(I, myself, write books professionally, and I hope you will sample them—you can find a generous list on amaz0n, on bookshop.org, at b&n, or in your local library. This will not be the last time I mention this fact. I am also tippable, for the generous, here. Upcoming appearances: July 15, 6–7:30, author talk, Old Stone Church, 251 Main St., East Haven CT) | July 19, 10–3, Book Walk, Main St., Old Wethersfield CT.)

About Daniel Pinkwater (henceforth DMP) I know nothing and everything. I say nothing because I’ve never met the man. I’ve never spoken to his friends or relatives. My few attempts to flirt with him online have been failures (as such flirtations tend to be). Whatever deeds he has done in his life await the pen of a hypothetical future Boswell or more likely, as is the fate of most deeds, the oblivion of time.

But every man husbands inside his breast a secret soul, which some eschaton or another is always threatening to reveal but which can be perceived on this side of the veil solely through the intermediary of art. I know a lot about DMP’s art—the literary art of his published books, specifically. That’s what we’re here to talk about.

DMP wrote or co-wrote (depending on how you count) about 105 books in his career, and what follows is a ranking and discussion of 104 of them.

The remainder of my methodology I have relegated to a footnote1 so as not to tax the patience of the reader.

Without (as they say) further ado, the entire DMP canon, best to worst—scroll down to your favorites and get mad at me!:

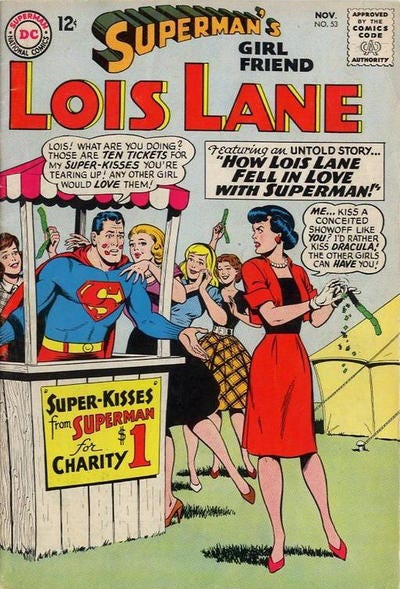

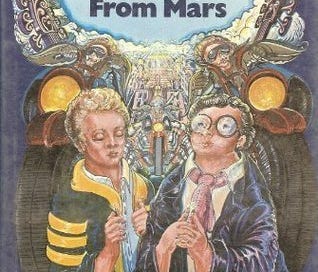

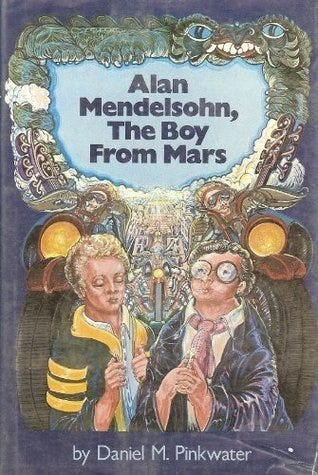

•1 Alan Mendelsohn, the Boy from Mars (1979 middle-grade novel)

[Two junior-high students gain psychic powers to 1. baffle their classmates and idiot teachers and 2. travel to other dimensions.]

Alan Mendelsohn, the Boy from Mars (permit me to here at the beginning to proffer a smidge more of plot outline) is the story of young Leonard Neeble, suffering through a terrible junior high experience until he meets a weird classmate known as Alan Mendelsohn; Alan claims to be from Mars (or alternatively the Bronx). Together Leonard and Alan frequent used bookstores, and lo in an occult shop they discover the secret to psychic powers and eventually interdimensional travel. They have an adventure. Leonard finds peace.

I’ve argued elsewhere that many or most of DMP’s books follow a similar structure: An alienated young man meets a weird character, gets drawn by him into an ever-weirdening world of weirdness, and finally achieves some kind of transcendent experience . You will notice that this monomyth, this DMP-standard plot structure, also fits Alan Mendelsohn; so why, then, is the book special? What makes Alan Mendelsohn better than its superficially similar rivals? Why (specifically) is it number one on this list?

One thing may be that Leonard, the narrator of Alan Mendelsohn, starts from a lower point than any other DMP protagonist. He’s genuinely suffering! Maybe the Dada Ducks from Young Adults (#2) are also suffering, but they are clearly suffering intentionally, gratia artis. Leonard is unwillingly uprooted and deposited in the hell that is West Kangaroo Park. Uprooting is a classic opening to a novel, and DMP’s canon is filled with uprooted protagonists (Robert Nifkin from The Education of Robert Nifkin (#4), Nick Itch from Looking for Bobowicz (#100), Neddie Wentworthstein from The Neddiad (#15), Jules McSchwartz from Jules, Penny, and the Rooster (#35))—but they all end up better off than they were before relatively quickly. Chicago, Hoboken, L.A., and the ’burbs (respectively) are good to them. Leonard (on the other hand) leaves friends, family, and a neighborhood he loves to find himself friendless, miserable, and failing out of school. The stakes are higher here than in any other book (even Nifkin, which comes second)!

The driving theme in almost all of DMP’s work is (as alluded to above) the quest for transcendence—“the blessings of enlightenment” one character calls it in Adventures of a Cat-Whiskered Girl (#26). The quest is often driven by a dialectic or conflict between two proposed routes to transcendence, which could be simplified as meditation and art, or the way of the guru and the way of the artist. Perhaps in Alan Mendelsohn the scalepan is tipping towards guru: Leonard uses (thinly disguised) Zen meditation to find adventure and yoga to find happiness, while the Waka-Wakans discover that pure aesthetics lead not only to cowardice but also, which is worse, to bad art. Perhaps a rival reading will insist that meditation brings Leonard nothing but boredom and lukewarm fleegix, and the Waka-Wakans’ mistake was in consuming art without producing it. I’m not here to adjudicate your readings. I don’t want to get bogged down in this stuff (yet).

Generally (by my math) a DMP book is two-thirds setting, one-third theme, one-third jokes, and maybe some plot. Alan Mendelsohn is less jokey than later books while still being very funny; it also has one of DMP’s most satisfying plots (insofar as there are coherent conflicts and difficulties, and they are all resolved at the end). We’ve already addressed the theme, so let me propose that the best thing about the book is the setting: I don’t just mean the city of Hogboro, a funhouse-mirror version of Chicago (more on this later), or the nightmarish Bat Masterson Junior High. I mean a world in which two friends can learn secrets, cause havoc, and have adventures. I mean that the best place to find adventure is a street full of used and weird bookstores, and the best place to leave this earth is an abandoned, forgotten, and overgrown exotic-garden tourist trap—and they’re all here!

Unlike later DMP books, in which adult advisors (Chicken Nancy in Cat-Whiskered Girl, the Yorkshire witch in Dwergish Girl (#31), almost every grownup in The Neddiad) are benign, everyone in Alan Mendelsohn is on the make. Samuel Klugarsh is three-fifths sheer fudge, and only accidentally does he fail to defraud our heroes. Clarence Yojimbo is not about to give away the secret to Hyperstellar Archaeology. Dr. Prince is a sap if not a fraud. You get the feeling that everyone sees Leonard and Alan as a “mark” except William Lloyd Floyd, whom Alan sees as a “mark.” This is merely another way of saying that Leonard and Alan are treated as adults, the most exciting moment in the life of a junior-high student. And the coda, where Leonard comes into his own; and is then given the promise of future adventure…this is the world I would wish to live in.

DMP has a great many wonderful books, and I won’t kick if you (dear reader) have a different favorite, but Alan Mendelsohn is the book for me.

•2 Young Adults (1985 YA novel, or novellas, or weird collage of stuff)

[Six friends devote their lives to art despite the carpings of a philistinistic world.]

I’ve written about Young Adults at some length before, and I’ll try not to repeat myself—but of course I have to justify placing a book at the #2 spot, especially when that book is hardly even a book, but rather a miscellany. The bulk of Young Adults is comprised of three parts: two linked novellas (one previously published as a separate volume) and a long chapter purporting to be the first of an actual novel. Just as things are getting started…the book ends. These three parts are in some sense conventional narratives, if we stretch the meaning of the word conventional and ignore the fact that extra chapters of an endless Dada young adult novel find their way to be scattered in here and there.

Mixed in around and between these three conventional parts are a collection of crude Dada comics and illustration galleries, plus a lengthy surreal attack on DMP’s art and character apparently written by a friend of his. The book was reprinted without all of these extra parts, and I didn’t notice for years.

The conventional narrative—or three conventional narratives—tell three stories in the degraded lives of six teenage friends who alternate between elevating artist and guru in their desperate attempt to wring some meaning from the suburban hellscape they live in. It goes poorly.

And none of this should work—I mean, as a book. The characters are not even characters, as their only defining features are how tall and how thin they are. The plots—and remember, there are three separate plots for three separate narratives—are all slim and implausible.

But none of that matters. “This is a Dada story.” Modernism 101 is that you cannot grapple with the chaos of modern life with classical forms. The Dada Ducks—our heroes—can express neither their art nor their pain constrained by an Aristotelean story arc. As I said before, these are the only characters that suffer as much as Leonard Neeble, and if the suffering is almost 100% their fault, surely this just makes it nobler.

It’s also one of the funniest books ever written. I understand that Modernists have subverted narrative in the past, but if Kotik Letaev or In Parenthesis had made me laugh this much, I’d be writing about them instead of this book.

Probably you should eventually go read the really very long piece I wrote about Young Adults, but do it later, because Lizard Music is next on the list.

•3 Lizard Music (1976 middle-grade novel)

[Young Victor is left alone by vacationing parents and an irresponsible sister, and soon finds himself tracking down clues, absorbed through late-night television, about a civilization of intelligent anthropomorphic lizards.]

