(Once again I lost the ACX book-review contest. Previous prize-losing (though admittedly less spectacularly prize-losing) book reviews can be found as follows: Watership Down; Albion. The current loser is below. If you like any of these reviews, please note that I write books you may also enjoy.)

“What can I but enumerate old themes…”

•Yeats, “The Circus Animals’ Desertion” (1939).

Some artists return again and again to their favorite well, same old bucket in hand. Alfred Hitchcock never tires of reminding people that they are one false accusation away from being a fugitive from justice; Jane Austen has a hard time keeping readers in suspense about whether or not her heroes will get together in the end (they will); J.W. Waterhouse will paint the same beautiful woman over and over and she will never have ears; Lord Byron didn’t get the Byronic hero named after him by, you know, mixing it up.

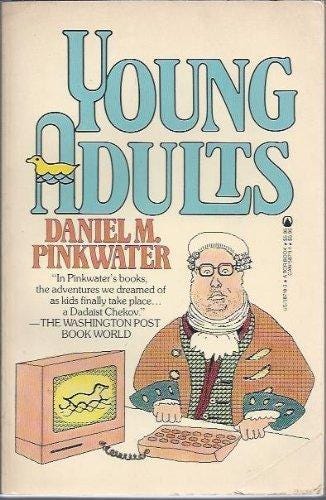

But few artists have hammered on the same theme as resolutely as Daniel Manus Pinkwater; and no artists I can think of have ever looked back at their particular obsession and commented on it so thoroughly, even savagely, as Pinkwater did in his 1985 volume Young Adults. In this review, I’ll (I.) consider the book in question, (II.) briefly touch upon Pinkwater’s favorite themes, and (III.) try to tease out how one book of dirty jokes—I mean the book being reviewed—reexamines and critiques these themes.

Part I: The Structure of the Work

All of Young Adults is divided into three parts: two novellas and one chapter of “a novel to be completed sometime or other.”1 (The first novella was published three years earlier as a separate, apparently stand-alone work. The rest of the material appears for the first time in Young Adults.) Let’s take these parts one at a time.

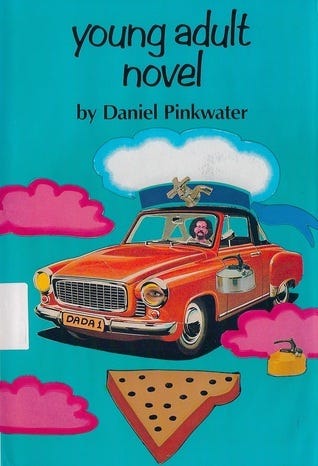

a. The first novella, entitled Young Adult Novel

In this section we meet the Wild Dada Ducks, five high school students who are devoted to the early twentieth-century art movement Dada. They all have Dada names such as the Indiana Zephyr or Captain Colossal—Charles the Cat is our narrator—and these names are all anyone ever uses (with a lone exception: At one point a counselor lets slip that Igor’s “slave name” is Maurice). They dress, as befits serious artists, in a dignified fashion, meaning neckties and also perhaps baby carriage wheels and a banana on a string etc. The Ducks are aware that “Dada is generally a misunderstood art movement”; as might be imagined, despite their attempts to bring culture to Himmler (!) High, the Dada Ducks are not very popular.

Young Adult Novel is quite explicitly a parody of young adult literature as it existed in the mid-eighties—or at least part of it is. The Ducks are engaged in an ongoing collaborative art project, a Dada young adult novel titled Kevin Shapiro, Boy Orphan. Several chapters of this art project are interpolated into the narrative of Young Adult Novel. As any YA protagonist of the time might, young Kevin Shapiro suffers through abuse, addiction, pregnancy (a surprise, that one), and then “instead of winding up with a lecture from some kindly adult about moral responsibility and another chance for Kevin, we [the Ducks] would just kill him off from time to time. [Later] we would just bring Kevin back for another chapter of tragedy and degradation, and kill him again when it got boring.”

