I want to find the first American graphic novel—I say American simply because I know very little about comics of other countries; so put down your Tintins and your ACK hardbacks, and let’s see where this leads us.

Wait: What’s a graphic novel anyway?

Some years ago—I think it was 2008, and was certainly no earlier—I found myself in the audience for panel discussion with graphic novelists. Somehow the rest of the audience was composed of people who had never read a graphic novel. They seemed confused by the idea. A panelist mentioned that there were graphic novel adaptations of Shakespeare plays, and several audience members seemed to latch onto that fact. They asked, somewhat timidly, if it might be possible to create a graphic novel that was an adaptation of…someone else’s plays? The panel had to assure them that not all graphic novels were adaptations!

This seems an absurd story for NYC in 2008, but I was there. It’s a true story. Surely it couldn’t happen today!

Graphic novel is a terrible term. It is never used with any kind of precision. The three graphic novels most non-nerds are likely to have encountered are Maus, Persepolis, and Fun Home, none of which are novels (being memoirs). Somehow Harvey Pekar’s Our Cancer Year and Joe Sacco’s Palestine and John Lewis’s March and Derf’s Kent State are all graphic novels despite their non-fiction credentials. Adrian Tomine’s 32 Stories and Gilbert Hernandez’s Fear of Comics are graphic novels despite being quite explicitly collections of short stories.

Some people claim they reserve the term graphic novel for a book appearing originally as a bound volume as opposed to serialized in a comic. These people are probably having you on; they probably also claim to floss thrice daily. I’ve worked for decades selling comics, and such a distinction is not industry standard. No one primly refuses to label Watchmen or Maus graphic novels because they were originally serialized, any more than we would refuse to label David Copperfield a novel because it was originally serialized. People say “graphic novel” and they just mean a comic with a spine. The word is used interchangeably with trade, which is itself a ridiculous term because it is short for trade paperback and yet is constantly used to refer to hardcovers.1

If a collection of Garfield strips or a Batman Archives volume are graphic novels, that’s one thing. But I’m looking for something a little different. I tend to think crafting definitions is a fool’s game, so we will, perhaps, at best tease out eventually what I mean by graphic novel, but I want at the very least a book in comics form that would be called a novel if it were prose.

Let’s eliminate some suspects

Yeah, I mean, let’s get two out of the way immediately.

The first book to call itself a graphic novel is Will Eisner’s A Contract with God (1978); it’s not a graphic novel, though, at least not in the sense of being a novel. It’s a short story collection. It’s not a genre short story collection, though, and that was unusual at the time. But still not a novel. Also 1978 is going to be a hard sell for first of anything.

[ETA: Oops! First book to call itself a graphic novel was actually Beyond Time and Again by George Metzger (1976); I blundered, but that doesn’t end up changing much of our larger point.]

So let’s look back; all the way back. The first comic printed in America is The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck, which appeared as a newspaper supplement in 1841 and a book in 1849. At eighty pages of continuous picaresque story,2 it’s certainly a novel. But it is immediately disqualified for not being American. It’s an unlicensed ripoff of an unlicensed British ripoff of a Swiss comic by Rodolphe Töpffer! You can’t just make your Eurocomics American through translation and crime!

Several other American graphic novels so-called of the era were reprints of European publications by Töpffer or George Cruickshank. Discard them all! But we still have…

•Journey to the Gold Diggins, by Jeremiah Saddlebags by James A. and Donald F. Read (1849)

Here’s our first contender. It’s indisputably the first original comic in America (that anyone knows about; much lore is lost). It’s a self-contained book. It’s 63 pages of running coherent narrative (about an Easterner who travels to California to search for gold; fortunes and misfortunes; etc.). Shouldn’t this be the first graphic novel?

But here we run into problems we would have addressed earlier under the header Töpffer had we not discarded Töpffer out of hand. Because Jeremiah Saddlebags is very much in the vein of Töpffer. The Read brothers were clearly influenced by and perhaps cribbing off of Töpffer. Both Oldbuck and Saddlebags dance a merry dance that annoys their neighbors; both escape from their respective prisons by growing thin enough to squeeze through a narrow aperture (below).

But lack of originality is hardly the problem. The problem is that we’re looking for a book in comics form that would be called a novel if it were prose and Saddlebags feels less like a comic and more like a protocomic. The transitions between panel and panel (what Scott McCloud would call closure) are often as vast as a picture book. A great deal of the weight of the narrative is borne by the caption below the picture. As the Read brothers lacked some of Töpffer’s genius, there is even less “motion” than in the earlier book. It’s curiously static. Look how much happens between these two panels!

This is someone groping towards comics. So: Is it then comics?

Maybe I’m reaching for an analogy that’s inaccessible but: If I was going to pick the first novel in English I might say Oroonoko and I might say Robinson Crusoe, but I wouldn’t pick Thomas Lodge’s Rosalynde because Rosalynde (pick it up and you’ll see what I mean) is a protonovel. And Saddlebags is a protocomic.

You can find examples of more recent (i.e. real) comics written in this style of staccato, isolated panels: Lynda Barry, Gilbert Hernandez, and Daniel Clowes have all worked this way, and I’m not about to criticize them.

Do you believe me if I say that these panels are different from the panels of Saddlebags? I hope so.

So is Journey to the Gold Diggins, by Jeremiah Saddlebags the first American graphic novel?

PROS

•Literally the first American x, whatever x is, and maybe it’s a graphic novel

CONS

•Perhaps a protographic novel.

You may disagree, but I don’t think this counts, and I’m going to keep looking. Our second contender:

•The Rev. Mr. Sourball’s European Tour: The Recreations of a City Parson by Horace Cope (1867)

I’m jumping ahead a couple decades to a book that is less obviously indebted to (i.e. swipe-filed from) Töpffer. It is, in fact, in some ways the anti-Saddlebags, arch and ironic where Saddlebags is lowbrow slapstick. If Saddlebags is trying to emulate the novels of Tobias Smollett, Sourball is trying to emulate…not Jane Austen maybe, but Maria Edgeworth?

Rev. Sourball goes to Europe for his health, all on his congregation’s dime. He is obliged to fake illness to keep himself in Europe, but eventually his congregation runs out of money and he returns home. That’s the plot. Sorry, spoilers.

