Anatomy of a dungeon

I’m talking about Dungeons & Dragons dungeons, of course. What else would I speak of?

[My urban fantasy novel Immortal Lycanthropes, the one Cory Doctorow called “perfectly wonderful and wonderfully perfect,” is available starting now for $2.99 on (shudder) Kindle! You can get the regular or a special sanitized version with all (v. few) references to sex or drugs excised so you can show it to your mom. I’m proud of this one! Please check it out!]

Anatomy of a dungeon

I’ve spent a lot of my life playing Dungeons & Dragons, and a lot more of my life thinking about the dungeons thereof. When I say dungeon, I mean a place where adventurers can face peril and gain treasure, or perhaps even merely a place with a map and a key, suitable for gaming in. I guess the local castle or thieves’ guild could count as a dungeon, but let’s focus a moment on cooler dungeons—ancient ruins, underground tunnels, and labyrinthine caverns. You know the kind of place I mean.

Good dungeons are exciting and playable and all that, but a dungeon is also (like almost everything) an esthetic object. I love to read through a good dungeon! And I want to talk here about what makes a good, an esthetically good, dungeon esthetically good.

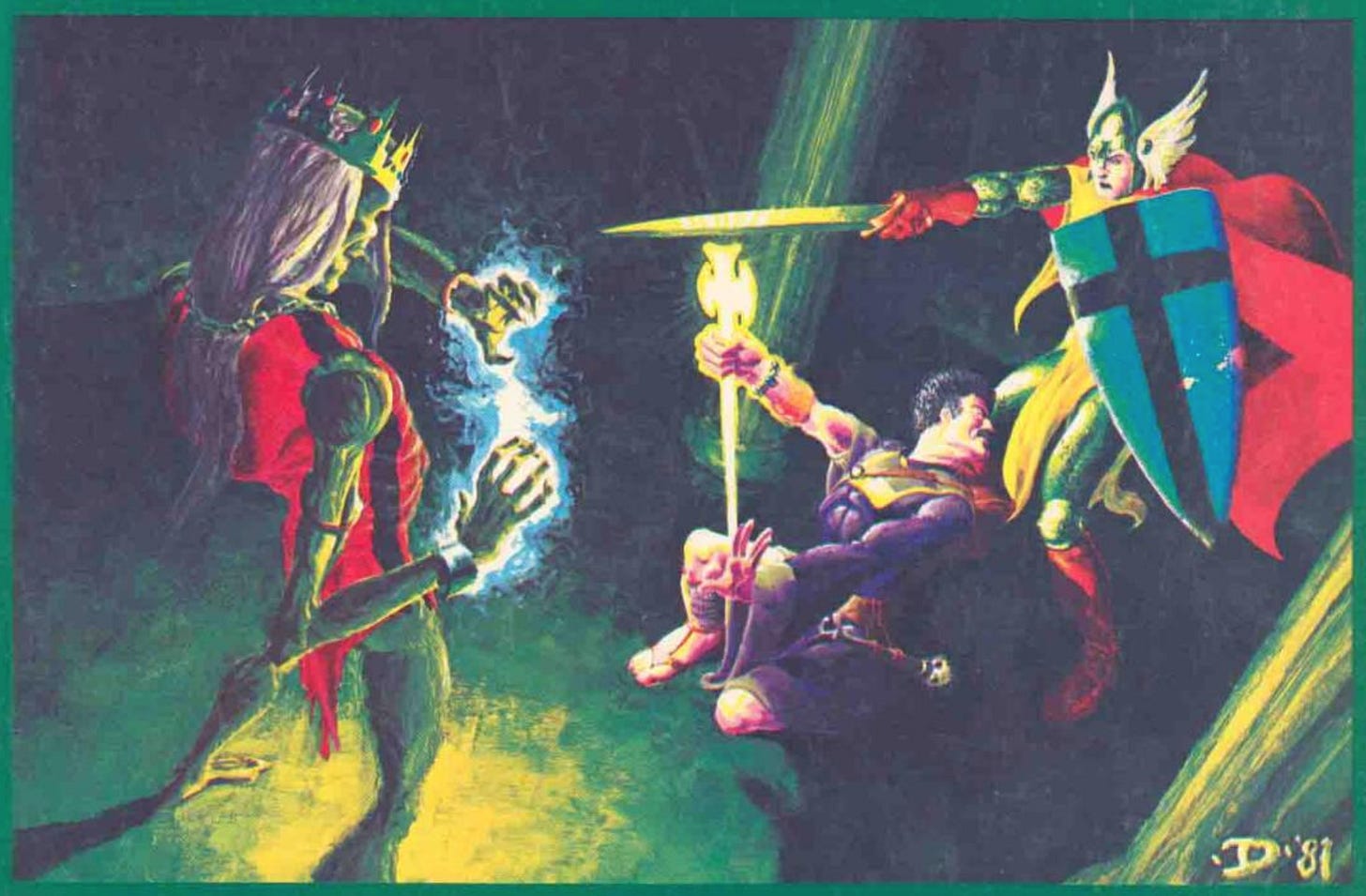

None of what I’m going to say is particularly radical, or even novel—I learned it all by reading old TSR modules, after all! Only briefly will I point out that much of what makes a good module (interesting NPCs, say, or Erol Otus art) is somewhat orthogonal to what makes a good dungeon.

A good dungeon should have 1. an origin, 2. a history, and 3. an ecology. You can get along without all three (a natural cavern might have no real origin, a dungeon built yesterday might have no history, and Tomb of Horrors—well, that place may lack an ecology), but you probably need two out of three, and all three is the norm.

And let us keep in mind: A good dungeon should be many things (exciting, surprising, etc.), but for esthetic reasons, a good dungeon should also be legible.

The origin

This is what I mean by the origin of a dungeon: Someone has to have built this thing, and doubtless for a reason. As I said, a natural cavern skimps on this section, but a purely natural cavern is more or less a wilderness adventure with a roof. Usually, someone decided to appropriate these caves for their own use, and it behooves the game master to determine who and why.

You know the classic reasons: A wizard built this dungeon to house his treasure (Ghost Tower of Inverness). A ruler built this dungeon to be his tomb (Pharaoh). A cult built this dungeon for the performing of strange rituals (Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun). A sorceress built this dungeon to house something for later access (Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth). A giant built this dungeon to live in (Against the Giants). A demi-lich built this dungeon to lure adventurers to their doom (Tomb of Horrors, at least in the Labyrinth of Madness retcon).