The slim plot kicks off when the Ducks learn that a kid named Kevin Shapiro actually attends their school. This, the real-life Kevin Shapiro, is a shrimpy comic book nerd, and the Ducks decide to make him a local celebrity through their art. By miracle, they succeed, but an embittered Kevin Shapiro, who just wants to be left alone, uses his newfound popularity to lead the rest of the school in a lunchtime assault on the Ducks, in the course of which our heroes are coated with mushy Grape-Nuts.

Unable to fathom what went wrong, the soggy Ducks seek a moral from their experience.

“It has no moral,” their leader (known as the Honorable Venustiano Carranza (President of Mexico)) tells them. “It is a Dada story.” With these words, Young Adult Novel ends.

b. The second novella, titled Dead End Dada

Disheartened—explicitly by the looming threat of nuclear annihilation and implicitly by their humiliation at the hands of Kevin Shapiro’s followers—the Dada Ducks decide to give up on Dada and embrace Zen Buddhism instead.

Unfortunately, the newly rebranded Dharma Ducks know almost nothing about Zen, and have to cobble together an understanding from memories of kung fu flicks, one specific issue of a Dr. Wizardo comic, and (especially) a brown-rice-themed health food cookbook.2 Aware that their comprehension is inadequate, the Ducks seek out a Zen master, homing in on the only Asian person they can find: Sigmund Yee, owner of the local laundromat. Yee wants no part of this; he calls the Ducks “little racist bastards,” accuses them of being addled by drugs, and chases them away, but our heroes decide that Yee is behaving exactly as a real Zen master would and search for coded wisdom in his statements.

The Dharma Ducks will need all their Zen fortitude because a series of amusing mishaps soon gets them publicly labeled as chronic masturbators, whereupon they are forced to attend three periods of remedial gym every school day (ostensibly so they’ll have no energy left over for self-abuse). A litany of sufferings then rains upon our heroes: health problems; dead pets; academic failure; compulsory attendance at the Anti-Communist White American League Rifle and Machine Gun Class and Sunday School; “Captain Colossal’s parents announced they were getting a divorce. They told the Captain it was mostly his fault”; etc. The parallels to the sufferings of Kevin Shapiro, Boy Orphan, are right there on the surface to be picked up by any passersby.

Meanwhile the real Kevin Shapiro is dating three cheerleaders at once, drives a convertible, and has just been accepted into Princeton.

Finally, while meditating on the floor of a poultry slaughterhouse (the Dharma Ducks have been running out of places to practice their religion), our heroes achieve what a chapter title labels satori, or enlightenment. They realize that they have been wasting their lives on Zen, and that all this time they should have been focusing on…revenge! Revenge against Kevin Shapiro and Sigmund Yee and their high school principal. With their bloodthirsty vows, and with the implication that in the future the Ducks will emulate only Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the novella ends.

c. The third part: “The first chapter of The Dada Boys in Collitch, a novel to be completed sometime or other”

Ostensibly a lone chapter from a hypothetical novel that has never materialized, this section is still half as long as either of the two novellas that precedes it; in other words, it is the single longest chapter in the whole volume.

Our heroes have now hied to the hallowed halls of Martwist College—two of them have enrolled, and the other three come along because “Wild Dada Ducks stick together.” They are all now resolutely devoted to their “ultimate hero” Mozart, and have reverted to their old name (Wild Dada Ducks) under the assumption that Mozart would approve.