Lizard Music is DMP’s first novel (I consider Blue Moose (#59) and Wingman (#10) to be novellas), and he hit the ground running. It features what is in some ways DMP’s most polished or conventional plot. The “call to adventure” is carefully set up, with Victor first isolated from his regular life and then slowly realizing that something weird is going on in the world—other DMP books move at such a fast clip that you might not notice that the action in many of them is precipitated by the narrator just meeting some guy at random. Although many of DMP’s novels build to an absurd or surreal conclusion, never again would the conclusion be as satisfying as the chicken-obsessed lizards of Diamond Hard.

For that matter, no DMP protagonist would have a transcendent experience as beautiful as Victor finding his squirrel in the House of Memory. If he had not brought the squirrel home I would have thrown the book in the trash, but he brought the squirrel home and so I love the book.

Most DMP protagonists are more or less interchangeable, and I think even a close reader would be hard pressed to distinguish between Leonard Neeble (#1) and Walter Galt (#7 & 30) and Robert Nifkin (#4) and Neddie Wentworthstein (#15) and Harold Knishke (#8) (etc.) outside of the specific lineaments of the situations they find themselves in. This is not to say that DMP does not create memorable characters; in fact, he excels in creating memorable characters. One of his most memorable is the narrator, who appears in a dozen books under a dozen names! But Victor is different. Victor is, I think, the most practical and proactive character to narrate a DMP book. DMP’s narrators are always up for adventure, but Victor seeks it out. He needs no Alan Mendelsohn or Winston Bongo (from Snarkout Boys (#7 & 30)) as accomplice; for that matter he needs no Osgood Sigerson (also Snarkout) or Melvin the Shaman (Neddiad (#15))—Victor follows clues on his own.

Needless to say, one of DMP’s other most memorable characters is the Chicken Man, a real figure from Chicago folklore who appears in three DMP novels and one book of essays, but here in Lizard Music for the first time. Less sinister than his appearance in Snarkout Boys, less purely mad than he is in Bushman Lives! (#8), the Chicken Man in Lizard Music is a strange but wonderful combination of Gandalf, Don Quixote, and Lord Buckley.

Lizard Music lays out the basic DMP landscape quite starkly: There is a preterite and an elect. The preterite are possessed by aliens. The elect learn to appreciate musical lizards and dancing chickens. The scene in which Victor realizes, while watching a talk show, that American pop culture is indistinguishable from the aftermath of an alien invasion is at once hilarious and harrowing. If DMP’s texts are an attempt to articulate a mystical experience, they are also an attempt to delineate a roadmap out of the hell that is life among pod people. This theme he returns to again and again in his later novels, but it’s all right here in the first.

The character Victor also features in another, later book, and when he reappears he is the director of a secret art collective. For this to happen he has to cross time, space, and (I do not say this lightly; it’s all there in the text) the other. But he also has to believe in art. DMP’s texts, more and more as time goes on, will be simultaneously art themselves and a finger pointing at art. But it starts here in Lizard Music.

•4 The Education of Robert Nifkin (1998 YA novel)

[In 1950s Chicago, a young man fails out of public high school but finds his place in a much sketchier private school.]

Many of DMP’s earliest books tend to take place in what one might call the real world: Hoboken (Hoboken Chicken Emergency (#46)), Rochester (Last Guru (#29)), or Washington Heights (Wingman (#10)); then, after a spate of novels set in some kind of fantasy America where Chicago is called Hogboro or Baconburg,2 DMP returns to reality. There are exceptions to this schema—Yobgorgle (#37) is in Rochester, Lizard Music (#3) in Hogboro—but it helps me, at least, pin down DMP’s books in place and time. It helps me sort.

When The Education of Robert Nifkin came out in 1998, it was DMP’s first novel for young readers in eight years, following Borgel (#11) (which takes place nowhere and everywhere). It is set in, and is about, Chicago. Almost all DMP novels are bildungsromans, but Robert Nifkin is the most bildungsromany. It is perhaps not DMP’s most savage but certainly his most sustained attack on public schooling. Yes, it takes place in the real world, but it’s a version of the real world in which Kevin Shapiro (boy orphan from Young Adults (#2)) can be “Professor of Art History at Miskatonic University.”

Good old Miskatonic U. is, of course, a reference to a different creator’s work; but Nifkin’s real-life Chicago abounds also with cameos from DMP’s own. Artifact smuggler Samuel Klugarsh from Alan Mendelsohn (#1) and master criminal Wallace Nussbaum from the Snarkout Boys books (#7 & 30) both appear, and their chronologies line up fine with their established lives (unlike Kevin Shapiro’s above). William Lloyd Floyd and (unnamed) the Mad Guru are there, presumably because these are real denizens of the Chicago of DMP’s youth (and Floyd reappears, himself unnamed, in Bushman Lives! (#8)).

But we’re not here to talk about Chicago. We’re here to talk about education! Robert Nifkin (nifkin, where I come from, is slang for perineum; just saying) has to get educated.

One can view the title with some degree of irony; the entire book is a college application (“use additional sheets of paper as needed”—one of the driest of witty intros to a novel), so perhaps the education comes later, after the application essay/book is handed in and accepted; in other words after the book is over. But Nifkin is also straight-up about Robert’s education. Like a Saul Bellow character, Robert can learn how to be a slightly crooked hustler (“that’s the Chicago way,” as they say in the Untouchables) before his book-learning kicks in. But he also manages to book-learn, all while attending a broken-down parody of a fancy private school. The Wheaton School defies casual description, with its Southern-gothic decay and pornographer teachers; it’s not a place that demands that students learn, but significantly it is not a place that forbids it, either. (It encourages comparison with the unorthodox education offered to the Dada Ducks by Henrich Bleucher at the end of Young Adults (#2).)

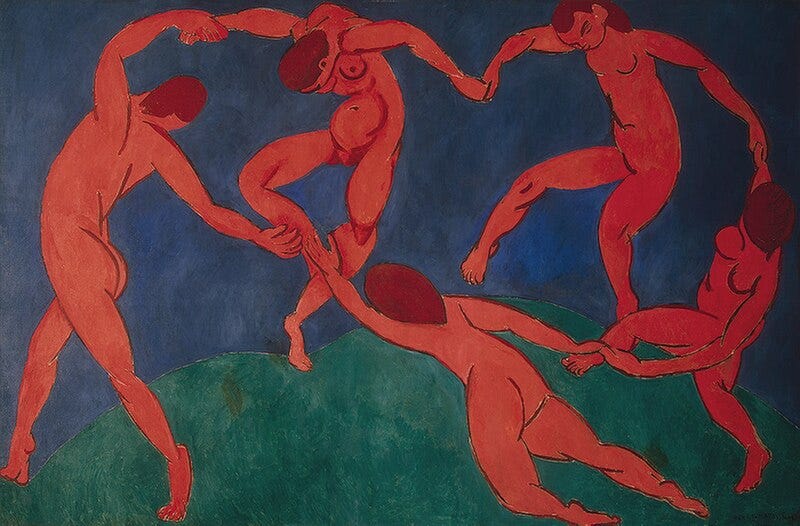

I mentioned before that a DMP novel is a roadmap out of the hell. This is Robert’s true education. He knows what hell is—Riverview High School (Harold Knishke from Bushman Lives! also attends, slightly later) or, perhaps, the tacky bourgeois world of his parents—and various people offer him ways out. Sergeant Gunter offers communism. Clifton Fadiman (“no relation”) offers life as a hoodlum. Jack Evergreen doesn’t so much offer as disappear down a chess hole, but surely that’s (“the Luzhin defense”) an option. Robert Nifkin reads books (he tells you which books) and looks at art (he tells you which art) and watches movies (he tells you which movies) and listens to music (Odetta; he tells you) and presumably will escape to a thinly veiled analog for Bard College (here called St. Leon’s; a Bard alum explained the joke to me). But his secret, of course, is that just wandering around Chicago he had already escaped. Chicago was all he needed. Riverview was terrible, but Chicago was good to him.

Unlike just about every other DMP protagonist (I’m aware there are a couple other exceptions), Robert Nifkin never experiences a moment of transcendence. This is a naturalist novel, true, but even James Joyce gave his characters epiphanies. I should be disappointed by this fact, but I’m not. Robert Nifkin is trapped in the real world, and the real world is all he gets, but the real world is also his way out of it.

And this burden—of abandoning his usual novelistic structure, of being unable to fall back on some mystical experience—forces DMP to give Robert Nifkin some real bildung in this roman. Nifkin achieves an almost impossible feat: Robert matures and grows and learns and, you know, comes of age; but—and this is the wonderful part—only a little. Robert Nifkin is ready for the next step, and no more. He is now (in the words of his faculty advisor) only “slightly repellant.”

Knut Hamsun’s Hunger is the story of a callow youth who eventually works himself up just enough to go to something else…and that’s the closest book I can think of to Robert Nifkin. Except Nifkin is funnier, more hopeful, and has a lot more Chicago in it than Hunger does. (Also DMP appears to be less repellant than Knut Hamsun.)

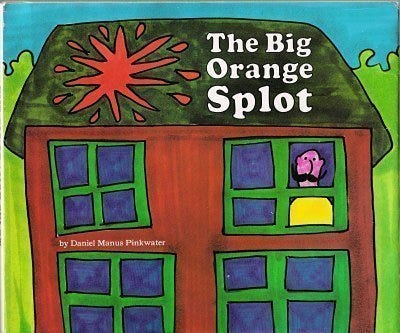

•5 The Big Orange Splot (1977 picture book)

[When Mr. Plumbean’s perfectly neat house gets slightly marred, he decides to shoot the moon and paint it in an absurdly colorful manner.]