I considered this book different enough from Saddlebags to examine on its own, but the objections that haunted Saddlebags are all still here. The pages are captions with illustrations. The illustrations sometimes operate in ironic counterpoint to the captions, which is “sophisticated,”

but we’re still in the realm of the picture book here. With the exception of one particularly energetic sermon (much flailing), this book is even more static than Saddlebags. Also, with one panel per page and many blank (!) pages, the whole thing is only like thirty panels. I have a hard time calling that a novel!

PROS

•We’re still in the nineteenth century, so it sure feels early.

CONS

•Still a protographic novel.

•Too short.

I say nope to this one.

•The Brownies by Palmer Cox (1887)

Oh, come now. This is just a poem with illustrations. Who even nominated this book?

PROS

•Rather charming

CONS

•Oh, come now

•I think Palmer Cox was Canadian

•A Story without Words; or, The New Regime in the United States by William E. Arnold (1894).

Now here’s something different! I’m not quite sure what, because I don’t know much about the (second) Cleveland administration, but this book assures me it was bad. It assures me it was bad through a montage of images depicting America under Cleveland. The images have little to do with each other, but of course by their very juxtaposition, the reader cannot help craft a kind of narrative out of them.

I’m sure knowledge of the times would help the narrative make more, you know, sense. One guy is helpfully labeled “Blount,” so I googled him up and he’s James Henderson Blount. But most people are anonymous.

The donkey in the upper left, helpfully labeled “Dem. party,” stands upon a slowly crumbling platform, helpfully labeled “Dem. platform.” The increasing precariousness of the wobbly donkey gives the sequential narrative an actual (as opposed to merely implied) sequence, although the fact that the donkey never falls is some disappointing anti-Chekov’s-gun meta nonsense if you ask me.

An interesting experiment, but I can’t call it a graphic novel.

PROS

•Tries something different, no?

CONS

•Not sure if it’s comics

•Still too short

•Willie and His Papa and the Rest of the Family by Frederick Opper (1901)

Frederick Opper was definitely a guy who could do comics—creator of the legendary Happy Hooligan, after all—but before he drew Happy Hooligan he drew political cartoons. Yeah, it’s still politics here.

I’m going to reject this one pretty fast, but I want to use it to point out the direction we’re heading. Opper offers us a consistent group of characters: brothers little Willie and rambunctious Teddy, their father, and nurse Hanna. You may have already identified William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt, although somewhat more obscure and also inexplicable is Mark Hanna (McKinley’s campaign manager). The father is, as always, helpfully labeled “trusts.” Their episodic exploits present a narrative of sorts, a narrative propelled by the rise of Teddy Roosevelt and (in general) the ongoing fortunes of the McKinley administration, If you know your history, you will know that this should give the book a rousing climax, but Opper never gets that deep into 1901. Instead he wraps things up with a final page featuring the grim bit of foreshadowing depicted above.

Insofar as Willie has a narrative, though, it is an accidental narrative. It is a diarist’s narrative. These are individual cartoons, and the connection between them is more tenuous than the narrative connections is Saddlebags or the metaphorical connections in A Story without Words.

PROS

•Pretty long

•Characters tell a story, as characters will

CONS

•A series of gag panels is not a graphic novel, no matter what we pretend

But with the inexorable trajectory of a train racing Buffalo to Washington, we are headed down the path that Opper has charted.

•Buster Brown and His Resolutions by R.F. Outcault (1903)

Maybe something comes before this—Poor Lil Mose or something—but take Buster Brown as a symptom. If we can determine that Buster Brown and His Resolutions is among the earliest of graphic novels (spoiler: we’ll do no such thing), we can always go back and look for the very earliest among its precursors. If there were not already in 1903, there would soon be plenty of books very similar to Buster Brown and His Resolutions.

Here’s what Buster Brown gets right. It is, at last comics. From this point on, I won’t be able to say the word “protocomic.” Just look at that closure! Egg McMuffin comics!

But each comics adventure lasts for two pages, and then things start over. It is the Groundhog Day / Cemetery Man / treadmill hell of the comics strip. It’s no more a graphic novel than your favorite Dilbert collection.

I should also add that, because (as with many of the books discussed up to now) Buster Brown is only printed on one side of the page, there are only thirty-some odd pages of content in the book.

PROS

•Egg McMuffin comics!

CONS

•Not in the least a novel (i.e. not a sustained narrative)

•Also not a novel b/c it’s too short

If we can finagle our way around those cons, we might find ourselves lucking into a graphic novel