In college, the Ducks find what they never could in high school—a kind of community of the damned, made up of fat kids, queer kids, “obnoxious” kids, etc., as well as one violent and frequently naked self-proclaimed genius named John Holyrood. When the Ducks’ dorm room cum Mozart shrine is trashed in a John Holyrood-centered orgy, our boys face expulsion—but by that point they have already met Henrich Bleucher, a forest-dwelling leprechaun with a thick German accent and ambiguous supernatural powers who gives lectures about prehistoric cave paintings at an outdoor classroom cobbled together out of kitchen chairs and a ping pong table. Realizing they can get a better education from this freakish little hermit than from their lame college classes, the Ducks rob Holyrood at knifepoint and flee, to live as outlaws in the woods. Here their education can commence. End chapter one. End the third section. End the whole book.

d. The book in toto

The arc that the Dada boys’ story follows is only mildly unconventional. They suffer and squirm through the vagaries of adolescence, and end up the first chance they get abandoning the civilization that has betrayed them. If you except the fact that there are five protagonists and not one, it’s not so different from a canonical bildungsroman such as Knut Hamsun’s Hunger.

And yet the Young Adults volume consistently frustrates any attempt to read it as a coherent whole. Even though only the first part was ever published separately, the second and third parts retain the fiction that they are discrete, autonomous units: Dead End Dada spends an entire chapter recapping the events of Young Adult Novel, and the opening chapter of Dada Boys in Collitch summarizes (more rapidly) both novellas. Furthermore, Hunger may have had an “open” ending, as its protagonist, in true bildungsroman style, sails off to new adventures—but at least it’s an ending! Here comes THE END of Hunger, and you put the book down satisfied to have completed something. The Dada Boys in Collitch is just an opening chapter of a promised work. The one thing you have not done is finished reading…anything!

This is hardly accidental. When the Ducks put on a Dada play and read, card by card, a shuffled poker deck verrrrrry slowly—we are told that the audience (highschoolers trapped in a cafeteria) found it a frustrating experience. A Dada story should frustrate, should it not? Conventional YA novels come to a conclusion, but Kevin Shapiro, Boy Orphan reboots and goes on forever. As bonus material, Pinkwater includes extra chapters of Kevin Shapiro, Boy Orphan allegedly sent to him by young readers after the publication of Young Adult Novel. In one “fan chapter,” Kevin has his first-ever birthday party, and all the guests are poisoned and die. “How will I explain about the fiery angel that warned only me to eat nothing?”

e. A judgment

Young Adults is the funniest book written in the twentieth century, or at least one of the top five.3 I hope I’ve made that clear. We live in a particularly humorless time, and I’m sure many readers will find the Ducks too unpleasant, too “unprofessional” or too “privileged” or too whatever our particular bogeymen may be. In the Ducks’ defense, they’re reacting against a world gone mad—on the macro level of geopolitics, they claim, but really on a micro level in the sense that every authority figure or system they encounter is corrupt, hostile, mendacious, or evil, and often all four. If you were just looking for a nihilistic book with a bunch of fairly dirty jokes and a vague tie-in to Modernism, I would recommend this one. You’ll be satisfied.

But that is if you read Young Adults on its own. Young Adults is merely a great book, but that is scarcely all it is; rather, it is a deconstruction and a confession and an analysis of Daniel Pinkwater’s entire oeuvre.

This is where things get interesting.

Part II: The Structure of the Structure

Every single novel-length book Pinkwater wrote before Young Adults4 (and many he wrote after) follows an identical pattern. You can shoehorn his novellas into the pattern, if you want, as well, but the novels are clearer, and we don’t want to get bogged down in minutiae.

This is the pattern:

§1. A young man is dissatisfied with his life (sometimes suffering through a living hell, sometimes merely bored).

§2. He falls in with a slightly strange character.

§3. That character brings him into a world that is more than slightly strange. Somewhere around here we leave the fields we know.

§4. The protagonist has a mystical experience.

§5. In a state of enlightenment (or something!), the character returns to 1.

It would test the reader’s patience to endure my running through the plots of several more books, but look briefly at Lizard Music: Victor (the only Pinkwater protagonist this side of Charles the Cat to be deprived of a last name) is bored and listless when his family leaves for the summer without him (that’s item §1). He hooks up with the Chicken Man, a strange character based on a real-life Chicago eccentric (§2). Together they travel to an invisible floating island named Diamond Hard (§3), where Victor enters the House of Memory and has a unique experience he does his best to describe (§4). He brings home a stuffed animal he had lost somewhere in his childhood and a newfound desire to become something like the Chicken Man himself (annnnnd §5).