Far and away my favorite of DMP’s picture books is this early charmer. It features an overt moral, which is usually death to any text, a children’s book especially, and the moral here is do your own thing, which is somehow even worse. But the insane delight the characters take in doing their own thing is both infectious and bonkers. None of this should work. All of it works (“no one knows why”).

On a dull street of identical houses, the kind Pete Segar would make fun of in “Little Boxes,” an accidental glitch in the uniformity inspires pure freedom and chaos. Mr. Plumbeam’s (eventual) house is the most splendid of eyesores. The rest of the block is even crazier, to the extent that probably some of the houses are completely unlivable, even if theoretically they could stand. So it goes.

Having people celebrate individuality by chanting a cultlike mantra is a strange choice, but it just comes across as fun. This whole book is fun Probably do not let your neighbor actually keep a pet alligator. Or do, I guess. I’m not your boss.

Note the constant stress upon the reader occasioned by saying the word Plumbean, with its three bilabial consonants followed by an alveolar /n/. The word perpetually strives to resolve itself into *Plumbeam, which would keep the bilabial pattern going. I imagine this stress is how the pre-splot Plumbean felt, desperately trying to keep his street neat despite the rainbow-explosion nature of his dreams.

My young son’s favorite DMP book, as he will tell anyone who asks. Certainly one of the all-time best picture books.

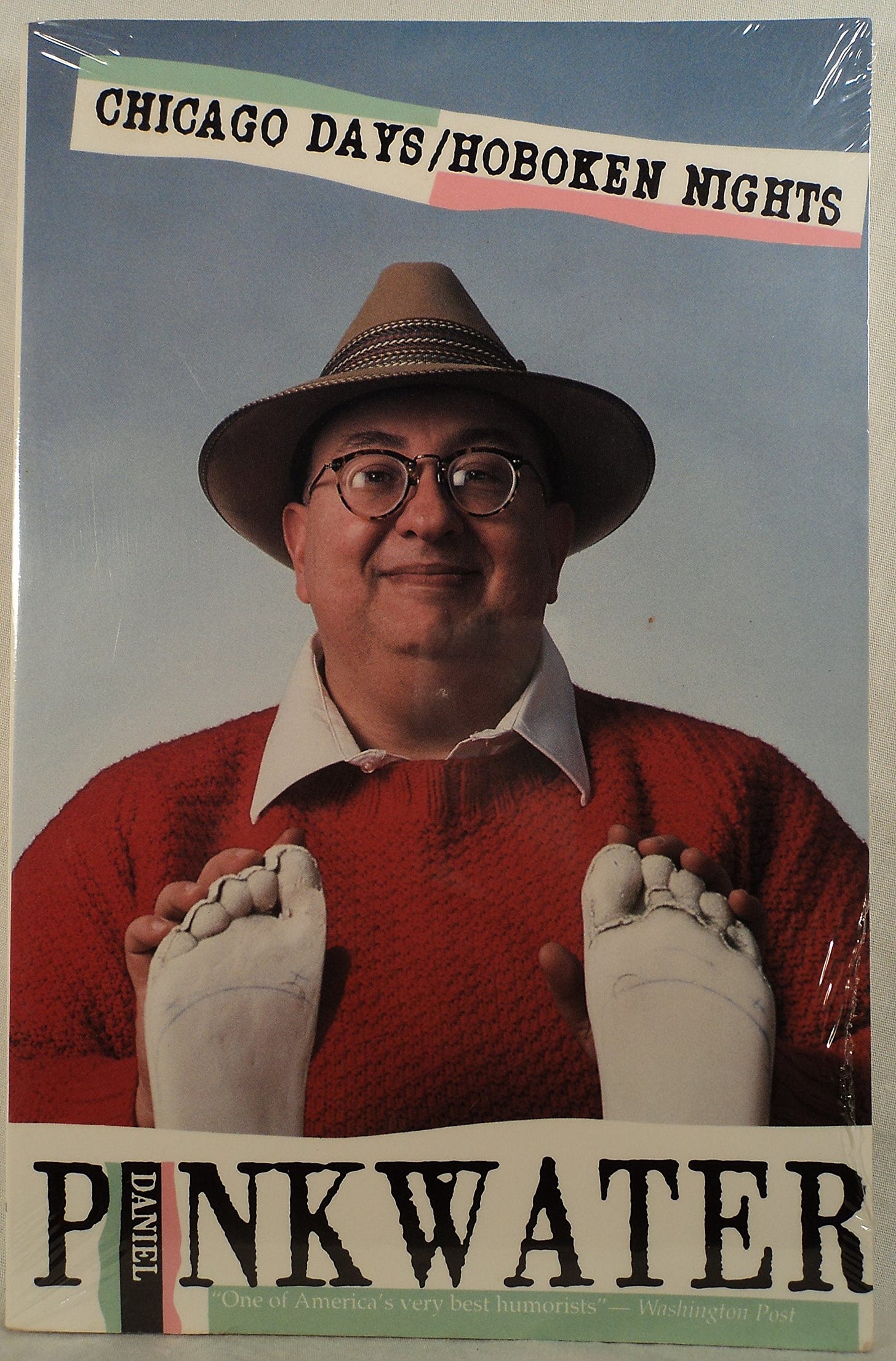

•6 Fish Whistle: Commentaries, Uncommentaries, and Vulgar Excesses (1989 essay collection)

[A collection of humorous essays, most of them having originated as radio pieces broadcast on NPR.]

First off, the titular essay (“Fischvistle”) is the funniest essay ever written, so even if the rest of the book was trash, or lorem ipsum nonsense, this book would still rank high. “Fischvistle” is the funniest essay in the book, and it’s the funniest essay in any book, and I find this strange because I cannot put my finger on why it’s so funny. When I first read it (as an adolescent) I thought “Compass, compass” was the choicest part, but now I think “Son, I want you to invent a fish whistle” is the choicest part. I guess it’s a specimen of dialect humor, but less pronounced than, say, Milt Gross. Hyman Kaplan is funny, and Milt Gross is much funnier, but “Fischvistle” is the queen of them all. Just dynamite stuff.

The rest of the book is also great! It’s funny, but it’s not as funny as “Fischvistle” (nothing is), and I don’t generally read DMP just for funny. A lot of people are funny. Erma Bombeck is funny, but when was the last time I made a list and put Erma Bombeck at #6? The essays (most of them radio pieces, reformatted for print) that are straight-up humor essays, like Andy Rooney bits, are the weakest parts!

But many of the essays are autobiographical, and DMP’s life has been like nothing anyone but DMP could imagine. It’s pretty clear that a lot of DMP’s fiction is autobiographical, and by my estimate every DMP narrator in every novel written between Alan Mendelsohn (#1) and Neddiad (#15) (and at least one outside this parameter) are just incarnations, variously obscured, of young DMP—but you’ll be surprised to learn just how very autobiographical that fiction has been, how unobscure those incarnations are! Harold Knishke’s experience with de Kooning’s Excavation (#8), the Snarkout Boys’ experience at the Laurel and Hardy film festival (#7), Leonard Neeble’s Uncle Boris and his adventures with a film camera (#1)—they are all, mutatis mutandis, true.

When characters are revealed to be based on real people, DMP gives them “real” names that are scarcely more plausible, or less DMPish, than their fictional counterparts: Clark Gomez (from Bushman Lives! (#8)) appears (in Fish Whistle) as Lance Gonzales; Davis Davisdavis (from Artsy-Smartsy Club (#60)) appears as Herman Hermann—in other places, such as the introduction to Four Hoboken Stories, DMP suggests that his real name may be David Davis, which appears to be the emmis; Madame Zelatnowa (from Alan Mendelsohn (#1)) appears as Sonia, and…well, Sonia is perfectly plausible. Actually her name might just be Sonia Zelatnowa. What do I know?

DMP has always excelled in creating (or evoking) an exciting world, a world one might want to live in, and what if that world were our world already? The Chicken Man and the E.J. Sperry Thought Factory and Bughouse Square and especially the Snark (actually the Clark) Theater are all (in some sense and of course filtered through a collection of scarcely fact-checked essays) “real.” “Sometimes I feel that my whole purpose in life is to tell people who might not have seen it that such a place as the Clark existed,” DMP writes, and that’s something we’ll return to later. If your life seems stupid and pointless (as it probably does), isn’t it pleasant to think that somewhere out there people are making art and/or listening to Mozart and/or scrawling FREE JOMO KENYATTA on a building? That dogs have some kind of pseudo-psychic bond with people? That one can get better at art through crypto-Zen practices? That small experiences—visiting a Japanese temple or the Art Institute of Chicago or building a model airplane—can change you for the rest of your life? Some of that is plausible, isn’t it?

Every story ever told presupposes a world, and the world DMP supposes in his anecdotes is simply better than ours. UNLESS IT ISN’T! UNLESS OUR WORLD IS THIS ONE! For that reason alone, even if it had no other virtues (which it does: “Fischvistle”), this would be an exciting book.

The two great disappointments of my life are that 1. I never thwarted smugglers (as boy heroes used to do in the old books) and 2. I never lived the DMP life. I put in a solid effort at the latter: I moved to Hoboken; I hung out with artists; I listened to classical music. I’ve had some weird times—at the homemade-flamethrower show, or the time I helped attach, with a hole-punch and string, an octopus to a robed man’s face so he…well, it’s a long story. I had a good time. But I mostly had a good time locked in an apartment, sipping tea and discussing books with friends. I went to Beanbender’s, but it was full of posers. I went to Maxie’s, but they told me to buy something or get out. I went to the College of Complexes and they wouldn’t even let me through the door. Maybe I was lacking, or maybe it was the times: DMP went back to the Clark, and it was a porno house. Maybe the whole world is a porno house now.

But for a while, after I read Fish Whistle and before I grew up and saw what the world was like, I believed.

