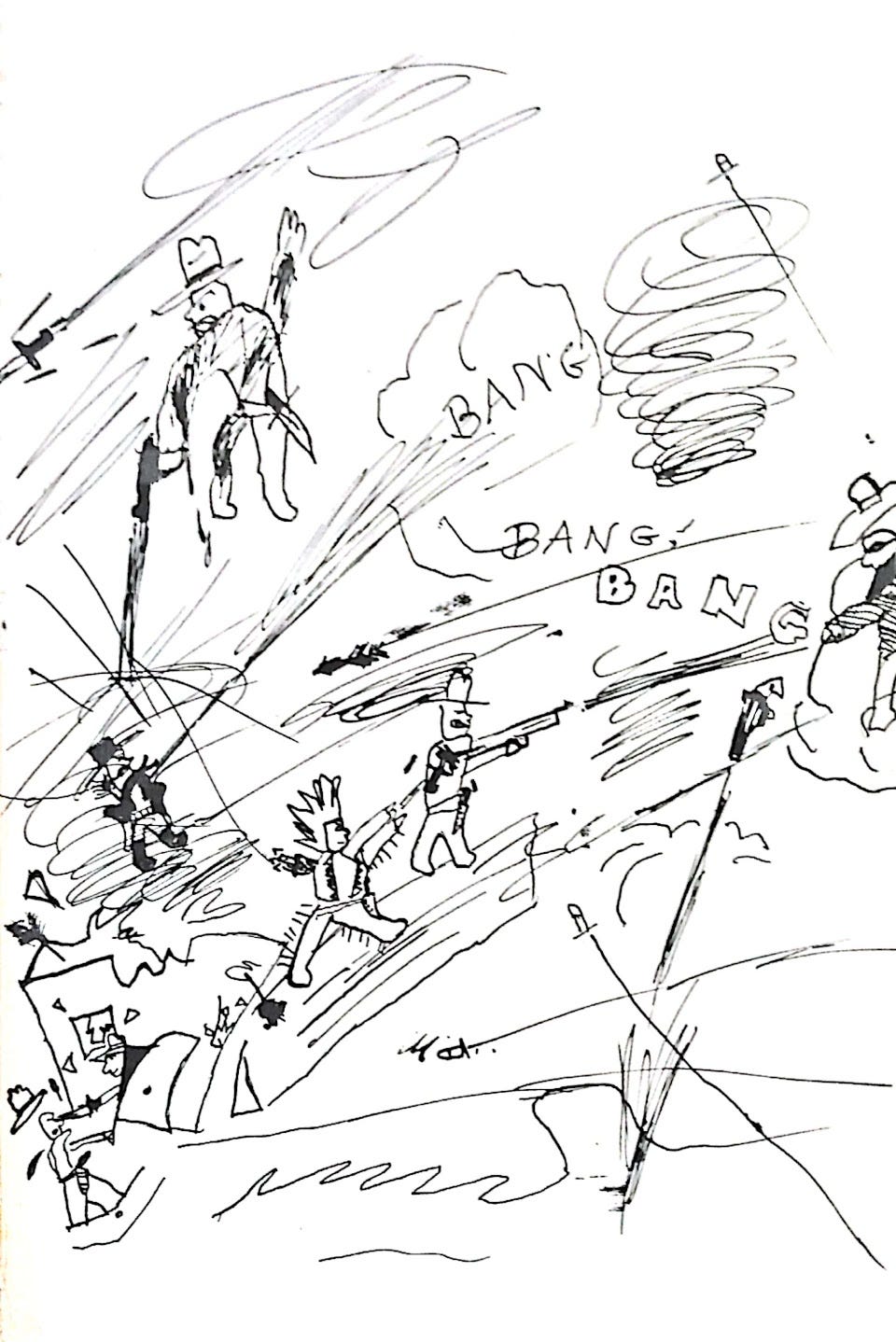

Ostensibly, Roaring Guns is a fiction (starring silent-movie cowboy actor Tom Mix) written and illustrated by a nine-year-old boy. Rather than an exercise in Axe Cop absurdity, what follows is a passing imitation of a Western pulp, but written with charming naivete.

“When he regained his senses he was in a small room with a man standing in front of him aiming a gun at him. Tom remembered that he had a gun in his pocket, and so he said ‘Care if I get a match’ and without waiting for an anser he pretended to get a match. But he really got his gun which was not showing. They did not search him. As he shot one bandit he swung his fist into the other ones face knocked him backwards.” Etc. (and sic throughout).

What is especially interesting is the fact that the young author has clearly read enough pulps that stock phrases of competence keep creeping into the narrative.

“Tom’s gun flashed to his hand.”

“Nothing broke the stillness except a low moan.”

“He snapped out his gun. Tom did the same. They cracked at the same time and the chief sagged against the door.”

But mostly the pleasure comes from the times when young David’s analysis of pulp only gets him halfway across.

“One day Tom went into a saloon and asked for a glass of water. Suddenly the door of the saloon came off with a splintering crash and twelve men with guns still smoking in their hand enterd the room.”

As Statler says: “Tom had an exciting adventure that time. Now let us stop and rest before we read.”

—Where can I read this book?: Buy it used; semi-collectible.

•The Arthuriad by John d’Arcy Badger (1972).

Let’s say in 1972 you had a glorious vision for a complete revolution in societal consciousness. This vision is explicitly tied to the Age of Aquarius, but explicitly divorced from any of the characteristics we associate with the youth movement. In fact it is divorced from just about every mass movement of the day, being explicitly anti-capitalist, anti-socialist, anti-communist, and anti-fascist. How would you persuade people to join your sui generis spiritual movement?

