Movie Explainer: What is Stand by Me about?

Surprise! It's about Saturn eating his children!

(This substack is about books and maybe history, but I thought I’d extend the self-indulgence of my birthday week to writing two or three explainers about movies, and WHAT ARE THEY ALL ABOUT? This is the first.)

Everyone knows what Stand by Me is about. It’s a bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story. Young Gordie LaChance undergoes a harrowing and even Campbellian journey into the wilderness towards death, and comes out of it on if not a man then at least well on his road to manhood. Without this journey (which is, of course, nearly the entire runtime of the movie), his life would have been different; weaker; incomplete. He would never have become (because the movie is also a künstlerroman) the writer he grows up to be. Gordie becomes fully human over the day and a half of the events of Stand by Me.

Sure, that’s what most of Stand by Me is about. But this is a movie with a twist ending. This is Sixth Sense. This is Witness for the Prosecution. This is a twist so clever I didn’t realize it the first half-dozen times I watched the film.1

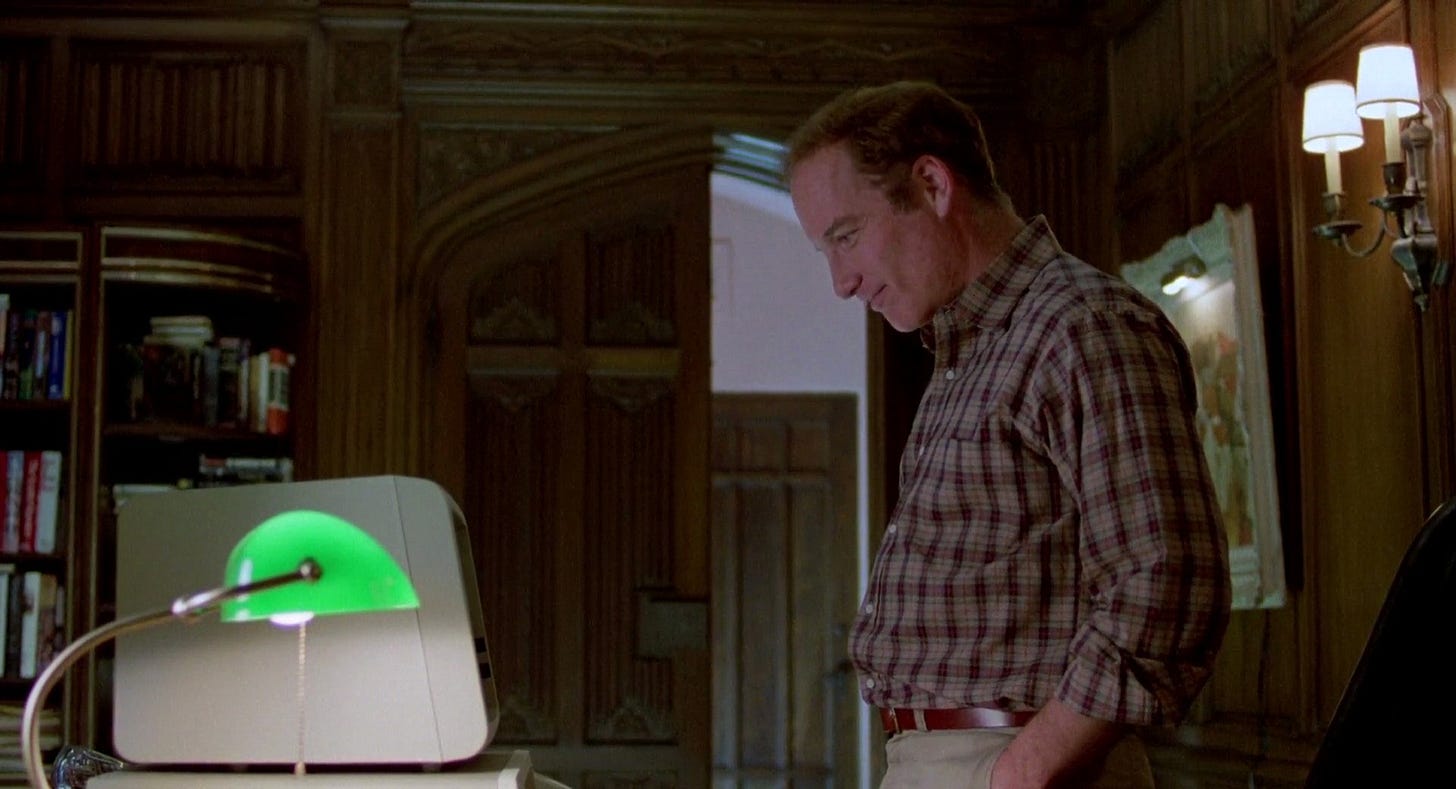

The movie, you will recall, takes place in 1959, when Gordie is twelve. But it has a frame narrative in which an adult Gordie (presumably in his late thirties) reminisces about the events of the summer of ’59. By the end we learn that he is typing up his memories on a very 1986 personal computer, crafting one of those stories he has excelled at since his youth. Here in the mid ’eighties, Gordie (Gordon?) lives a successful bourgeois life in a neatly-manicured home in the suburbs. He is a (professional, apparently) writer. His study has built-in bookshelves and double (!) doors. He has fathered a twelve-year-old (approx.) son. He has, the movie wants us to perceive, “made it.”

And outside, as Gordon finishes up that story of his, lurks that twelve-year-old son. Young Gordie Jr. and his friend, they want to go to the swimming pool. They reeeeally want to go to that swimming pool. For the last hour they’ve been loitering, waiting for dad to drive them. The last shot of the film is everyone piling into the car and motoring away for summer fun.

Now, the parallel between Gordie Sr. and his friends on one hand and Gordie Jr. and his friend on the other hand are right there in the text. Adult Gordon looks dead at the two young ’eighties chums and types: “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?” It’s pretty overt.

And like Gordie Jr., 1959 Gordie wanted to go somewhere. His parents weren’t going to take him. So did he spend an hour wingeing about it until finally a harried father drove him down the Back Harlow Road? No, he did not. He packed up camping equipment and a gun, purchased provisions, and set out on a perilous overland voyage, quite literally risking life and limb. He got to swim, too, but in a leech-infested swamp.