In Alan Mendelsohn, §1 is Leonard Neeble, and §2 is Alan himself. In Worms of Kukumlima, §1 is Ronald Donald Almondotter, and §2 is Sir Charles Pelicanstein. In Avocado of Death, §1 is Walter Galt (and his pal Winston Bongo), and §2 is Rat. You can work through these on your own.

But already you have whipped out your copies of Joseph Campbell and are insisting that this pattern is so ubiquitous as scarcely to need mentioning. This is the monomyth and blah blah Star Wars blah blah thousand faces. But Pinkwater’s books are unusual in that they never stop insisting that their heroes’ journeys are sometimes explicitly but always implicitly steps towards a transcendent, mystical experience. Perhaps the clearest explication of this experience comes in Borgel (the first Pinkwater novel published after Young Adults): therein Melvin Spellbound says, “I wanted to laugh. Or cry. I knew I could never figure out what was causing all these strong feelings in me. I wanted to stay there, looking at the shining Popsicle forever.” (This is more explicit in context; also, in context the Popsicle part makes sense.) But you can see it in Ronald Donald Almondotter’s search for Kukumlima (which one can only find when lost) or Leonard Neeble’s crossing over into Waka-Waka (which can only be achieved by meditation).

The meditation Leonard Neeble uses to reach Waka-Waka is heavily coded as Zen meditation, and indeed Leonard leaves for Waka-Waka from a garden festooned with Buddha statues. Buddhism, and Zen Buddhism especially, is all over the Pinkwater canon: The Snarkout Boys shop at the All Night Zen Bakery; Harold Blatt (The Last Guru) invests in the Zen Burger; psychic Lydia LaZonga (Baconburg Horror) goes to a Zen Chiropractor. Dueling Buddhist and pre-Buddhist sects such a Blong or the Silly Hat Order make frequent appearances. Before Harold Blatt invests in the Zen Burger he makes his seed money at the racetrack, betting on a horse named after the Buddha’s own horse (Kanthaka). Pinkwater, in his autobiographical works, has made it clear what a great debt he owes to his readings in Zen. His apprenticeship to sculptor Navin Diebold5 he codes as a Zen master/disciple relationship, complete with puzzling koans. When Pinkwater gets Diebold to read a copy of Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, Diebold exclaims, “Hell of a thing! I’ve been a Zen Master all this time and I didn’t even know it.”

I don’t want to press this too hard; certainly the Buddhist trappings are often just ornamental. But the mystical experiences at the heart of the Pinkwater novel are coded as satori frequently enough that the reader has to understand them through this lens. And I know I’m being slightly coy about what exactly a §4 “mystical experience” entails—but that’s part of the problem with mystical experiences! Georges Bataille wrote an entire book about transcendence (L’expérience intérieure) and I read the whole thing and didn’t understand a word of it.

One interesting aspect of these intérieure experiences as Pinkwater’s characters internally experience them: They’re often disappointing. Victor from Lizard Music is probably the only protagonist ever to be completely satisfied four stars would Zen again. Ronald Donald Almondotter meanwhile is threatened with a diet of nothing but crunchy granola forever, Eugene Winkleman (Yobgorgle) with a diet of fish flakes. The Snarkout Boys, like some kind of Lovecraftian narrator, learn of the cosmic peril that besets the earth and immediately fail to prevent or subvert it. Leonard Neeble drinks fleegix and it tastes “lousy.”

But afterwards Leonard Neeble, who had started the book in junior high school hell (§1) returns to our world from Waka-Waka and finds his place. “I was taking over Alan Mendelsohn’s old job.” As surely as Victor was seeking out the Chicken Man’s.

Part III. The work in the domain of the structure

This is, of course, not a review of a half dozen novels Daniel Pinkwater wrote in the ’70s and early ’80s. This is a review of Young Adults! So our job is to determine how Young Adults fits into what we might want to call the Pinkwater monomyth.