Let’s imagine (I’m winging it here) that a benign wizard, possessing an evil artifact he cannot destroy, hides said artifact in the center of the impenetrable labyrinth of doom he constructs for the purpose. A hypothetical origin.

Obviously, it’s possible for a dungeon to persist quite simply in fulfillment of its intended purpose (such as a hill giant chief’s steading, say), but I prefer dungeons to be ancient in their construction, and of origin most occluded and obscure. The basic shape (or “bones”) of the dungeon, its neglected nooks and crannies, and perhaps even a sealed-off subbasement will give hints to the dungeon’s original purpose, but much of this purpose will be overwritten by the perpetual noise that is its…

…History

A building rarely perseveres forever in its original intent, which is how Limelight got set up in a decommissioned church. Imagine in the Middle East (in our Earth Prime) an ancient Semitic pagan temple that got converted into a Hellenized Greek pagan temple, later rededicated as a Christian church, and finally rerededicated as a mosque. Bet it happens all the time, and it may have been a stable or a storeroom somewhere in between.

Gary Gygax’s Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun provides a canonical example: As soon as the Tharizdunites move out of their forgotten temple, a bunch of norkers move in. The norkers don’t care about worshipping Tharizdun—they just want a place that keeps the rain off.

This is, I think, of the greatest importance to crafting a satisfying dungeon: The history of a dungeon should exist against, despite, or in ignorance of its origin. Often the top level or a dungeon—I mean, the one most easily accessed by people walking in off the street—is crammed full of humanoids who have set up their own little fiefdoms, Keep on the Borderlands-style. Perhaps the humanoids have discovered a level-one treasure room (left by a previous tenant), and are living high on the hog of its gold pieces. Perhaps they hear deep moans from below their feet, and have come to regret building their home in a dungeon the origin of which they know little of.

When I say “a previous tenant” I don’t necessarily mean the original builder. Wave after wave of settlers may have come in and displaced each other sequentially. Perhaps each wave has been driven down into a progressively lower level of the dungeon. Perhaps they have left nothing behind but their graves (and undead?) and their own slight modifications on those original “bones.”