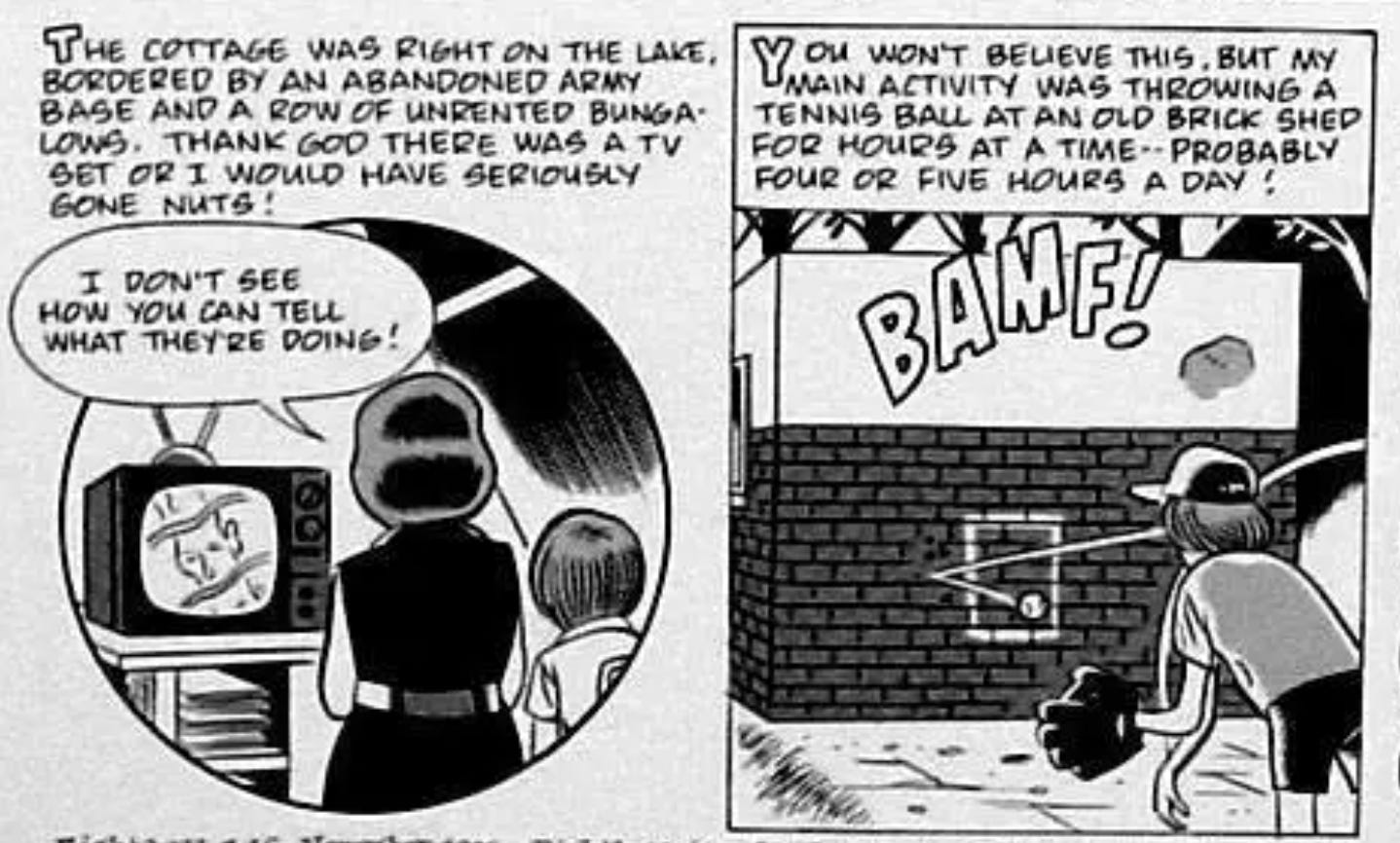

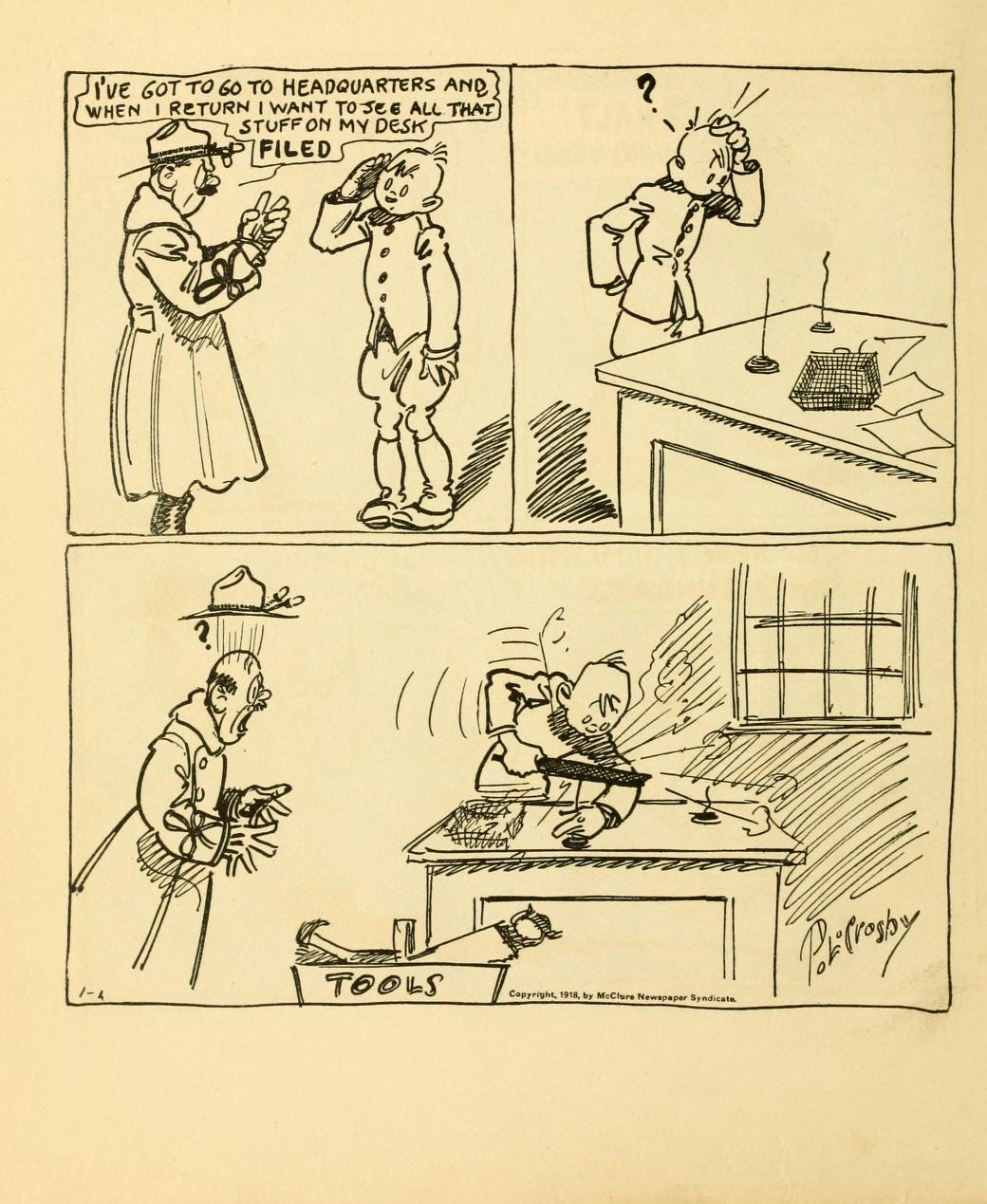

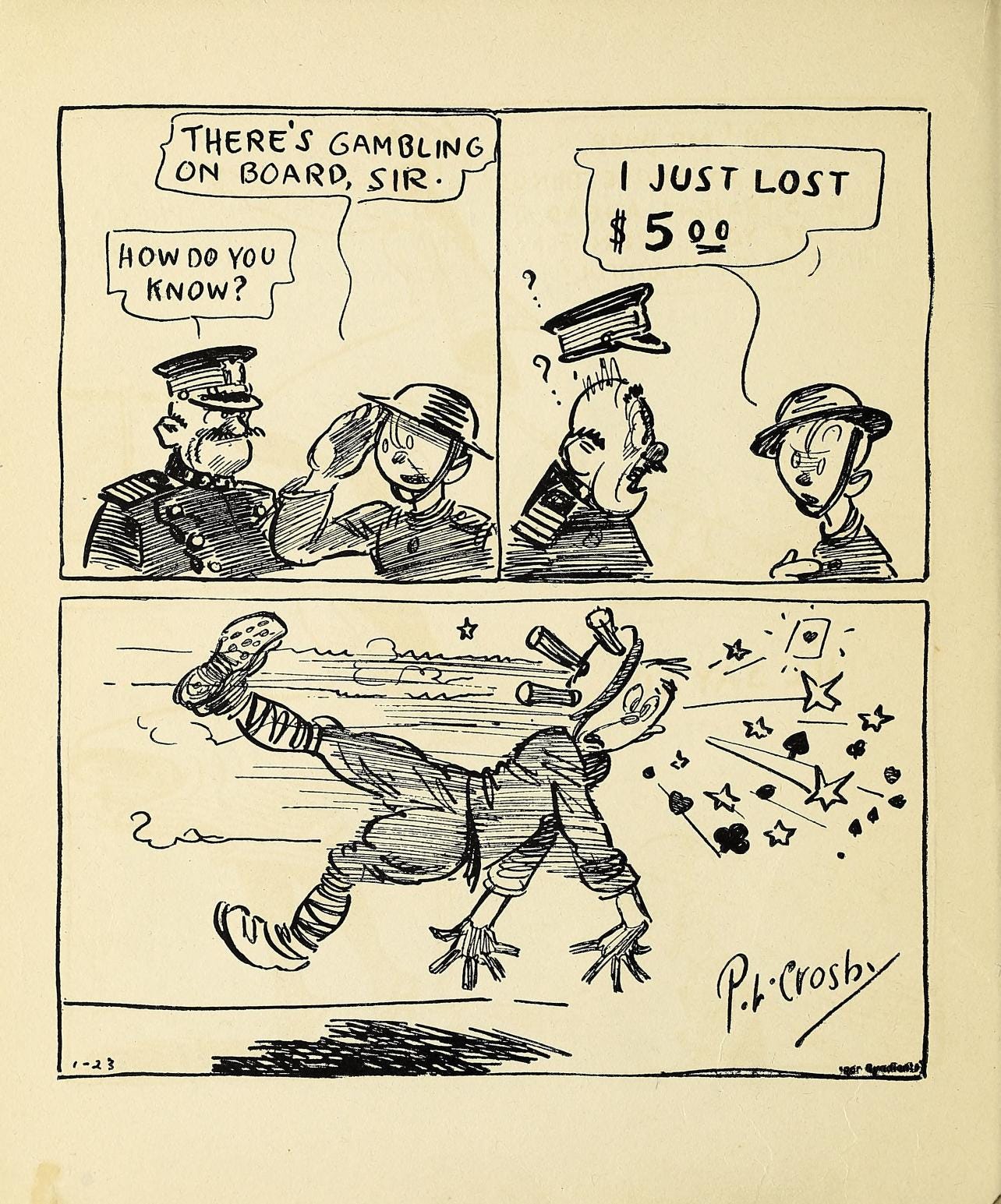

•Between Shots by Percy Crosby (1919)

Like Opper and Outcault, Percy Crosby has cartooning credits, having gained immortality of sorts with his kid strip Skippy. If you don’t know Skippy, you certainly know its offspring: Peanuts is an homage to/reaction against Skippy, and Calvin and Hobbes is just Skippy + Barnaby.

But that’s all in the future! In the future Percy Crosby would create America’s most popular strip and then drink himself into the madhouse while Skippy peanut butter runs off with his intellectual property (strange but probably true). Our mission is to see if back in 1918 Crosby could also create the first American graphic novel.

Probably not, right?

Crosby was a professional cartoonist when WWI started, and he continued to cartoon from the literal trenches, his work sent back to the states for syndication. The first collection of these cartoons, That Rookie from the 13th Squad (1918), was full of solid gags like this:

Hardly a graphic novel any more than Buster Brown (or Dilbert). But then came his follow up, Between Shots, which is on one hand more of the same,

but on the other hand has a narrative arc: The book starts with our rookie sailing to France; he serves under fire; he lingers in France after the Armistice; he sails for home and kisses the first American sidewalk and the hem of the first American girl he meets.

This is not only a narrative, it is a narrative with more gravitas than any comic hitherto examined (it’s the Great War, bro!)! But, much like in Willie and His Papa above, it is the accidental narrative of history. Crosby was a solider, and drew disembarking comics when he disembarked; frontline comics when he was at he frontline; postwar Paris comics after the war; nostotic comics as he performs his nostos. Almost any American soldier (casualties excepted) is going to have the same story in the same order. C’est la guerre!

PROS

•A protracted narrative on a serious subject

•Actually printed on both sides of the page, so it’s just as long as it looks ( >100pp.)

CONS

•The narrative is an accidental afterthought

I am still rejecting this. But what would happen if we could find a comic with a narrative that someone had actually planned out; you know, like a story?