•7 The Snarkout Boys and the Avocado of Death (1982 middle-grade novel)

[Two high school chums who sneak out at night to watch old movies find themselves plunged into a kidnapping plot involving a master criminal and an intelligent avocado.]

The first (of two; the apocryphal third volume never appeared) Snarkout Boys books is The Snarkout Boys and the Avocado of Death, DMP’s love letter to old movies. Walter Galt and Winston Bongo (the titular boys) consume a steady diet of weird B or classic films, and if the adventure they get wrapped up in involves plenty of Dr. Mabuse-type motifs and pulp cliches…well, a lot of DMP books do, too, so it’s hard to tell if this one leans more heavily into it or not. The butler did it. The plot is, perhaps for the first but certainly not for the last time, openly nihilistic (as is fitting with the literary reference in the title: “The snark was a boojum, you see”).

As is so often true, the setting is the true hero of the book. Baconburg is, as already noted, another stand-in for Chicago, with the Clark theater reimagined as the Snark, the Newberry Library as the Blueberry Library, and Chicago’s Washington Square Park even more overtly as Bughouse Square. Here narrator Walter finds that his true calling is sneaking out of the house to watch movies, dine at all-night eateries, and solve crimes. The implicit metaphor of North Aufzoo Street is one of my favorites: Upper North Aufzoo Street is a boring and lifeless thoroughfare, but under it runs Lower North Aufzoo Street, “the city beneath the city” where on the one hand Romani, screevers, and buskers ply their various romantic trades and on the other hand the delivery men and maintenance workers ensure the the actual (upper) city continues to operate.

For many people, this book will be remembered for the reappearance of fan favorite the Chicken Man. This reappearance is not the first doubling in DMP—that would probably be news reports of the president having a cold (from Lizard Music (#3) and Fat Men from Space (#51)), the city of Hogboro (from Lizard Music and Alan Mendelsohn (#1)) or the concept of Blong Buddhism (from Last Guru (#29) and Alan Mendelsohn) depending on what you count—but it’s certainly the first major character doubling, of the sort that non-obsessives might notice, and it certainly hints that many or all DMP books might be taking place in a shared universe. DMP’s fondness for reusing, apparently at random, uncommon names such as Papescu, Nussbaum, and Bogenswerfer3 can make it difficult to tell if someone is reappearing or just coincidentally sharing a name—security guards at the Hogboro Zoo (Lizard Music) and the Baconburg Museum (Avocado of Death) are both named Anolis, and I assume they’re the same person but really who knows? But surely the Chicken Man is sui generis.

Much like Robert Nifkin, Walter Galt never experiences a lone, singular transcendent moment, instead gradually easing into the secret Lower North Aufzoo world that was all around him all along. His mystical practice is Snarking. This operates more (again) on a level of metaphor than is usual in DMP, but surely Snarking is presented as a Mystery Cult with its own costume, sacred space, and nighttime sacrament. A movie theater is always an invocation of Plato’s cave. If Walter and Winston never quite manage to “rend the veil”—well, remember that Big Audrey, in a movie theater, does something quite like that, starting behind the screen and moving sideways out the exit door (#26). Maybe they’ll get there.

In my youth, Avocado of Death was my favorite DMP book, but one thing has slipped it down on the list. The text heavily implies that Walter’s parents, Theobald and Mildred, are in fact the same as detective Osgood Sigerson and his assistant Ormond Sacker. Sigerson and Sacker are themselves homages to Sherlock Holmes and Watson (Sigerson being a pseudonym Holmes canonically employs in “The Adventure of the Empty House” and Ormond Sacker ACD’s rough-draft name for John Watson) and it is clear that they have gone around having lots of fun adventures before the events of Avocado of Death.

But this means that Walter Galt, in escaping his deadly-boring existence, is only lamely following after his parents? How bunk is that! I didn’t realize the connection when I read the book as a child, and only later did the horrible truth come crashing down on me. I realize that the adventure was always in good fun and not exactly dangerous (except to realtors), but the presence of a family unit gleefully sharing the adventure together makes it sound more like a play-acting, a game without stakes (except to realtors). The book never really recovered in my estimation

I mean, it’s still one of the greatest books of all time, just not as high as it used to be.

•8 Bushman Lives! (2012 YA novel illustrated by Calef Brown)

[A gorilla-enthusiast (?) teenager in 1950s Chicago decides to study art and discovers a mysterious gorillacentric naval conspiracy.]

Bushman Lives is the capstone of DMP’s career. There would be other novels, and they have been fun, but none have striven so hard to be literature with a capital L. This is the story of Harold Knishke, an archetypal DMP protagonist and his conversion to art.

By this point in DMP’s oeuvre (this book came out in 2012), some things are, I think clear. Hogboro and Baconburg are just alternate universe representations of Chicago—Chicago is on the shores of Lake Michigan, while Hogboro is on the shores of Lake Michagoo; in Chicago, the Nor-Well Drug Company is on the corner of North and Wells in Old Town, while in Baconburg, the Nor-Bu Drug Company is on the corner of Nork and Budhi in Old Town; examples abound. That characters can travel through time, space, and the other, that they can be or meet multiple versions of themselves is well established in several previous texts, which explains how William Lloyd Floyd or the Chicken Man can exist, in different books, in both the real city of Chicago and the fantasy city of Hogboro.

Sometimes I think DMP established this framework simply so (in this book) Victor from Lizard Music could reappear in 1950s Chicago and seek simultaneously the island of the lizards and Bushman the Chicago gorilla (who may or may not be dead when the book starts but is nevertheless a major character).

I’m not sure if it’s possible to understand this book without having read a great many other DMP books (but especially Lizard Music (#1) and Adventures of a Cat-Whiskered Girl (#26), both of which it shares characters with). Perhaps it is impossible to understand this book fully regardless. How many secret gorillas are there here? You may expect a definitive answer, but you will not get one. Geets, at one point, disappears to join the navy, and you may think at first this is some sort of blunder on the part of the narration, a missing chapter establishing his departure—but then he leaves the navy and it turns out he didn’t even tell anyone he was going; he just went. The narration is true to the plot. And…Geets is a secret gorilla too? They’re everywhere! An entire school of exegesis should spring up around this book to plumb all its secrets.

As I’ll say again and again, the primary question in any DMP novel is how to express in words the mystical experience that DMP is always writing around or towards. Bushman Lives!, uniquely for DMP, answers that question like Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, by bringing Harold to the brink of revelation and then abruptly

ending. Perhaps I should be frustrated by this, but I think it is perfect. Every book DMP ever wrote is leading up to this moment, and here we are, trembling on the lip of the very thing they all, in different way, try to say.

As a special bonus, Bushman Lives! contains not only the most compelling and cogent analysis of schooling of any DMP book, but also the most compelling and cogent justification for art of any book anywhere: “Art does the least harm.”

•9 The Worms of Kukumlima (1981 middle-grade novel)

[Young Ronald Donald Almondotter, his grandfather, and a famous explorer travel to Africa to seek extraterrestrial (?) worms and their potential treasure.]

More than any other DMP book, Worms of Kukumlima is a straight-up adventure story in the H. Rider Haggard / Jules Verne / ripping yarn tradition. Following clues from the writings of a dead (?) man (as in She or Journey to the Center of the Earth) to find treasure in the heart of Africa (as in King Solomon’s Mines or Five Weeks in a Balloon) is as ripping as a yarn can get.

Of course this is a DMP book, so there are also giant worms and crunchy granola and a Nasser-faced pinball machine. The journey into the heart of Africa is never just a journey into the heart of Africa (thank you, Conrad), but in DMP’s hands it is a journey towards the mystical experience, an experience you only have when not looking for it. I’m not sure the experience ever actually arrives except in an allegorical representation: The Buddha-field is traditionally strewn with gems, much like Kukumlima, while setting the Buddha-field in a volcano is a powerful image I cannot quite unpack.

But it’s mostly adventure. No other DMP book is this exciting on a visceral (as opposed to intellectual) level. If I say this is a popcorn book, that is not a criticism. Nick Itch (Looking for Bobowicz (#100)) spends his childhood reading great adventure books in Classic Comics form and Neddie Wentworthstein (Neddiad (#15)) spends his childhood playing games based on the great adventure books the bigger kids have read—surely DMP cannot be grudged producing a great adventure book to rival these?

I once read a critical essay that claimed the guiding incident in adventure fiction set in Africa is a descent into a cave or other subterranean realm. Indeed, this happens in Haggard’s three most famous novels (KSM, She, AQ) as well as in Buchan’s Prester John and (of all books) Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King. Well, Kukumlima nicely turns the motif on its head as its heroes are stuck above ground, the villains, as worms, below.

But of course an adventure is always a journey far from the fields we know, and the adventure is only as good as the contrast with those fields. Narrator Ronald Donald Almondotter, like Victor in Lizard Music (#3), has little interest in hanging out through the boring summer, preferring to work at his grandfather’s salami-sealing company (the sausage industry is one of the primary employers in any DMP book), and the brief delineation of office life with the gin rummy and the classical music station and the National Geographics in the bathroom is both banal enough to want to leave and pleasant enough to want to return to.

Ronald Donald Almondotter also has the best name of any DMP narrator, and in Kukumlima the names just keep getting better: Seamus Finneganstein, Sir Charles Pelicanstein, and Milton X. Mohammedstein all show up in the first two chapters. (A question: Did Sir Charles Pelicanstein make the movie Eugene Winkelman watches about the quest for sea monsters in Lake Ontario, the one starring Ambrose McFwain (#37)? Evidence for yes: How could two such movies exist? Evidence for no: Would Sir Charles Pelicanstein permit anyone else, let alone Ambrose McFwain, to star in a movie he made?)