If a dungeon was built millennia ago (as a good dungeon should be), then dozens of waves of inhabitants are not only possible but likely. The result might be illegible (which, recall, a good dungeon should not be)—but not every wave needs to be important or leave its mark. Two or three could, though, and quite legibly. Lizardmen carve their inscriptions over the defaced inscriptions of hobgblins. Cloud-giant sized sarcophagi are denuded of their bones, and kobolds then interred therein instead, twenty of them lying side by side like railroad ties.

Previous adventuring parties are absolutely a possible part of a dungeon’s history. Their mangled corpses can provide treasure or (from manner of death) hints about what kind of creature lurks around the corner. Perhaps there are prisoners, still alive, in iron cages in the kitchen. Perhaps they’ve been changed into wights, harder to hit or turn now, what with the magic armor their undead forms still wear.

As an example of a slightly baroque but still (I think) legible dungeon history, I’m going to spin something below. This is based off our labyrinth of doom example. If you don’t care to read a bald summary of a thousand years of fake history, skip this part.

So this benign wizard wants to hide an evil artifact, remember? Now, I suppose it would make sense that the benign wizard would (for extra security) construct his labyrinth of doom with no entrance…but imagine a kingdom of dwarves, canonically prone to digging too deep, managing to breech its walls quite accidentally. Attracted to the inlaid gems used to craft the enchanted sigils designed to stave off detection magic, the dwarves incorporated the larger (and outer) corridors of the labyrinth into their underground kingdom (this creates a kind of double dungeon, with a first level that is regular dwarven halls, leading into a realm with older stonework). Pry out those gems, dwarves, and…

Soon, evil cultists desperate to reclaim the artifact lost for centuries (and now locatable because the nondetection sigils have been compromised), have moved in and with their summoned demons defeated the dwarves. But despite their blood rituals and thaumaturgy, they could never unravel the riddle that would gain them access to the inner levels of the labyrinth, and so eventually they all died of old age, disappointment, or betrayal / cultic infighting. They left behind only innumerable location-bound extraplanar servants (now bored and aimless), horrible pentagrams, vandalism, and that legion of dwarven undead they raised.

Over time, a crew of tinker gnomes could well move in to the dwarven halls above, only to fall in turn to a large swarm of wererats (or something similar). The gnomes’ automata wander up and down the levels of the dungeon endlessly, occasionally still dispatching an unwary ’rat.

Rumors of the dungeons below the dungeon have brought various adventuring parties, seeking passage through the upper level. The ’rats used to permit adventurers freely (or with a small gratuity) to go through their lair to die in the deeps, whereupon the wererats would send some furry little rat allies down to plunder the corpses of all gold and magic. At one point the ’rats acquired thereby an iron flask with a marid in it, and a combination of marid-hostility and bungled wishing for renewable fresh water blew a raging river right through the heart of the ’rats’ domain. Unable to ford the torrent of water, they’re now trapped down there, on the wrong side of a river that intersects the only corridor “out”—trapped in a dwarven hall with no way to the surface and only evil below them, kept alive only by a magic item (rod of splendor or the like) and in perpetual fear it’ll run out of charges. (Or perhaps they can fish? I mean, they have a river.)

With the wererats locked in on the far side of the river, a tribe of gnolls has settled into the rooms around the entrance.

This gives us:

•Right as you enter: a dwarven subterranean palace populated by hostile gnolls.

•A hard-to-cross underground river with, on the other side, ravenous wererats bristling with magic items. This would still be in dwarven-dug tunnels.

•As you pass down the deepest dwarven tunnel, through which dangerous automata scamper, you enter the labyrinth proper. Here are the dwarven undead, the demons (left behind, probably bound to the labyrinth, and certainly hungry for blood), and perhaps a small group of miserable dwarves, long since mutated into derro or duergar thanks to the experiments of blood cultists, skulking in the shadows of a forgotten side corridor and adept at avoiding all (demonic) danger.

•And once you figure out the way in that the cultists did not, you are merely in the next level of a labyrinth specifically built to keep adventurers out. Traps and tricks again. Perhaps some golems. At the very heart a most dangerous guardian—a planetar, maybe, keeping its eternal vigil over the evil artifact, or alternately a tasked guardian genie riding on the back of a guardian daemon.