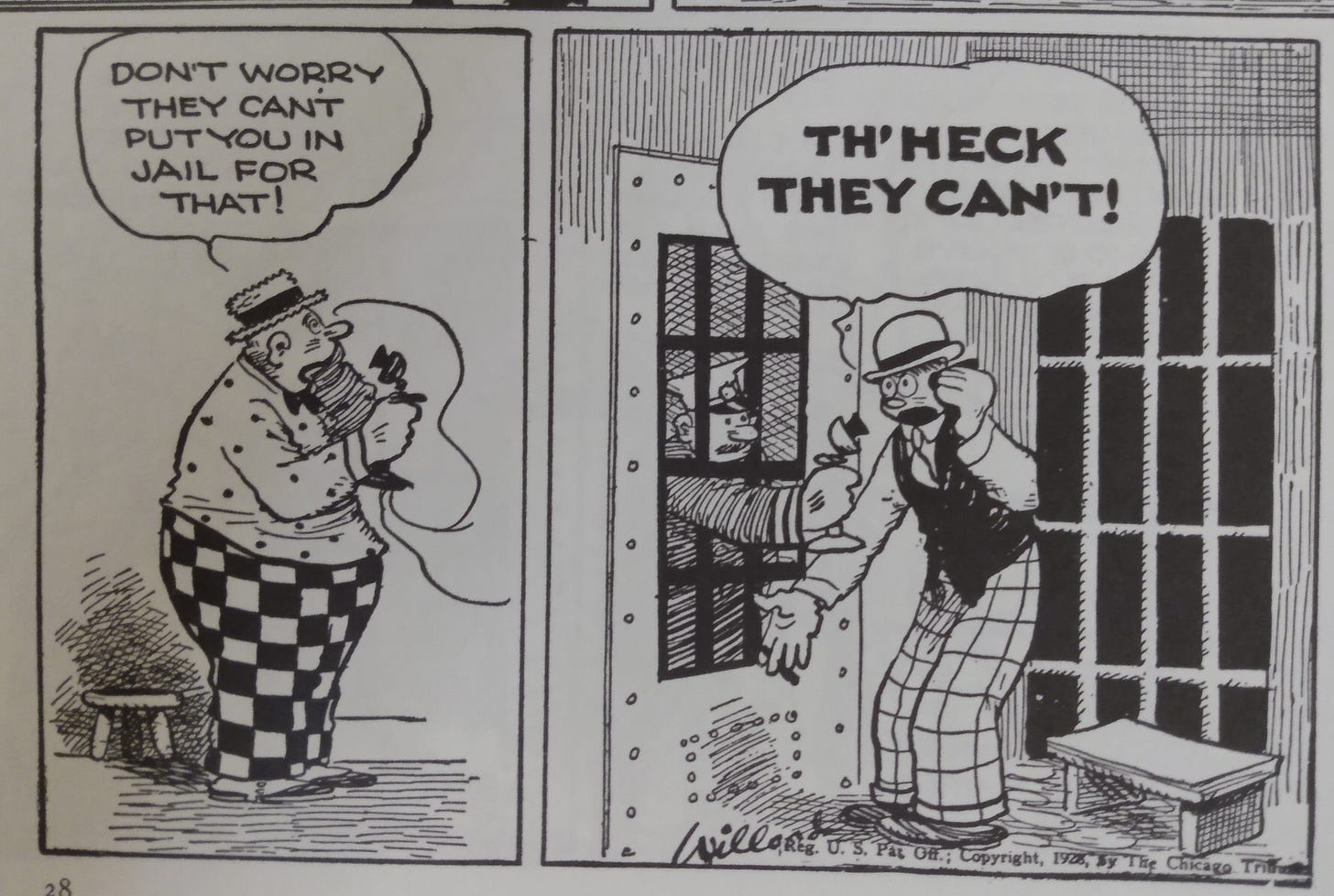

•Moon Mullins by Frank Willard (1927)

(I’ve never actually read the 1927 Moon Mullins, but I read a 1929 volume known as Moon Mullins Series 3, and I’d wager it’s the same basic thing. Assume everything I say about Moon Mullins Series 3 refers to Moon Mullins [Series 1].)

And here we’re on to something! Here we have a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end. In payment of a gambling debt, Moon Mullins receives what he does not know to be a stolen car. Trouble with the cars’s real owners, trouble with the law, and then, at last, the true culprit is unmasked. Happy ending. The book starts elegantly, introducing first the car’s owners, establishing a conflict with our protagonists, later alluding to the fact that their car is stolen, and only then interweaving in the gambling debt. It ends in a somewhat odd fashion—the whole plot is wrapped up nicely, and then there are three pages of somewhat extraneous and random material. That’s only three pages, but as the whole book is only 46 pages long, it’s not an insignificant percentage.

Fred Willard is a great cartoonist—perhaps not as great as Percy Crosby was in 1927, but certainly better than Percy Crosby was in 1919, when the last book we examined came out. This is a solid story with solid cartooning. And yet…

Moon Mullins was a daily comic strip. This volume in question is a collection of daily strips, one strip per page. Strips were bigger back then, and you can fit more action into Moon Mullins’s four panels than you can in the one or two panels of a contemporary daily strip like Mark Trail or Mary Worth—46 days of Moon Mullins has enough story to feel like a graphic novel, something that sounds counterintuitive to the newspaper reader of today.

I know I said way back at the beginning that being originally serialized was no impediment to being a graphic novel; I cited Watchmen and Maus; I’m not crazy. But although Moon Mullins is serialized and has a perfectly good narrative, it seems perverse to me to call 46 strips yanked from an ongoing run the first graphic novel. Fred Willard didn’t plan for it to be a novel, especially not a 46-page one like this book! We know that’s true because the story is only 43 comics long—three extraneous days at the end. He was just spinning yarns, one after another.

Moon Mullins ran for almost 25,000 strips over the course of eight decades. Not all of it was a serial narrative, the way it was in the ’20s, but a lot of it was. Can we really pretend that Moon Mullins is just a sequence of hundreds of novels? I have a hard time pretending that.

I picked Moon Mullins because it’s old and I like it. It’s the first collection of this kind I could think of. But many other strips of the era also found themselves easily falling into discrete stories, many were also collected into books, and for all I know some of them may predate 1927—

(Oh! Poking around, I just found that Little Orphan Annie had it’s first collection in 1926! Later Annie collections were “novelistic” (such as 1933’s LOA in Cosmic City), and maybe the 1926 collection is, too)

—but here’s the thing. Even if Barney Google or Gasoline Alley didn’t have 1920s collections that encompassed single stories, they still had those single stories. Follow me here. In 1937–38, the Mickey Mouse comic strip had a long story sequence known as “The Monarch of Medioka.” To the best of my knowledge, it was not published as a standalone volume until 1988. But if it was a novel in 1988, wasn’t it a novel in 1938? If all the chapters of a book are published serially ala David Copperfield, but the chapters are never collected between two covers…isn’t David Copperfield still a novel? This is not necessarily a hypothetical question. Horatio Alger’s Cast upon the Breakers was serialized in the nineteenth century but not collected until the 1970s. Isn’t it a nineteenth-century novel?