One thing to notice before we plunge in is that Young Adults is often a straightforward parody of tics or even scenes from these earlier Pinkwater books. Already mentioned is the fact that Pinkwater’s characters tend to flirt with Zen; and so the Dada Ducks declare it inferior to glorious revenge! Furthermore Pinkwater’s books often revolve around chickens, so the Ducks put on an unendurable play titled The Chickens of Uranus. The Balkan Falcon is a dark mirror of the Magic Moscow. Or: Leonard Neeble manipulates his therapist to get himself out of gym class,6 so the Dada Ducks try to manipulate their therapist—that’s when they’re publicly branded as onanists and assigned extra gym.

But such trivia is merely cute. More importantly, each of the three sections of Young Adults engages with our monomythical superstructure in unique ways.

a. the first novella, YNA

In Young Adult Novel, Kevin Shapiro is placed in the role of the Pinkwater protagonist at §1: He is a dissatisfied, alienated, antisocial nerd enduring high school by keeping his head down. This situation is unusual, because Charles the Cat is narrating the story,7 not Kevin Shapiro; and yet Kevin Shapiro, like any good protagonist, is the first character to appear in the book. In fact, the entire first chapter of Young Adult Novel is about Kevin Shapiro—it’s about how he’s a drug-addicted criminal who is murdered and fed to pigs (because it’s a chapter reprinted from Kevin Shapiro, Boy Orphan), but it’s still about him.

Kevin Shapiro meets some slightly strange characters (§2), and these are the Dada Ducks. In other words, while previous books had been from the (first-person) point of view of the alienated young man (§1), Young Adult Novel is from the point of view of the strange characters (§2) themselves.

And in this book, and in this book alone, the alienated young man wants nothing to do with the strange characters! He is openly hostile to them. “I’ll punch out your face, see?”

This hostility throws our monomyth off its monorails. Kevin Shapiro’s epiphany is not an internal one, but rather an elevation by popular acclaim to unprecedented power. “I think he may be God,” the Honorable Venustiano Carranza (President of Mexico)) says of Kevin Shapiro on first meeting him, and indeed Kevin assumes the status of a god-king whose “word was law.” But Kevin is a cruel, vengeful god whose sole motivation is to humiliate the Dada Ducks. The structure cannot continue.

Kevin barely makes it to §3, and if he goes further, he’s not telling.

b. The second novella, DED

By Dead End Dada, the Ducks, more alienated than ever, have assumed the role of §1. This is a reversal of other novels, in which the §1 figure takes the “old job” of the §2 figure. Our alienated Ducks only need to find a good §2 and they’ll be well on their way to experiencing a proper Pinkwater structure, and not the travesty of the first novella.

Unfortunately, they find no strange character. The individual they set their sights upon, Sigmund Yee, wants (like Kevin before him) no part of this plan. He, too, is openly hostile to the Ducks. (“Go do teenage crimes somewhere else!…Leave Yee alone!”) Once again the structure falls apart. The Ducks get no closer to §3 than a laundromat or a poultry slaughterhouse.

c. The chapter of an unfinished work

The Ducks come to college having failed twice to experience properly the book they are in. They are like characters who have blundered through a mystery novel without either leaving or finding any clues; characters in a romance novel who neither fall in love nor break a heart. They are genre misfits.

And at first it seems like they’re headed for a third strike, because the §2 they encounter is John Holyrood, a filthy, mooching poser who brings them nothing but trouble. There’s every evidence that he’s not even that strange—he’s a normie faking it to get girls and free liquor.

But Holyrood is a false flag. Holyrood is a red herring. As should be clear from the thorough Cliff Notes trot above, with the Holyrood situation falling apart around them the Ducks encounter the real deal in Henrich Bleucher. Bleucher does not hate the Ducks (as Yee or Kevin Shapiro did). Bleucher is not trying to use the Ducks (as Holyrood did). Bleucher leads the Ducks off into the woods to lecture them about art. Igor suggests that he already knows there is more to Bleucher than meets the eye—but of course there is! Soon, presumably, the Ducks will be abandoning reality altogether, well on their way to a mystical experience—but before that happens the book ends.

d. Come up with a clever title here. Don’t forget!