Interrogated gnolls might not know anything of the larger dungeon, other than they can hear wailing from beyond the river at the edge of their demesne. The wererats know (but will they tell?) about the history of the gnomish automata, about the marid-river, and perhaps they have a pretty good idea about the horrible blood cult below. The cult’s remaining demons know much, if they are cajoled to tell, about the dead dwarves, the cult, and the labyrinth. And of course everywhere in the labyrinth are DANGER TURN BACK signs in an ancient tongue, which you may interpret as you will.

This brings us to the hard part:

Ecology

It is probably impossible to make a dungeon ecology work, which is why very few intelligent bipeds choose to live their whole lives underground. The sun, it turns out, really helps keep an ecosystem viable. Fantasy ecosystems rarely make sense even outdoors, as there are always too many carnivores. (Count the number of lions appearing in the average Tarzan novel.) Underground only makes it worse.

But we’re supposed to try, right? Our job is to try to make sure every monster in a dungeon has 1. stuff to eat, 2. a place to poop, and 3. enough elbow room that they don’t go crazy. The third one won’t apply to ants, say, but it will to goblins or drow or what have you.

The easiest thing is to let the monster leave the dungeon to forage. Bats fly out of their cave every night, and so do vampires. The gnolls in our labyrinth of doom example are no problem at all. They can hunter-gather outside or rob caravans or whatever.

Things are more difficult deeper inside the dungeon. How does Moria get its food anyway? Light-shy funguses and subterranean rivers full of cave fish can provide some help here, as can magic. The river can also carry away the poop! Other potential latrines are just any kind of bottomless crevice or (my favorite) a hellmouth. For a thousand years these svirfneblin have been pitching their filth into a one-way portal to the abyss, and when the players have to interact with a demon, they are going to find that demon extremely incensed, not to mention filthy.

One good trick is to have the dungeon be at the end of a garbage chute—the garbage chute that foraging monsters on level one employ. Food waste (or, you know, solid waste) from an ogres’ stronghold could feed a lot of dungeon creatures. Perhaps access into the dungeon is only available through the garbage chute, a suitably disgusting entrance for adventurers (put an otyugh at the bottom!).

Or there’s always the old standby of an underground magical forest or garden providing food for all! Just a big cave with miraculous trees lit by a secret sun. I bet Ibrahim Ebn Abu Ayub had a subterranean garden; why can’t whoever built dungeon x? The point is, I don’t care how you do it, you just need to put something in to justify all the hungry umber hulks and beholders flitting about down in the deeps.

Xorn, of course, eat minerals, which are plentiful underground. Rust monsters eat metal. Ropers, it is implied, can eat many rocks. Etc.

It’s clear that early D&D play imagined an ecosystem build around adventurers. Mimics, trappers, lurkers above, and gelatinous cubes are all creatures that seem to have evolved in dungeons where hapless characters trundled through often enough that they could be a primary food source. Outside of one of those city-adjacent megadungeons where PCs line up to take a creaky wooden elevator down to their selected level, this doesn’t make much sense to me.

But of course, much of a dungeon exists outside of ecology. Much of a dungeon is just traps ’n’ tricks, but additionally you have gnomish automata, most undead, golems, living statues, elementals, animated furniture, (possibly) devils and demons—no ecology needed because these guys never eat! Some magical creatures could potentially hibernate for centuries, waiting for something, anything to come by. And of course magic can spontaneously “unfreeze,” or even summon from elsewhere, monsters that have had no need, all this time, to poop. Genies in bottles; anything in a mirror of life-trapping.

In our labyrinth of doom, the gnolls are gravy—the wererats have a magic item and perhaps can fish—the automata and the undead and the demons are anecological—that leaves the small remnant of derro. Can these guys be justified? Can we imagine them eating fungus? Perhaps there is an enormous cavern of fungus they know the twisty underground way to (is it natural? if not, how did it get there? accidentally summoned into existence by a worshipper of Juiblex, lord of slimes and molds?). Perhaps, though, they have become reduced to plundering the ancient tombs of their ancestors, whose bodies were preserved in brine like pickle mummies. The derro must feast upon the flesh of these dead.

Are there enough dead? How about water? Where do they poop? If these questions have no justification, remove the derro. They were there; they just died of starvation and rickets centuries ago.

Or maybe leave the derro alone. Honestly, ¾ of the monsters in any given module don’t really make sense where they are, but get left in for the sake of playability. Who am I to judge?—ah! the compromises our art must suffer!

The delve

Of course, a dungeon alone is just a potentiality. A dungeon is there to get hacked.