What I’m saying is that if we can take 46 Moon Mullins strips out of 25K and call it a graphic novel, can’t we take 46 strips any number of times out of the infinite sea of comic strips and generate hundreds or thousands of retroactive graphic novels? Which one of those is first? Am I talking crazy here?

PROS

•A lengthy narrative in sequential-art form

•More satisfying as a narrative than any of the above, honestly

CONS

•Just a small moment, drawn ex post facto from an ongoing story

•Potentially opens the floodgates for an infinite number of ex post facto graphic novels, and then where would our quest be?

Let me just say that from here on in, I mean for this book and all following, if you disagree with me and want to take any of these picks as the first graphic novel…I can’t really fight you. I don’t think they’re the best answer, but they’re not bad answers. Maybe on another day I’d agree with you. I’ll come to my pick, and it’s not yet, but pax to all who diverge from my judgment.

Nevertheless, despite their merits, I cannot bring myself to accept Moon Mullins, or Little Orphan Annie, or hypothetical Gasoline Alley in the Adventure of the Sudden Skeezix. This road (which we have followed through Opper, Outcault, and Crosby) is a dead end. But there are other, surprising roads, arising from unexpected directions.

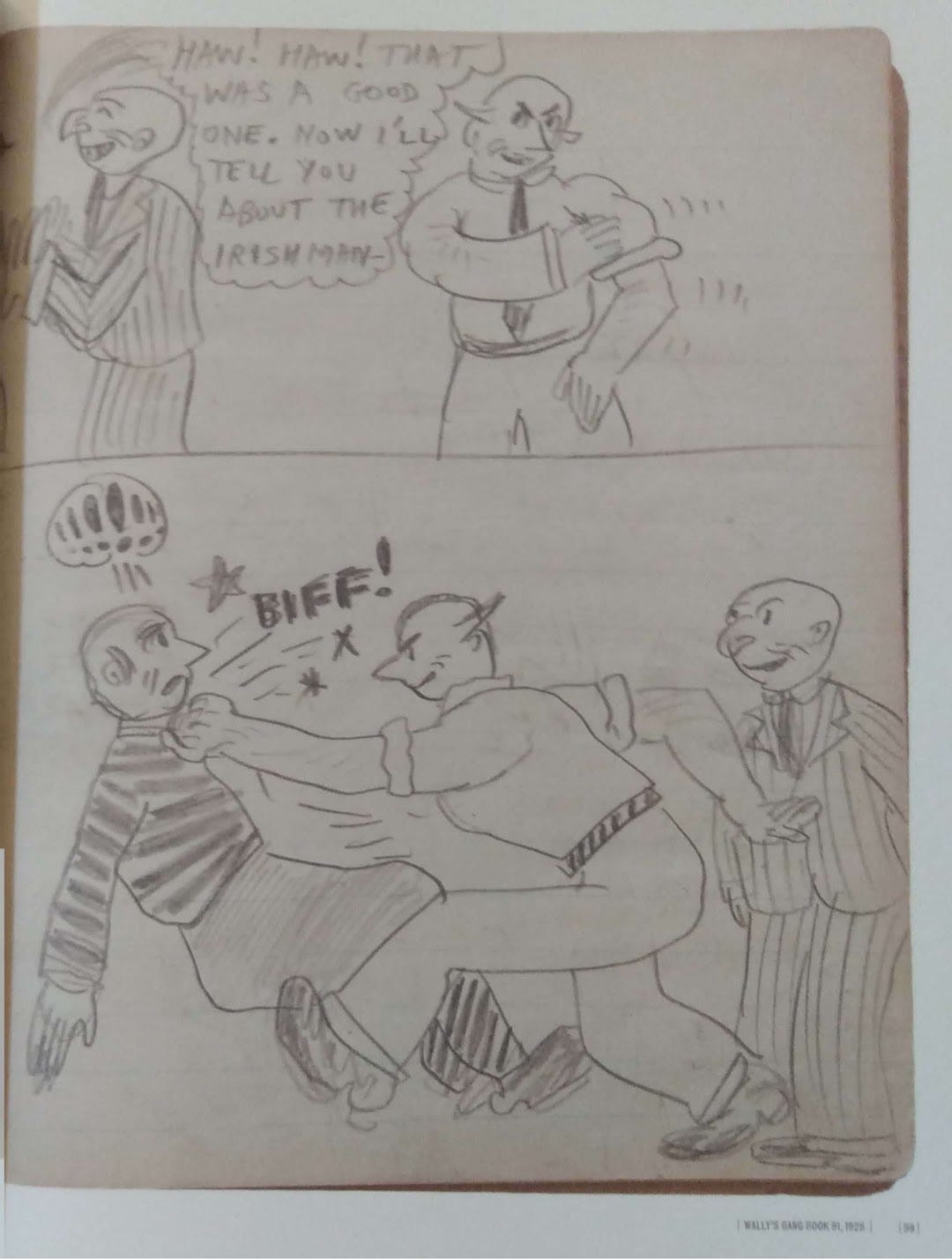

•Wally’s Gang #91 by Frank Johnson (1928)

No one saw this coming, but at some point in the 1920s, a kid in Chicago started filling notebooks with comics about a bald narcissist and his gang of sweater-wearing pals. This is before comic books existed—only strip collections like the Mullins above—but young Frank Johnson did not make strips. He made…um…graphic novels?

Frank Johnson apparently never showed anyone his comics. He died in 1979, and somehow much of his life’s work eventually made it into the hands of comics historians, who have curated it into art shows and selected some for publication. What happened to the first ninety (!!) notebooks of Wally’s Gang is anyone’s guess, but the ninety-first, completed in 1928 when Johnson was sixteen, is, yeah, kind of a graphic novel. A composition notebook, its blue guidelines used to help freehand panel borders, holds a penciled adventure in which Wally seeks to win a bike race despite the machinations of various frenemies.