In this way the Ducks finally succeed, if only off the page, or in the hypothetical pages of a never-written work. It takes them three (or possibly three and a half) tries, but they are finally participating in the Pinkwater monomyth.

Later in his career, Pinkwater more and more often offered art as a way of experiencing whatever mystical event underpins §4. Recall that the soi-disant “Zen Master” Navin Diebold is a sculptor. In Pinkwater’s only personal account of a mystical experience (as related in the autobiographical Fish Whistle), it comes to him while he is contemplating a de Kooning painting.8 When Victor reappears years later in the novel Bushman Lives! he is the curator of an artists’ collective. In Chicago Days, Hoboken Nights, Pinkwater imagines a Vietnamese artist known as (significantly?) Duck having “ascended to Nirvana” because he managed to “completely comprehend the true nature of reality in the clear light of Buddha.” Pinkwater mentions that Duck is a better artist than he is.9

The Dada Ducks start out dedicated to art, specifically Dada, and end up dedicated to art, specifically Mozart. Is Dada truly (as the title claims) a dead end? Do the Ducks need Mozart to move along towards the mystical experience? Is it significant that, although he promises to speak on diverse academic subject, Bleucher’s opening lecture is an art lecture?

Perhaps it is foolish to look any deeper into what is, ultimately, “a Dada story.” Or perhaps a mystic always looks deeper. Three-quarters of a millennium ago, Izzidin Al-Muqaddisi wrote: “The man who fails to extract the significance from the sharp creak of the door, the buzzing of the bee, the barking of the dogs, the industry of the insects in the dust; he who knows not what is signified by the motion of the cloud, the shimmer of the mirage, and the shading of the mist; this man does not number among the perceptive ones.” I probably should have looked for a Zen quote instead, but let it stand.

e. “Salvabitur vix justus in die judicii; ergo salvabitur.” –Langland

Every once in a while a friend will recommend an anime to me, but grudgingly admit that you have to sit through twenty or thirty hours of mediocre episodes before it gets really good. There are comic book series I have pitched, in vain, to people in the same (wade through fifty poor issues to earn the next fifty good ones) terms.

If you want a full appreciation of Young Adults, perhaps it is true that you should read a half dozen earlier Pinkwater novels, and then go on to read another dozen later books. You will never again find a work, I think—not Nabokov’s Look at the Harlequins!, not Bukowski’s Pulp—that so aggressively comments on and subverts a writer’s oeuvre. Victor’s life would have been very different if the Chicken Man had just been a jerk; or a loner; or an opportunist. Young Adults acknowledges this, and runs this plot that Pinkwater clearly loves so well through the wringer three different ways. But there is still a note of hope: The Dada Boys have to struggle through two books just to reach the spot Victor or Leonard Neeble start at—but they still ascend.

And that is the note of hope for prospective readers who do not want an assignment of nearly a score of books to plow through: As I mentioned, even when read alone and in complete ignorance of any other Pinkwater book, Young Adults is still one of the five funniest books of the twentieth century, so maybe just start there. You’ll want to keep going.

Who really killed JFK?

On the fifth page of Superman #1, Superman himself says to a woman, “I thought you might be interested in learning I know that you killed Jack Kennedy.” She killed him, according to Superman’s theory, for “two-timing her,” which is perhaps a plausible motive, given Kennedy’s philandering; surely Superman’s theory is no stupider than anything Oliver Ston…

This structure is present in the 1991 mass market reprint of Young Adults. An earlier (1985) edition contained ~80 pages of supplementary material, most of it in the form of bitmappy comic strips illustrated with a very crude and early version of MacPaint. The comics are funny and in some cases overtly Dada-inspired (and in other cases just about Mozart being a bad superhero), but they do not inform my reading, so I have ignored them. Consider this a review of the mass market edition only.