I’m not sure if the lengthy history of the London Earthworm Society is the first of DMP’s shaggy-dog segues that go nowhere, but it’s certainly an excellent one (Borgel’s tale of his boyhood in the Old Country is probably the best, unless one counts the entirety of Young Adult Novel (#2)).

If I’ve failed to make Kukumlima sound as profound as some of DMP’s other books, it is nevertheless twice as fun. And surely there is some mystical secret to be drawn from the mystical quest for Kukumlima, the peace that passes understanding, the flight to freedom, the bombinating worms…

•10 Wingman (1975 middle-grade novella)

[While avoiding his cruddy racist school, Donald Chen encounters a flying superhero.]

Wingman is an outlier in DMP’s canon. It is his most serious book. It is his least Jewish book. It may be his first book of any real length (Blue Moose (#59) came out the same year, but it’s shorter anyway and I don’t know which one was first). And yet in some ways it fits right in: It is the story of an alienated young man who hates school and likes comic books (he has, in fact, the greatest comic book collection of any DMP character, and that includes such luminaries as Alan Mendelsohn (#1), Steve Nickelson (#58), and Nick Itch’s father (#100)). Most importantly, its protagonist is the first, but far from the last, in the DMP canon to have a mystical experience through the agency of art. Long before Harold Knishke enters de Kooning’s Excavation (#8), long before DMP (in Fish Whistle (#6)) tells the autobiographical story of himself entering into de Kooning’s Excavation, Donald Chen enters the Chinese artwork at the Met. The mystic visions Donald experiences (on more than one occasion) are among the most overtly mystical of any experience of any DMP character (I put them at fifth, after those in Java Jack (#19), Borgel (#11), The Neddiad (#15), and Adventures of a Cat-Whiskered Girl (#26) maybe?).

Perhaps because it is racially motivated, perhaps because it is not flecked with hyperbolic humorous touches, and perhaps because it takes place in a very real contemporary New York City and neither a mythic city like Hogboro nor a real city in the romanticized past, Donald’s alienation is hard to bear. Perhaps the only joke in the book is the suggestion that Superman (in one of Donald’s comics) might have to seal the Hoboken Dam before it sunders, sweeping Hoboken away—and even that is only funny if you’ve lived in or near Hoboken. When I read the book as a kid I dismissed it as self-serious, a minor work.

But I came to love it later in life. DMP knows what he’s doing, and the serious world of Donald Chen’s Washington Heights exists in contrast to the strange and unsettling appearances of the titular Wingman. The burgeoning wackiness of DMP’s usual settings can run the risk, like García Márquez’s Macondo, of drowning in quirkiness. Of all DMP works longer than a picture book, only Wingman truly partakes of what Tzvetan Todorov would call “the fantastic.”

It is, DMP claims, “mostly a true story.”

•11 Borgel (1990 middle-grade novel)

[Melvin Spellbound and his distant uncle are tourists, traveling through a surreal version of outer space (as well as time and the other).]

Borgel is a time bomb of a book. I doubt of anyone, in 1990 when the book came out, expected it to present a kind of roadmap for the overarching DMP universe. Thematically, and quite explicitly in the text, the map it resembles is a map of New Jersey. I guess technically the idea of different existential planes arises in Alan Mendelsohn (#1), but Borgel set the tone. Tone is the most important part of any book. The tone of Borgel is anything goes!

The basicest plot should be familiar. I mean, it is [pastes]: An alienated young man meets a weird character, gets drawn by him into an ever-weirdening world of weirdness, and finally achieves some kind of transcendent experience. The weird character is a distantly related Uncle Borgel, who displays at least a surface resemblance to the Uncle Boris who appears in every DMP memoir (and also Alan Mendelsohn). But Borgel’s weirdness surpasses Boris’s, or almost anyone’s, and soon he is taking our narrator, young Melvin Spellbound, on a journey through time, space, and the other. I think there’s a tendency, in discussing Borgel, to focus on the time travel aspect—Borgel’s fantasies about being immortalized in a TV special all involve time travel in the title, and the book was published in the UK under the title The Time Tourist—but since he never visits ancient Rome or anywhen identifiable, the feel of the book is more like he’s traveling through space. But probably we were wrong to focus on time and space in the first place. Probably we should be focusing on the other.

All of DMP’s books are about the other—not the way all Lovecraft books are, not that kind of other. “The other” is the third thing, the tertium quid, that gets defined no other way. It’s not A or ~A. It’s not sleeping or waking. It’s not Bing or Frank. You don’t know what it is, but you know what it isn’t. The heart of every DMP novel, remember, is the inexpressible transcendent thing. It’s the thing I mean. The noumenal; the Lacanian Real; “where your eyes don’t go.” Whatever it is, it’s the thing we’re talking about, the thing no one can talk about.

And, yeah, that’s what this book is about. There’s a lot of fun stuff, and Borgel’s fables4 are among DMP’s best work, but the real meat of the book is the story of the quest for the Great Popsicle. The Great Popsicle is not actually the other (in the time, space, and the other trichotomy), but it is the other (in the sense of the thing we’re talking about). The Great Popsicle is some kind of manifestation of the divine. Its appearance as a benevolent romping popsicle is one of my favorite passages in DMP (and therefore all of literature). And then (I’m assuming you’ve read the book) it gets eaten. All goodness and joy in the universe, devoured by a Grivnizoid. Whereupon the Grivnizoid becomes all goodness and joy in the universe. This is the moment. All of DMP’s work turns on this axis.

Not for a while, though. DMP’s next book, The Afterlife Diet (#18), only resembles Borgel in the crazy interpolated summary-within-a-novel “The Diskountikon” (which resembles Borgel an awful lot). His follow up, Robert Nifkin (#4), has a hero who absolutely does not travel through time or the other, and very little in space and not at all in that kind of space (California → Chicago → Annandale-on-Hudson is all, and that off-page). It’s only in 2007’s Neddiad (#15) that the basic worldview of Borgel—universal benignity, that is—returns, and only in Neddiad’s sequels that the shape of the DMP universe becomes clear.

Just as all Milo Levi-Nathan’s craziest book proposals in The Afterlife Diet prove to be, in some sense, true, the craziest DMP books that you assumed were deuterocanonical prove to be perfectly plausible. Guys from Space (#17) and Ned Feldman (Space Pirate) (#25) and Mush (a Dog from Space) (#72) are all, it turns out, not only perfectly plausible but not even far-fetched. I mean Borgel could as easily play jazz with Mush as he could raid Spiegelians with Bugbeard as he could drink root beer with the space guys as he could do anything. After Borgel, anything goes. That’s the true legacy of Borgel. Eventually (after The Neddiad, as we shall see) anything went!

This book is so good that I keep thinking I ranked it too low, but then I look above and all the books that beat it are so good, so what is one to do? It’s all part of the cutthroat zero-sum-game of substack.

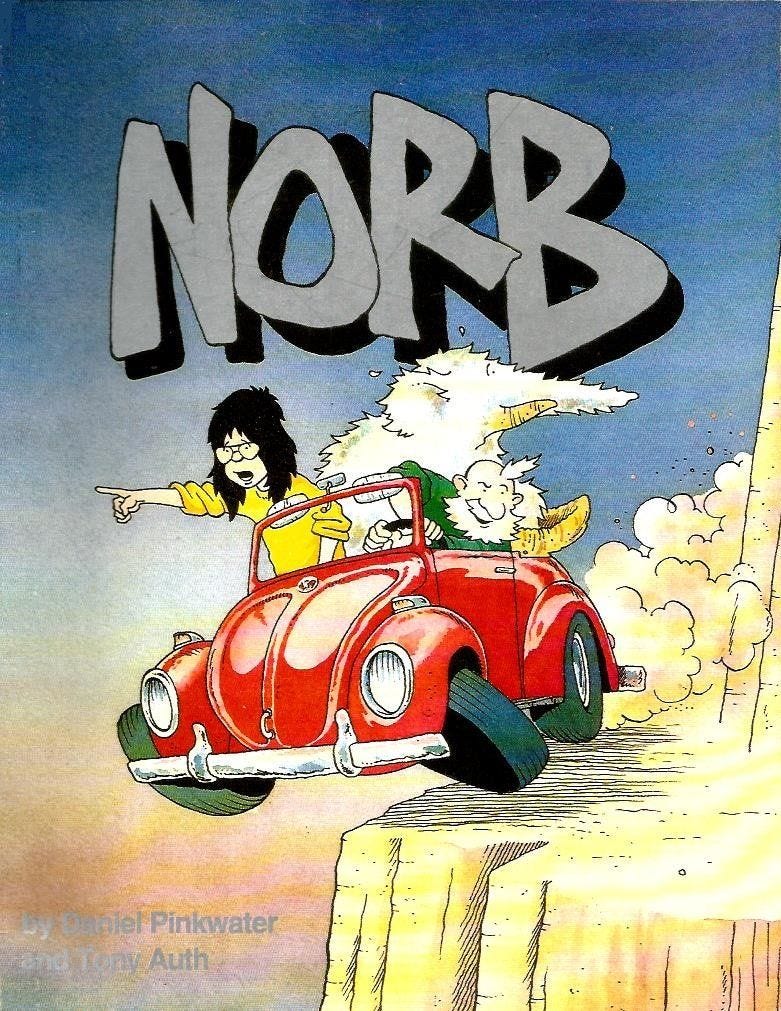

•12 Norb (1992 comic strip collection illustrated by Tony Auth)

[An eccentric inventor and a neighboring teenage girl have various strange adventures, one installment a day in your local newspaper.]

For one brief, glorious year, DMP had a syndicated comic strip (illustrated by political cartoonist Tony Auth). That “year”—it ran for 362 days between 1989 and 1990—was a good time for comic strips: Bloom County was wrapping up and FoxTrot was starting; Calvin and Hobbes had hit its stride, Far Side was still going strong, Robotman was getting better and better, Dilbert was not yet crazed, and Peanuts was entering a kind of late-in-life elder-statesman renaissance. There was a lot going on.