Now, at last, Gordie Jr. wants to swim in a pleasant, safe, chlorinated suburban pool. When the lifeguard cals “adult swim,” he will whine a little, but soon he’ll bully his father into forking over a buck or two for pretzels at the concession stand. Soon it’ll be all-swim again, and he’ll go back to playing Marco Polo until his watchful father says it’s starting to get late. “Aw, shucks,” he’ll say, but it’s a short drive home.

All of that sounds better than leeches! Who would want to suffer through a trip like young Gordie’s? But remember: The first eighty minutes of the movie assert that this trip is how Gordie became a man! His very humanity is vested in a train-dodging, gun-toting, corpse-filled journey. And he has spent his adult life systematically stripping his son of any chance of becoming fully human in turn.

How do you get to the pool? Do you walk? It can’t be a two-day journey! Do you hitchhike? What if you got on a bike? There’s no way that pool is more than a hour away by bike—and you’ve already spent an hour whining about the fact that you’re not being driven there!

But Gordon Sr. never says, “Find your own way to the pool.” He never says, “If the pool is too far away, find a pond nearer by.” He never says, “Go make your own fun with your own friends; you shouldn’t need me.” He doesn’t even say, “Maybe if you wander around, you’ll get to see some deer.” Instead he says “I’ll be right there.”

“That’s what he said a half hour ago!” But his cowed child, perpetually trapped in infancy, crouches sulkily and waits. And what’s his father doing this whole time? “Abide awhile longer in your ape-like state while I contemplate my own humanity!” While I contemplate my own humanity! He’s thinking about the very moment he became more than his child!

Gordie Jr. never has a chance. Haunted with Oedipal fears, Gordon laC., like Saturn before him, has consumed his son.

My book Impossible Histories has a whole chapter about Boomers and Oedipus, but perhaps Stand by Me lays out more effectively everything I had to say.

And that’s what Stand by Me is about.

Great film, though.

“Abide awhile longer in your ape-like state while I contemplate my own humanity!”

The past is a foreign country I: Revenge of the Nerds

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from the past few years it is that human beings have no long-term memory. We are unable to conceive of what the world was like even in the recent past. In 2006, when Chip Taylor wanted to characterize the two political parties, it was the Democrats he decided to call “conspiracy flingers” (hear it

Props to my wife for first pointing it out to me.

I thought I had an adventurous and occasionally risky childhood. But then I heard stories from my uncle and it doesn't even compare! They went freighthopping on trains, rode across state lines, and caught another train on the way back. I can't imagine my child doing anything close to that, I'd die from worry. And it is a shame. Is this a global phenomenon or just a Western one? I wonder if anything like this has happened in history--that would be an academic gold mine.

Nice take!