Not the author of but the master of the author of the cookbook is Alan W. Watzuki, his name a portmanteau of two of the most prominent popularizers of Zen in America: Alan W. Watts and D.T. Suzuki. Alan W. Watzuki, we learn, “died of gastroenteritis…at a relatively early age.”

I don’t know, maybe (not in order):

Young Adults

Shirley Jackson, Life Among the Savages

David Sedaris, Barrel Fever

Martin Amis, The Information

Barbara Robinson, The Best Christmas Pageant Ever

?

The novels in question are:

Lizard Music (1976)

Alan Mendelsohn, the Boy from Mars (1979)

Yobgorgle: Mystery Monster of Lake Ontario (1979) [The weakest fit, in my opinion.]

Java Jack (1980) [Co-authored with Luqman Keele.]

The Worms of Kukumlima (1981)

The Snarkout Boys and the Avocado of Death (1982)

The Snarkout Boys and the Baconburg Horror (1984) [A sequel, so a little different.]

Notice that many later books, such as Borgel (1990) or The Neddiad (2006) follow an identical pattern.

The novellas I mention (sub) would include Wingman (1975), The Last Guru (1978), and the Magic Moscow trilogy (1980–82), but these are not really considered (although occasionally referenced) in this review. But you’ll find they more or less fit.

Navin Diebold is Pinkwater’s thinly fictionalized version of one David Nyvall, Bard professor.

Technically Neeble manipulates the therapist into getting him out of school, with the eventual result that he is transferred out of gym class. Don’t you Encyclopedia Brown me, here!

All seven novels listed above (although not all the novellas), as well as almost every novel that follows, are narrated in the first person. Baconburg Horror, admittedly, has some third-person chapters, as an homage to Moby Dick, Pinkwater’s favorite novel and arguably one that fits his own particular monomyth (Queequeg is §2).

This incident is recapitulated fictionally in the story of Harold Knishke in Bushman Lives! (the novel referenced in the next sentence).

I didn’t want to overburden this paragraph with examples, but I also couldn’t resist pointing out that Robert Nifkin, trapped in a “realistic” novel (The Education of Robert Nifkin), and therefore unable to experience some Popsicle metaphor for transcendence, ascends quite literally from the lowlands of Chicago to Bard College (disguised under the most tissue-thin veil). Bard College is where Pinkwater studied art under Navin Diebold.

i will admit up front that i basically found this blog post by accident (decided to google "kevin shapiro" "grape nuts" today like i do every three years or so and i happened to find a post that was less than a week old) but i really enjoyed it and think you hit the nail on the head. really really enjoyed it. i'm really happy to have realized through your help the wild dada ducks are these frustrated life changing event looking for a protagonist. love it all. really good blog hal. thanks.

I'm sorry you didn't win the prize, but future readers will recognize this work as a cornerstone text in the too-narrow field of Pinkwater Studies. Your argument for the importance of YAN as both Rosetta Stone and funhouse mise en abyme is totally persuasive— what Tolkien did for Beowulf, you've done for Charles the Cat.

I'm also stuck by your observation that, for P's protagonists, the moment of enlightenment is often dissatisfying. In fact—and I'm writing a short paper about this—his heroes are often sidelined (eg Lizard Music and Borgel) or unable to report what happened (Neddiad) at what should be the climax of the novel. What this means is something I'm still trying to work out.

Speaking of The Neddiad, have you noticed how many specific name drop references it makes to the greater Pinkwater Cinematic Universe? Aside from the usual structural echoes, Colonel Ken Kremwinkle's in there, as are Hergeschleimer's Oriental Gardens and the Inept Eft. Even Yggdrasil Birnbaum feels like a re-skinned Rat. A loose-limbed and very interesting novel.

Anyway, thanks for this great work — I know I'll be drawing on it in the future.