If you’re John d’Arcy Badger, you might want to write fifty-six sonnets about the moral virtues of King Arthur. And then, since sonnets can be a little abstruse, you might add fifty-six free-verse commentaries explaining everything. Divide the whole thing up into six cantos, and you’ve got The Arthuriad.

Perhaps because 1972 was a different time and perhaps because the philosophy of Arthuriana is slippery, it can be difficult to pin down the politics of the book. Take these progressive-friendly verses:

We need special hospitals for the violent:

the criminals, the wife and child beaters,

the totalitarian terrorists and apologists:

a hospital in which, openly, without cruelty,

they cane be kept while their personalities

are remoulded into gentleness: nothing more.

They should not regain freedom

til they threaten no one in reality.

And if there still is doubt,

they should live in freedom on an island:

free except to leave it.

And compare it with this familiar conservative outrage:

There is a hidden establishment deeply entrenched

in much of education and the mass-media:

faculties of political science

where it pays to be a Maoist,

teachers’ colleges where the dears

are well drilled in socialism,

padded over in the windbag words of the left liberal,

and simulated news events to stampede the journalists

lest they be labelled with unfashionable tags.

These aren’t even moderate stances! “Simulated news events” is a play right out of Alex Jones; forcibly reprogramming “apologists” is, in turn, straight Mao.

There’s probably a key to this apparent incoherence, which is that Badger is a Romantic Christian populist, supporting the proletariat (his term) but unimpressed with outsiders, which is to say everyone in this fallen world. Also, he’s Canadian?

Who stays true to the trinity

can build one to infinity.

But we’re not really here to cipher out Badger’s complicated politics. We’re here because Badger expressed his complicated politics in sonnets about King Arthur!

…We swear that Truth, our word,

will force foemen to believe us.

We scorn Right-wing reward.

We let not the Left deceive us.

We pledge our souls in troth

to live by Arthur’s oath!

Unfortunately—and this is what keeps this book from being one of the all-time great works of outsider literature, as well as from converting me personally to whatever it’s aiming at—sonnets are difficult to write. Probably zero of the fifty-six fourteen-line poems in this book are technically sonnets. Their meter tends to waver crazily between trimeter and tetrameter. Each sonnet uses the unorthodox rhyme scheme ABBA CDDC EFEF GG. None of this is fatal, and many works (Eugene Onegin, etc.) have toyed playfully with the sonnet form. But writing a sonnet is hard, and writing a good sonnet is even harder, and probably zero of the fifty-six almost-sonnets are, as poetry, good. Most readers will probably find more to enjoy in the free-verse commentaries, with their splenetic jeremiads against Freud, elitists, hippies, etc. It’s always interesting to see what a square from 1972 thought of hippies, and how often figures like Badger (or Al Capp) focused on their unkempt appearance.

…a thing

with the look of the tarantula

and the smell of an outdoor toilet.

This calls others pig?…

The Arthurian [of course] does not just differ

He opposes vigorously.

I added the “of course,” of course. The goal, for Badger, is to return to the values of the Round Table, or a Romantic conception of those values.

His sword, long in the lake,

glitters unchanged, Awake!

I somewhat cruelly criticized Badger’s skill as a versifier, but the pithy, loose catchiness of that last-quoted couplet points towards the exception. The final GG of each sonnet, usually a self-contained thought, often offers something that points towards beauty.

The scientist had best

lay Frankenstein to rest.

Next in evolution:

life-style revolution.

The lust of Lancelot

the realm to ruin brought.

Unbeatable, their end was sad:

betrayed for God by Galahad.

Had the rest of the sonnets been as strong as that last couplet (easily my favorite in the book), I would have been converted; would have drawn the metaphoric sword from the metaphoric stone; do—I’m not actually clear on the next steps. But I would have done them!

Except I was not converted and didn’t.

—Where can I read this book?: You just have to buy a copy, I guess.

•Shadows from the Walls of Death by R.C. Kedzie (1874).

“The poisonous nature of the paper of which this book is made will suggest to you the propriety of not allowing it to be handled by children” is one of the most wonderful paratextual warnings ever to accompany the title page of a book. Forget the poisonous books of Dorian Gray (merely metaphorical) or Name of the Rose (merely fictional)—in 1874 Dr. R.C. Kedzie produced a literal actual poisonous book, Shadows from the Walls of Death. Only five copies survive. You probably should not touch them.

Far from being a Bond-villain murder weapon, Shadows was actually part of a galaxy-brained plan to prevent people from being poisoned. In the nineteenth-century, wallpaper pigment was frequently made with arsenic, and although conventional wisdom was that such pigmentation was fine provided you did not lick the wallpaper, Kedzie argued that arsenic dust was in fact constantly drifting off the wallpaper and into the slowly sickening and even dying schmucks who lived in these wallpapered rooms. As Kedzie points out, “The danger for equal doses of the poison is vastly greater when it is inhaled than when it is swallowed, for we take food only at distant intervals, while we breath[e] continuously.”

After a brief, sober introduction, Kedzie presents us with the meat of the book, which is page after page of toxic wallpaper. This is an art book designed to raise awareness of the dangers of art. The green hues are lovely; arsenic is apparently an attractive pigment.

—Where can I read this book?: For Pete’s sake, read it digitally! Here, perhaps. Doubtless, some of the brilliance of the color is lost this way.