Generally a hack starts with a hook. “Fetch me the Soul Gem” (Ghost Tower of Inverness)! Someone needs to expel these horrible creatures from the Caves of Chaos (Keep in the Borderlands)! The Margrave of the March of Bissel has invested in your hack in return for 15% of the treasure (Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth). Of course, one could just tell the party they wake up in a dungeon and have to find a way out (The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan), but that’s a well one can only visit so often. The key with a hook is that it can either be in ignorance of the dungeon’s origin or because of the dungeon’s origin.

In our hypothetical labyrinth of doom, the party could 1. be tasked with a. clearing gnolls from a dwarven ruin, b. recovering some ancient dwarven treasure, or c. locating a particular gnomish automata, all in ignorance of the actual labyrinth (which, if they penetrate it, may pose a pickle—is it a labyrinth best left unhacked?).

Or they could 2. actually seek the evil artifact at the dungeon’s heart because a. they have found a novel way to destroy it, and want to do so before a more competent cult hacks the dungeon, b. they need it for a particular one-shot purpose for the greater good, whereupon they intend to replace it, or c. maybe, hey! evil artifact! Who wouldn’t want that (depends on the payers, eh?)?

The key into the heart of the labyrinth—I mean way past the door that the cult never opened—could be 1. an actual riddle that the party has to solve with superior cleverness to evil cultists, 2. a gimme (item or knowledge) the party recovered somewhere else, and have come to this dungeon to put to use, or (probably best) 3. a similar gimme found elsewhere in the dungeon, perhaps on the corpse of a previous adventurer (who was seeking to pull a 2.) or in the wererats’ hoard plundered therefrom, its meaning unknown until the party comes to the impenetrable entrance to the labyrinth. I say probably best because: While hiding the key to your labyrinth’s penetralia inside your labyrinth is a rookie move that experienced wizards seem often to indulge in, hiding said key far far away, on your person, say, until you die, only to have the key brought to the labyrinth by a doughty adventurer who plundered your grave and sought next to plunder your labyrinth, only to die a wandering monster death on the way…this is choice!

Here is where legibility comes in. Note that even a party who simply blunders upon out hypothetical dungeon (Oo! Dwarven ruins! Let’s fight some gnolls!) will, by the very act of exploration, uncover more and more of the place’s history. If they dare cross the torrent of water, they will find wererats who may be hostile (or may bargain for food), but will certainly have some small information (the legends of our people tell that a century ago, adventurers used to go down that hall and never return). Proceeding deeper, the party will find plenty of reminders of the exploits of the blood cult. And the labyrinth itself could be literally legible, or festooned with admonitory magic mouths (“Whoever you are, you do not want to free the head of Vecna!”). By the time they have reached the heart of the labyrinth, they should have enough information (having gone in, remember, blind) to decide what to do with the artifact therein.

Legibility is hard to ensure in a hack, which is why designers often fall back on clunky apparatus such as journals left behind, or desperate scrawls on walls. I say “clunky,” but such ruses are often absolutely necessary if a party is not going to wander through strange room to strange room in a strange dungeon, merely murmuring, “How strange.” Archeologists find old buildings and spend their lives puzzling over and arguing about the functions of various rooms—I’m not saying that should never happen, but a dungeon is more satisfying if it makes a little more sense alongside the literal wonder (I wonder what this room was for…).

Fortunately, the party can access tools archeologists rarely can, such as speak with dead, commune, divination, stonetell, etc. But also those clunky journals. Even a chatty lich can fill in blanks.

I suppose, from a player’s point of view, learning the history of the part of the dungeon TK can provide valuable hints for the hack. But what are hints compared to the esthetic object of a well-crafted dungeon?

My only regret, now, is that I like my labyrinth of doom dungeon idea and I cannot spring it on my players because at least some of them may read this substack.

What is the first American graphic novel?

I want to find the first American graphic novel—I say American simply because I know very little about comics of other countries; so put down your Tintins and your ACK hardbacks, and let’s see where this leads us.

Hey, even Tolkien fell back on the journal trope in Moria. Although as a novelist he was able to do something that's hard to manage in a D&D adventure and bring characters together with different levels of background knowledge (Gimli, Gandalf, everyone else) and let them interact with the environment to learn more.

Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun is the best published dungeon, Erol Otis was the best D&D artist, and this is well written and thought out.

Most Excellent!