Both art and story are crude, but crudity is no barrier; we’re just looking for priority (and Johnson would get much better as he aged, of course). He completed 37 more increasingly competent volumes of Wally’s Gang, plus various side projects, before he died, but its only the first volume that concerns us—or rather the ninety-first, since at least it survives. Is it a graphic novel?

On the one hand, clearly yes. It’s a long narrative, it’s a comic, and it’s bound together as a book. It’s only one in a series of volumes about Wally and his gang, but that is no more an obstacle than it is for Tarzan or Nancy Drew novels.

But it’s also not published. It’s not even inked! Am I going to say that the first graphic novel in America was secretly scrawled out by a sixteen-year-old obsessive and hidden in a trunk for decades?

Comics, as we will return to later, is among other things a tradition. Young Frank Johnson is self-consciously aping that tradition, but he’s not part of it. He’s not inside it. You can’t make outsider art3 unless you’re outside it! No one ever saw his work, at least until after he died (in 1979). If you invent a polio vaccine and then never tell anyone, I don’t think you get to “scoop” Salk. I’m nixing this.

(Also it’s only like 30-odd pages long; I know some later volumes are 100+ pages, but I don’t know what year we reach that length.)

PROS

•More or less just a regular graphic novel

CONS

•Too short

•Never published

•Outsider art

•Dead branch

•God’s Man by Lynd Ward (1929)

From almost the exact opposite direction and one year later we get out next contender: a “novel in woodcuts” (per the cover) told entirely without words by Lynd “Biggest Bear” Ward.

Unlike a teen mad genius amusing himself in a (presumably) basement, Lynd Ward was a fine artist addressing big themes in art and politics. His book is an adult book, by both definitions of the term—I mean it’s about modern alienation and it shows boobs.

So: It’s self-consciously a novel. It’s sequential art. Do we have a winner?

Here’s my objection: God’s Man looks like a graphic novel to us, but this is because we live in a post-Scott McCloud world. I said I wanted the first graphic novel to be in comics form, and Outcault, Crosby, Willard, and even Johnson were self-consciously making comics. They were trying to work in the comics tradition (Outcault practically invented it). But Ward is operating in a different tradition, self-consciously aiming to be like Belgian artist Frans Masereel who made earlier “wordless novels” (not considered here due to insufficient Americanness). And I do mean self-consciously—the woodcut medium, the page-sized panels, the progressive politics: Ward is Masereel’s disciple.

And Ward did not think he was making comics any more than Masereel thought he was making comics. No one else thought they were making comics either—Thomas Mann called one of Masereel’s books his favorite movie (!). In his retrospective essay on “pictorial narrative,” Ward name-checks comic books and comic strips (as well as Egyptian murals) but makes it clear that his inspirations are all fine artists.

God’s Man (and Ward’s subsequent, similar, silent books) is well worth reading for fans of the graphic novel, but it can hardly be the first graphic novel if it is trying so hard not to be the very thing that graphic novels must be viz. comics.

PROS

•In some sense it’s a graphic novel

CONS

•It’s only comics thanks to Scott McCloud!

•Go back to Europe!

•She Done Him Wrong by Milt Gross (1930)

Milt Gross is a great cartoonist!—only Percy Crosby, of all the people we’ll consider, is better—and in 1930 he wrote what he called “the great American novel.” So is it the first American graphic novel? This is honestly the closest we’ve come so far, but I’m still going to say no.

She Done Him Wrong is in content a parody of Hollywood melodramas but in form a parody of Lynd Ward’s God’s Man (and similar works). The art is as close as Gross’s pen can come to emulating a woodcut. (If you didn’t know what he was aiming at, you might wonder why the pictures looked that way). Gross is, in other words, still woking in the Masereel tradition—and note again the tie-in to movies. Sure, Gross is himself a cartoonist, a veteran of comic strips and (later) comic books, but that fact doesn’t make She Done Him Wrong comics any more than it make Gross’s various prose works (Nize Baby, Dear Dollink, etc.) comics.

This is going to be my objection to the other wordless American novels an energetic young contrarian might want to trot out to stymie me—William Gropper’s Alay-oop (1930), Fiacomo Patri’s White Collar (1975), or Myron Waldman’s Eve (1943), say. These books represent a parallel tradition, similar to comics, someday to be absorbed by the rubric comics, but operating on its own set of assumptions and ultimately to a greater (Patri) or lesser (Waldman) extent looking back to or through Ward.

PROS

•Closest thing yet

CONS

•We’re still in Masereelland

•We never left

(While I have this Milt Gross in my hand, I’ll also summarily dismiss his 1939 That’s My Pop Goes Nuts for Fair, a souvenir book from the 1939–40 NY World’s Fair, as being more a series of vaguely connected gags than an actual narrative. I calls ’em etc.)

•Four Immigrants by Yoshitaka Henry Kiyama (1931)

Okay, now we’re out of Masereelland, and things are interesting again. Because in 1931 a Japanese expatriate in California published a semi-autobiographical account of the adventures of four Japanese immigrants in San Francisco—as a hardcover book made up of fifty-two two-page comics episodes (so that’s 104 pages in the book).

Yoshitaka Kiyama had initially intended the comics in his book for syndication in Japanese-language Californian newspapers—there were fifty-two installments so it could run weekly for a year—but that never materialized. In 1927 Kiyama displayed the comics at an art show (he was also a fine artist), but he didn’t publish them until ’31.

Our four heroes—with big dreams and the new American-friendly names Henry, Fred, Frank, and Charlie—enter San Francisco by page two, try hard to get along in the new country, and on the final page two of the four head back to Japan. So we have a plot, and at 104 pages, that plot makes a novel.

One could carp that this is (like so many so-called graphic novels) not a novel but a memoir. I obviously have no idea how much is made up here, but I dismiss said carping by the purely subjective handwaving that (unlike, say, Fun Home) Four Immigrants reads like fiction. Frederick L. Schodt in his introduction to the 1999 reprint says that “while Kiyama took certain liberties and created some composites of experiences, the story in the manga…was far more of a documentary that [he] had originally suspected,” a statement that backhandedly supports my subjective impression. If you have to interview an author’s daughter to learn that he’s not writing fiction, then, brother, that means the text presents as fiction.