But the DMP/Auth strip took its cue from none of these. Norb looks back to the humorous adventure/continuity strips of yore: Thimble Theatre, Li’l Abner, and especially Alley Oop (a caveman named Oopy Al accompanies our heroes on one of their time-traveling junkets, a detail perhaps too on point). Over the yearlong run, Norb (an “eccentric genius,” his name short for Norbu, which is both a Himalayan peak and (Nor-Bu, remember?) a drugstore in Baconburg) and his neighbor Rat (Bentley Saunders Harrison Matthews, the tritagonist from the Snarkout Boys (#7 & 30), somewhat defanged) have a wide variety of variegated adventures, sometimes solving crimes, sometimes just dealing with an annoying houseguest. The whiplash effect of these storylines is like…well, there used to be a weekly comic strip called Sappo.5 For six Sundays in 1937, Sappo’s wife has been trying to catch him sneaking out to play poker. Then come five Sundays in which Sappo switches brains with a dog. There follow three Sundays of slapstick gags at home. Then for six months Sappo travels through space (with his wife and friends). After they get back, there’s a month about competitive duck hunting. Well, Norb is like that.

What you get is, on the one hand, exactly what you might expect a DMP adventure strip to be like (weird and funny). On the other hand, it is unlike any other DMP text. The characters are aware they are in a comic strip, frequently remarking on the conventions of the form in a Sam’s Strip kind of way. One mystery requires a trip to a soiree populated entirely by old comic characters: “Wow! Look at all those old fogeys!” Rat exclaims as he looks across a room that includes, inter alia, Wimpy from Thimble Theatre, Mammy Yokum from Li’l Abner, and Alley Oop himself. For the next two weeks, the fogeys trade Attila the Pun-style one-liners as Rat groans.

(Note that the presence of Rat seems to indicate that in some sense, at least, the strip takes place “in continuity,” which can cause some complications. Rat’s ever-absent parents attend (at one point) a “sensitivity seminar” in Peru; Peru is of course where their nemesis/erstwhile butler Wallace Nussbaum hails from! Is something going on behind the scenes?)

The project was doomed from the start. America’s expectations from comic strips by 1990 had become: things you cut out of newspapers and magnet to a fridge. For all the exciting appearances of innovation alluded to in the first paragraph above, the comics page was still safe and cozy, rarely “challenging” (you know what I mean), and primarily composed of titles that started decades earlier (as is still the case). In 1990, The Katzenjammer Kids was still in syndication!

But worse than audience prejudice was the pure physical restriction of the medium. Adventure strips need art! This is true of “straight” adventure strips (Caniff, Raymond) and also of the humorous ones Norb takes as its model, but by 1990 comics had shrunk too greatly to allow much art in them. A daily installment of Alley Oop or Li’l Abner regularly unspooled across four big panels (Thimble Theatre averaged six!), but Norb is almost always restricted to three cramped panels. When Auth tries something ambitious, like the distorted forms of our characters as they rocket through time, you can really perceive how limited he is, trying to cram the information into a tiny box. Bill Watterson was the last great strip artist (even if not necessarily the last great strip cartoonist) because he kept his virtuoso art moments for the Sunday pages, where he had space, and if you have a rival in mind (John Cullen Murphy, maybe?) it’s probably on a Sunday strip. Of course, Watterson spent his whole career railing against what shrinking comics strips were doing to the art.

So Norb lasted only a year, was largely hated or ignored, and suffered the ignominy of a neglected afterlife. The Sunday have never been reprinted. The dailies have been collected in their entirety only once, in an impossible-to-find 19926 volume from Mu Press with what may literally be the worst binding of any book ever made.

The name Mu evokes, lost continents, Zen nothingness, and the coefficient of friction; as you search for a copy Norb (as you should), you will see how all three apply. Those who believe in comic strips as an art form (like me!) should make the effort.

•13 Ducks! (1984 picture book)

[Scott purchases a duck who bullies him into wishing for a chariot that carries him to heaven, or maybe duck heaven. Ducks lie.]

Some of DMP’s picture books are more tone-poems than anything else, but Ducks! tells a story, and it is an insane story. It’s more or less the old tale of the fisherman who saves a talking fish, only in this case the fish is a vaguely hostile duck who is also (everyone agrees) a serial liar. Scott, our young narrator, is taken up to heaven in a chariot—this appears to be an Elijah reference, and presumably the chariot is only not fiery because DMP testifies (in Young Adults (#2)) that he can never spell the word fiery correctly—and then returned home after being jerked around a bit.

All of this makes some sense when viewed in the light of other DMP books. Scott has a mystical experience, in fact the mystical experience as he ascends Elijah-like to heaven, but the experience is kind of lame and boring (you know, like Waka Waka (#1)). The unnamed duck is similar to other bossy DMP guides or interlopers. Scott joins Donald Chen (#10), Seymour Semolina (#20), and Ned Feldman (#25) as characters who get a feathery ride. Ducks are the “major enthusiasm” of Colonel Ken Krenwinkle’s life (in Yobgorgle (#37)).

But what if you’re reading Ducks! in isolation (as presumably many young readers would be)? What should anyone make of this story? It’s merely an account of how Scott loses seven cents!

Of course, that’s why I love this book. It’s an unstory. The parents keep coming in and summarizing everything that happened in painful but hilarious expository dialog. “Mothers and fathers usually lie,” the duck says, but ducks usually lie.

Ducks! may not be the weirdest children’s book ever made—because ECK used to put out children’s books—and it may not even be the weirdest great children’s book (because Maurice Sendak’s Outside Over There), but it’s too weird even to be a tone poem. I don’t know what it is. It is, of course, (as another kind of Duck would say) a Dada story.

Perhaps it’s worth noting that Reverend Nathan DuNord, in his insane screed Modern Art, An Invention of the Devil, suggests that pictures of ducks are the only valid form of art. This screed, of course, comes from Bushman Lives! (#8), the only other DMP book to end in a !7

•14 Wizard Crystal (1973 picture book)

[In search of happiness, a wizard steals a magic crystal from a frog pond.]

It’s hard to compare a novel with a very short text that contains only a few hundred words or so, but, hey, this is the task we decided upon. I am aware that I favor the longer works (certainly they’re easier to write about), and perhaps I’ve tried to be fair and fight my prejudices by giving the picture books bonus points. You’ll never know.

But Wizard Crystal is the real deal. I found this book terrifying to read as a youth—and I mean as a teenager; I didn’t read it till I was a teenager. It’s a theme DMP would return to in later books, but here presented in a way that is strange and unsettling. It’s more or less Borgel from the point of view of the Grivnizoid, if that makes any sense. It’s an unpleasant experience. It’s a great book. Even the font is horrible.

The calif seeks the subterranean palace of wonders and learns too late it is hell—this is the plot of Beckford’s eighteenth-century gothic novel Vathek, but it is also the plot of Wizard Crystal…with the curious coda that maybe everything is in fact all right. Maybe it’s nice here in the subterranean palace of wonders.

This book also contains my favorite DMP art—not my favorite art in a DMP book necessarily, but my favorite art by DMP—especially the wizard’s hat.

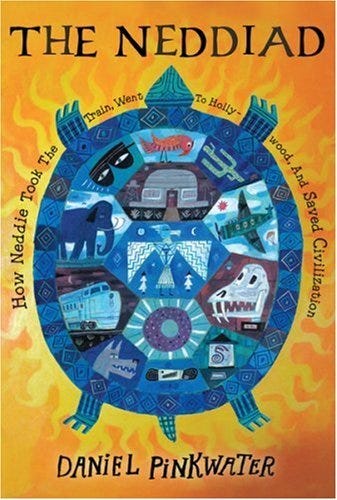

•15 The Neddiad: How Neddie Took the Train, Went to Hollywood, and Saved Civilization (2007 middle-grade novel illustrated by Calef Brown)

[Neddie takes the train, goes to Hollywood, and saves civilization (from the return of antediluvian chaos).]

I don’t know what marketing exec decided to make the push, but Neddiad was a big deal when it came out. The whole thing was serialized online. There were contests (I won one, and the Calef Brown art from chapter seven still hangs upon my wall). It seemed like everyone was talking about the book. The last few DMP books had slipped out quietly, but this one made a splash. It was at the time, and remains, the longest DMP book (excluding omnibuses, of course). It’s a big one. There’s a lot going on!

The Neddiad is an inflection point in the canon of DMP novels. After this one, and perhaps starting with this one, everything would feel different (except Bushman Lives!). There are a lot more prophesies, and a lot more witches. There are a lot more female narrators. Where previous novels had skewed urban, after Neddiad the novels would skew rural, with even the ostensibly urban environments (Poughkeepsie, Kingston) frequently abandoned for the wilds of the Catskills. Essentially, Leonard Neeble and Alan Mendelsohn (#1) may live in the suburbs, but they pine for the Old Neighborhood / the Bronx and only find salvation by taking a bus into Hogboro; their idea of wilderness is an overgrown tourist trap next to a junkyard. Post-Neddiad characters (contrarily) head for the forest primeval at the drop of a hat, either on this plane or another. (Bushman Lives! (#8) is more or less an exception, but you’ll notice Geets Hildebrand and a host of ape-men have one eye on the woods…someone has to put the wald in Waldteufel…etc.)

But a lot of that is post-Neddie. Neddiad is both the last of the old-style novels (not literally the last—there’s Bushman Lives!) and the harbinger of the new style. For all its evocation of The Illiad (perhaps more obvious after The Yggyssey was released), The Neddiad is structured more like The Aeneid: First Neddie Wentworthstein makes his long and perilous journey from Chicago for California, and only then does he have to fight for it.