So don’t worry about that. But I’m going to carp nevertheless. This book is neither outsider art (like Frank Johnson’s) nor an attempt at aping European art models (like Lynd Ward’s), but it’s also scarcely inside the American comics tradition. It’s published in America, but it’s got one foot in Japan. I don’t want to be jingoistic here, I just mean that if I’m going to exclude the whole stream of wordless graphic novels as being a parallel tradition, surely I should exclude this one as well.

My talk of traditions is complicated by the fact that Kiyama (like Johnson but unlike Ward) is clearly inspired by the American comic strip, right down to the (idiosyncratic for a Japanese) panel placement. But although Kiyama published his novel in two different ways (publicly at an art show and (better, for our purposes) as a hardcover), it does not seem to be widely distributed, even among the limited potential American audience (of Japanese readers). It must have had more readers than Johnson’s comics, but but, honestly, how many more?

So I’m saying no.

PROS

•Technically published

CONS

•We are still technically in the land of newspaper strips, even if this one didn’t get off the ground4

•Super obscure

•Insufficiently American

I’m going to skip right over The Bowser Boys (1948) because we already did Frank Johnson, and he hasn’t cleaned up any of the “cons” problems with Wally’s Gang except the length (The Bowser Boys is 80 solid pages, much of it actually inked (!)); BB is also as episodic as any strip collection, even if these boozy lowlifes could never have passed a syndicate’s censors. Skipped! To get to the good stuff, viz.:

•It Rhymes with Lust by Drake Waller, Matt Baker, and Ray Orsin (1950)

And here it is, trumpets sound etc. In 1950 publisher Archer St. John sought to cash in on the rise of mass-market paperback books by creating a “picture novel”—projected first in a series, even if the series never materialized. Comics veteran Arnold “Doom Patrol” Drake, one half of the Drake Waller pseudonym (Leslie Waller was the other) came up with the term “picture novel” as well as the picture novel logo. The book was (he told The Comics Journal in 2006, the year before his death) his brain child, a longer, more adult comic to appeal to “ex-G.I.s who read comics while in the service.”

For the art they got Matt Baker, by far the best draftsman of any cartoonist we’ve encountered, and one of the highlights of the Golden Age of comics. Baker is perhaps best remembered today for drawing that Phantom Lady cover (#17, 1949) that gave Fredric Wertham such conniptions in Seduction of the Innocent, but he’s more than just a cheesecake artist. It’s not really important for our purposes that his work on It Rhymes with Lust be great—although it is great—but it is important that it be comics, and it’s certainly that—the wordy, dialog-heavy kind of comics that would remain in favor up through the 1980s.

(I have no idea who Ray Orson is; I guess he inked this piece.)

Outside of the art, It Rhymes with Lust isn’t very good, just a trashy melodrama——but this is comics, so that makes it better! We’re looking for a novel in comics form, and in 1950 the comics form meant sometimes funny animals but often straight-up trash. Lust delivers! What could I possibly say against it? No surprises here; I will not be the first to hail It Rhymes with Lust as the first American graphic novel, although I hope the rigorous scientific method I have used to come upon this answer was of some value.

PROS:

•A graphic novel in every sense of the word

CONS:

•None…

…oh, except that this book ↴ came out the same year and no one knows which one was released first.

I’m arbitrarily choosing the one I’ve read. Begone, Mansion of Evil! ❦

Appendix: Where can I read these things?

Many of these books are public domain, and available free for all; many others have been reprinted, and are inexpensive. I’ve tried to collect places the curious can find the texts to check my work/nitpick my errors:

•The Adventures of Obadaiah Oldbuck: public domain

•Journey to the Gold Diggins: public domain

•Rev. Mr. Sourball’s European Tour: public domain

•The Brownies: public domain

•A Story without Words: public domain

•Willie and His Papa and the Rest of the Family: public domain

•Buster Brown: public domain, but I don’t know where to find the 1903 collection; a 1904 collection is here

•That Rookie from the 13th Squad: public domain

•Between Shots: public domain

•Moon Mullins: Series 1 in public domain, but I don’t know where to find it. Series 3 was reprinted (alongside Series 5) by Dover Press in 1976 as Moon Mullins: Two Adventures

•Wally’s Gang & The Bowser Boys: Earlier this year Fantagraphics started reprinting these works with Frank Johnson, Secret Pioneer of American Comics Vol. 1

•God’s Man: This has been reprinted several times, including by Dover Publications and in the Library of America Lynd Ward: Six Novels in Woodcuts volume 1

•She Done Him Wrong: reprinted by Fantagraphics in 2006

•That’s My Pop Goes Nuts for Fair: reprinted as Milt Gross’ New York by IDW in 2015

•not all the wordless books mentioned have been reprinted to my knowledge, but Firefly Books’ Graphic Witness collection contains some (the second edition has five wordless novels to the first edition’s four)

•Passionate Journey was also reprinted standalone by Dover

•Four Immigrants: translated by Frederick L. Schodt as The Four Immigrants Manga and published in 1999 by Stone Bridge Press

•It Rhymes with Lust: reprinted in 2007 by Dark Horse and in 2006 as a special bonus feature in The Comics Journal #277

•Mansion of Evil: no idea; it never happened!

Notes towards an Understanding of Daniel Clowes’s Monica

(As always, I encourage you, if you like my writing but wish an editor would “tone it down,” to indulge in some of my books, in which a sober editor has done just that.)

Just because I happened to come across it today, a revealing quotation that reveals the absurdity: “Kevin Feige…would bring stacks and stacks of hardcover trades etc.” (Robinson, Gonzales, & Edwards, MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios (Liveright, 2023) p. 117.)

Also reformatted as forty pages, mostly by what might technically be called “stacking.”

As Johnson obviously does.

Of course, technically Action Comics #1’s Superman story is also in the realm of (failed / grounded / inchoate) comic strips; lots of things were supposed to be comic strips back then!

Mansion of Evil can be read here: https://digitalcomicmuseum.com/index.php?dlid=33408

The original version of It Rhymes with Lust can be read here: https://digitalcomicmuseum.com/index.php?dlid=27911