The stakes are bigger than in previous DMP books—actually the stakes in both Lizard Music (#3) and Avocado of Death (#7) are huge, involving as they do aliens taking over part of the earth, but of course in those books the aliens win—and Neddie has to save, as the title says, civilization. In the course of said saving, he undergoes a mystical experience that is one of the most overt mystical experiences in the entire DMP canon. The revelation of the Great Popsicle is echoed quite precisely in the revelation of the Great Turtle. Even if you think I’m usually talking out of my hat about the mysticism, you really cannot deny this one!

All of this is all good stuff. But I want to talk about another thing the book does, something that doesn’t quite start with The Neddiad but which gets properly launched with The Neddiad.

I quoted before DMP’s statement on his purpose in life: “to tell people who might not have seen it that such a place as the Clark existed” (#6). More than ever before, The Neddiad is about the past, and DMP’s memories of the past, and the preservation in memory of a time and place that has long faded away. This is the Los Angeles of ca. 1950, with its stucco and its kitschy buildings in various shapes. The Hollywood Ranch Market was a real place and the brown Derby was a real place and Clifton’s Cafeteria (they go there in The Yggyssey (#81)) was a real place, and DMP through the magic of art is going to recreate them all as they were in their heyday. The Monte Vista Hotel is still a real place (in Flagstaff, Arizona). Pollepel Island in Cat Whiskered Girl (#26) and the Kingston Stockade District in Dwergish Girl (#31)…there’s a real sense that DMP is sharing something almost forgotten with you, the reader. I never rode it, but such a train as the Superchief used to roar across the West.

DMP has always excelled in creating a rich and vibrant (I should fix that cliché) setting, and the gurus and health food joints and new age bookstores of 1970s DMP preserve (as any author preserves; only he’s better at it) the moment the books were written in. But starting with Robert Nifkin (#4), set in the Chicago of the past, the impetus to keep safe a moment long gone, like Uncle Boris filming a forgotten Oriental Garden (#1), starts to emerge.

There have been infodumps in DMP books before, and one remembers Theobald Galt’s lecture on werewolf etymologies in Baconburg Horror (#30). But nothing, not even Robert Nifkin’s reports on Chicago architecture, could prepare one for the information in The Neddiad. It is far-ranging, with prehistoric epochs and Native Americans and did you know the alligator snapping turtle is the largest freshwater turtle in North America? But mostly it’s about Hollywood. Pace Sir Charles Pelicanstein (from Kukumlima (#9)), but Los Angeles exists after all.

These infodumps are presented with a twinkle of irony, and I’m not complaining about them. They are at least in part a parody of worse books with more irritating infodumps, or even of infodumpy Moby Dick (and see Magic Goose (#20) below for the ad absurdum end of the parody). But there’s no avoiding their presence. If DMP books are a map for the young reader to escape a rotten life, they are sometimes a very specific map for a very specific time, when a hip youngster could avoid the mundanity of conventional media by indulging in Lord Buckley and listening to “Serutan Yob” and perusing a pseudo-poem at the E.J. Sperry Thought Factory. The fringe or underground aspects of these specific media shade through the “cult” texts of B-movies or old comics books or Mississippi John Hurt’s “Chicken” (which is not like his other songs) and Screaming Jay Hawkins’s “I Put a Spell on You” (which is indeed like his other songs) and into the conventionally immortal art of Mozart or even Louis Armstrong (these are not my but DMP’s examples). The hi/lo of the Cl/Sn/ark Theater, which you can imagine might show Glen or Glenda? on a double bill with Grand Illusion (part of their alphabetical series; this one is my example) is the ultimate avatar of the DMP esthetic.

This is the civilization Neddie has been fighting for, and if it is forgotten, Neddie will have failed.

•16 Author’s Day (1993 picture book)

[An almost-recognizable author comes to a local grammar school for author’s day.]

Fish Whistle (#6) contains an essay about a young man possessed of “a large collection of light reading—authors like Kingsley Amis, S.J. Perelman, and Jerome K. Jerome.” Well, Author’s Day is the Jerome K. Jerome of DMP books. It’s light, but it’s funny enough to be a classic.

Bramwell Wink-Porter, a writer who bears a passing resemblance to DMP, visits Melvinville Elementary School, and farcical disasters spiral out of this slim premise. The children are straight out of “Ransom of Red Chief.” The adults are crazy. It’s a good time.

I should note that one speaker from the Blueberry Park / Bughouse Square section of Snarkout Boys and the Avocado of Death (#7), the one who wants animals to wear clothing, is revealed to be Melvinville teacher Mrs. Heatseat—but such knowledge is hardly necessary to enjoy the book.

In 1993, when Author’s Day came out, the idea that DMP would write a book (as Bramwell Wink-Porter did) called The Bunny Brothers must have seemed as absurd as a petition for animals to wear clothing. Things would change…

•17 Guys from Space (1989 picture book)

[Space guys take a young boy on a journey into space in search of adventure and root beer.]

Almost all of Guys from Space is written in very short sentences, each sentence being an entire paragraph. I realize that is is less a stylistic idiosyncrasy than a nod to the fact that this book is aimed at very young children, but actually very few DMP books are written in this way. I am aware that other writers have tried the one-short-sentence-per-paragraph style out and come across looking like illiterate savages, but here it gives the book the cadence of a poem.

It did not make a noise.

It landed like a dream.

“This is good!” I said.

I was not scared.

This is, I think, the first of DMP’s dialog-heavy picture books (although some might point to The Muffin Fiend (#23) for priority). As in an Ivy Compton-Burnett novel, most of the action comes through dialog, and this, too, gives the book a slow, dreamlike rhythm. It takes a full page for the space guys to convince our unnamed narrator to get permission to go on their spaceship!

The actual voyage of adventure and exploration is utterly charming in a childlike way. The trip takes them to an interplanetary root beer stand reminiscent of the one run by Alfred the anthropoid bloboform in Borgel (#11) (or the one run by Sid the amorphoid fleshopod in Afterlife Diet (#18)). They get a genuine discovery (ice cream in root beer—a pleasantly DMP discovery in that it is retro and also involves junkfood) and arrive home in time for dinner.

Guys from Space is in many ways a sister book to Ned Feldman, Space Pirate (#25): Both take a small boy through space to a distant planet, both involve the plan of testing alien atmosphere by stepping out into it (and running back to the ship, slamming the door, should it prove unbreathable), and both involve a big yellow smiley face (it’s being woven on a loom in Guys from Space). But while Ned Feldman is a cynical comedy (and an excellent one), Guys from Space is the most innocent of the great DMP books. “We are space guys. We know what we are doing.”

•18 The Afterlife Diet (1995 novel)

[The afterlife turns out to be segregated by weight; author and editor engage in a savage duel to the death, as nature says they must; meanwhile shadowy forces from the old world, many of them fat, strike out into in the new.]

DMP must have been aware that he would have only one chance to produce a novel for grown-ups, so he crammed everything in here: fat people, aliens, vampires, werecreatures, cults, fat people, Moby Dick, sausages, Eastern-European Jews, parakeets, and more fat people. Like many DMP novels (post-Slaves of Spiegel (#48)), it is a palimpsest constructed from several stories in several timelines………plus a madman’s notebook (which the novel resembles), more than one book proposal (some of which, in the context of the novel, prove to be nonfiction), and ever so many digressions. Part of it takes place in the afterlife, which resembles a lame Catskills resort. There’s plenty of sex, most of it not so much graphic as…sausagey. Almost every character is fat.

It’s tempting to skim the interpolated texts here, but one lengthy part, “The Diskountikon,” may be the single best thing in The Afterlife Diet. “The Diskountikon” is itself a kind of travesty of the Melvinge of the Megaverse trilogy—books DMP oversaw in some nebulous way but did not write. Instead of Melvinge, the main character is Irvinge. Instead of an enormous unobtainable mall, the characters seek an enormous unobtainable discount pharmacy. The idea of a store so large that its parking lot swells to impossible sizes—it takes three or four generations to make a trip to the mall, “the first of which is spent looking for a parking space”; subsidiary shops pop up in the parking lot, and you’re never sure if you have reached the actual enormous store or just one of these ersatz distractions—is one of the best in all literature, and it’s nice that DMP salvaged it from the Melvinge books to establish it in one of his own.

The book is perhaps overly didactic—its theme is that fat people should just mellow out and be fat without worrying, and you will not miss that theme—but it’s funny enough that the sting of didacticism gets absorbed. The one fat character comfortable with his weight is a skydiving carpe-diem maniac who lives quite literally in a perpetual orgy—there’s a moral here, but it’s mostly just silliness.

Perhaps not all of it works, but the book is so audacious and ambitious that with every rereading it gains in my estimation. It also contains the first appearance of Robert Nifkin’s Wheaton School (#4), about two-thirds of Vampires of Blinsh (#28), a very different Gypsy Bill from the one that appears in Borgel (#11), and a cameo by fan-favorite Rolzup.

•19 Java Jack (1980 middle-grade novel by Luqman Keele and DMP)

[The putative child of anthropologists travels to Indonesia after reports surface that his parents are dead; there he becomes a pirate, prophet, and rock musician before things get weird.]

Worms of Kukumlima (#9) is DMP’s semiparody of a boy’s adventure story, but Java Jack is straight up adventure, no parody. It’s a little bit Lord Jim, with a touch of She, but the book it most resembles is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped: the first-person account of a boy out of his element becoming entangled in local politics; Bunga is Alan Breck.

Actually, the book it most resembles is Worms of Kukumlima, down to the gem-strewn Buddha field in a volcano. But, as I said, it’s played much straighter. Instead of Milton X. Mohammedstein, there are real Muslims.

Java Jack the book is attributed to Luqman Keele and DMP, in that order, and I have no idea how the collaboration went down, but the prose reads like DMP, the plot is (almost) classic DMP, even some of the smallest touches (Raymond!) are pure DMP. The local color of Indonesia is Luqman Keele, of course—he seems to have lived there much of his life—and I don’t mean to downplay his contribution. Ever modest, DMP has asserted that he was more of an editor, that the book was really Keele’s. What do I know? I’d say DMP’s fingerprints are all over this thing. And the end of the book—here is where Luqman Keele and DMP may share sensibilities.

Luqman Keele (also known, confusingly and later in life, as Luqman McKingley) seems to have been active in something called Subud. I know a Wikipedia amount about Subud, but basically it’s an Indonesian-based spiritual movement. Keele wrote a biography of (and edited a series of transcripts from talks by) Subud’s founder. Based on the fact that the biography is entitled Journey Beyond the Stars, I’m assuming there’s a lot of Subud in Java Jack. The Subud symbol is seven concentric circles, and the entrance to the Fiery Star is “on a island [1] inside a palace [2] that was an island in a pond [3] on an island [4] that was in a lake [5] inside a volcano [6]—which was on an island [7].” Subud syncretically adopts influences from several faiths, and the Sultan of Maggasang’s opening of the treasure house requires the cooperation of five holy men, “one representing each of the major religious communities of Maggasang.” How much Java Jack’s journey “outside the material universe” represents authentic Subud cosmology or teaching—probably someone should read some of Keele’s other books and report back. That someone might eventually be me, but I haven’t done it yet.

The Subud ritual of latihan is referenced by a DMP character some thirty years after Java Jack, in 2010’s Adventures of a Cat-Whiskered Girl (#26), but never in Java Jack itself. Regardless, let us note the presence of a mystical experience at the climax of a DMP book. And what a mystical experience it is! All the haters and doubters who are sniffing that the Snarkout Boys never really achieve transcendence have nothing to object to here! This is not my favorite mystical experience that a DMP narrator undergoes, probably because it is far from the clearest, and that may be because more Subud knowledge is required to get all the details—but it’s got to be the most mystical!

Luqman Keele died (under the name McKingley) in 2012. You can find a brief obituary here.

This is probably the most violent DMP book (Afterlife Diet (#18) excepted), but it is also the one that most embraces repentance and forgiveness. Fligh is the single most evil character in any DMP book, Nussbaums included, and he is well on his way, at book’s end, to joining Doctors without Borders. The pirate becomes a benign capitalist. Java Jack is off on more adventures!

I hope my habitual carping does not obscure the fact that this is a real rip-snorter of an action book, apparently but unjustly neglected by DMP fans. Also, the fictional island of Maggasang, where the climax of Java Jack takes place, is, we learn in Avocado of Death (#7), where “the best orangutans for wrestling purposes come from.”

(There exists an unrelated (?) 1927 novel called Java-Jack, which I have never read but probably should unless you beat me to it.)

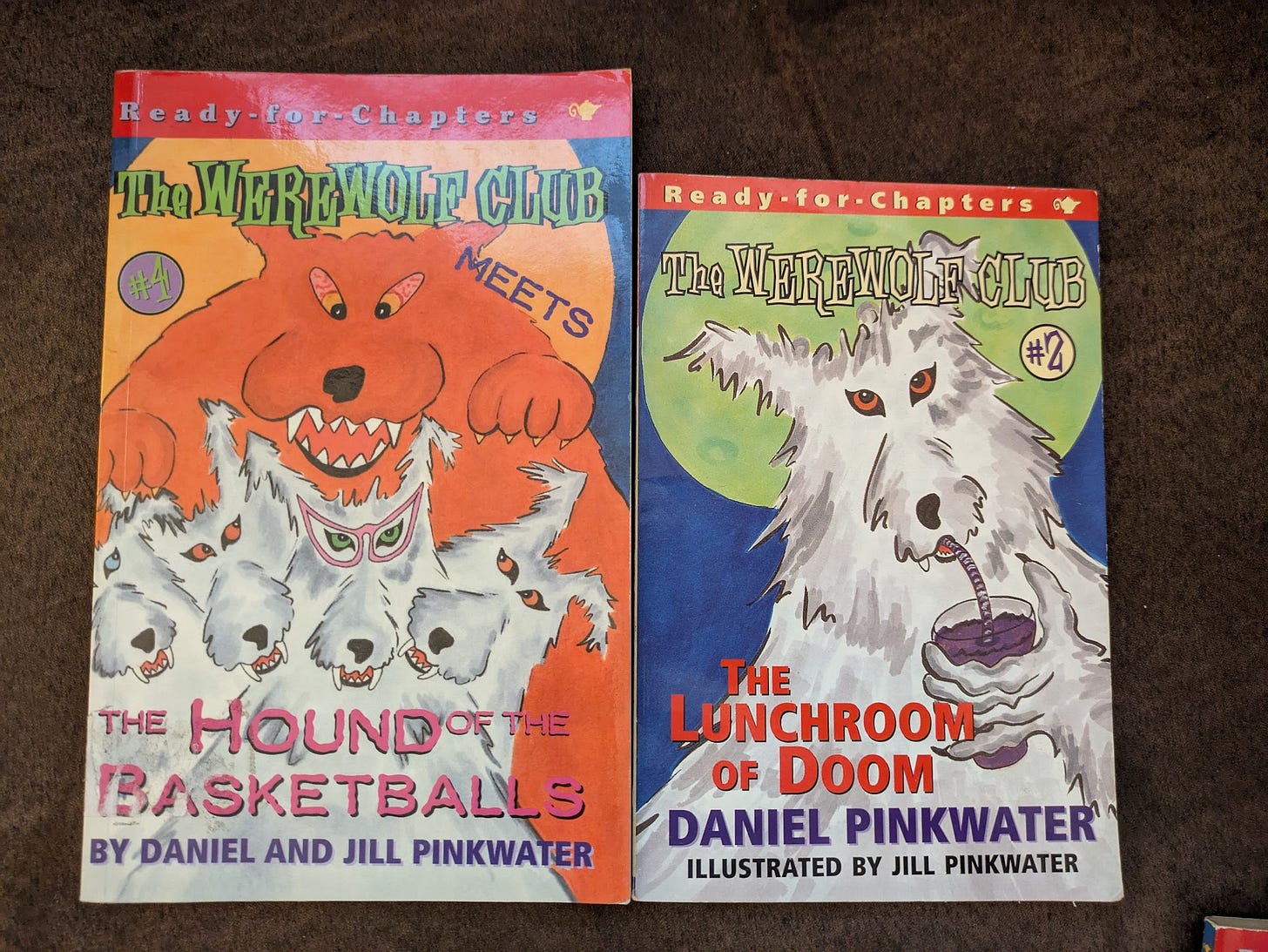

•20 The Magic Goose (1997 children’s book illustrated by Jill Pinkwater)

[A giant talking goose flies a kid around at night so he can visit an author (and also, you know, just fly).]

The Magic Goose is, more than most DMP books, pure parody. A kid (Seymour Semolina) has absorbed from children’s literature an idea about what a visit from a magical creature should be like. One day a magic goose visits him, and the goose is just terrible at his job. The entire book is the goose failing to take Seymour on an adventure while Seymour badgers the poor fowl. Maybe I would have found this frustrating if I were still Seymour’s age, but I’m not so I find it hilarious.

DMP characters frequently speak in ridiculously thorough infodumps, providing lengthy discourses on the history of werewolves, coracles, drive-ins, or especially art. These infodumps are, I think, also parody, the kind of thing a character in a bad thriller would do, but made ridiculous with the amount of (for example) etymological detail provided. Well Magic Goose is hardly the most infodumpy DMP book (that would be one of the Neddiad trilogy (#15, 81, or 26)), but it manages the nice work of self-parody, providing periodic vocabulary definitions that are straight up extracted from the dictionary.

Apparently this was originally released under the title Goose Night, which is better, but I read the (more common) Magic Goose edition and am congenitally inflexible.

•21 Tooth-Gnasher Superflash (1981 picture book)

[A family goes shopping for a new car.]

In some ways Tooth-Gnasher Superflash is just a joke, with a punchline and everything. It’s a good joke, but a joke is hardly going to rate a book this high on the list. What I love about Superflash (and as always I may be reading too much into things) is the deadpan absurdity of the characters’ speech, which suggests nothing so much as a Ionesco play. If you like the Bald Soprano or The Lesson (which also has a punchline) you’ll love Tooth-Gnasher Superflash. That’s all I have to say about that.

•22 Wempires (1991 picture book)

[A vampire-obsessed kid gets visited by real vampires.]

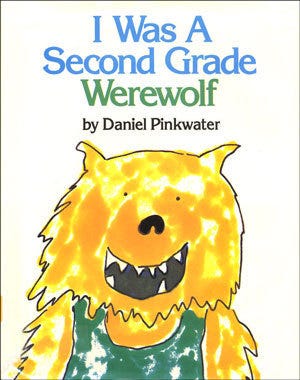

This book starts out as just another picture book about children interacting with classic Universal Monsters (you know, like I Was a Second-Grade Werewolf (#55)). But then the Wempires show up—and these guys are great! Their Borscht-belt accents and boorish behavior as they plunder Jonathan’s house for snacks—this is true comedy.

“Drinking blood—yich! Now for drinking, ginger ale is the best” is the single DMP line that gets quoted the most in my house.

•23 The Muffin Fiend (1986 children’s book)

[Mozart helps solve the crime of the missing muffins. It was aliens all along.]

Young Adults (the complete version, not the bowdlerized massmarket reissue; #2) contains absurd low-res illustrated tales of the superheroics of Wolfgang Amadeaus Mozart. Muffin Fiend could be a stylistically identical and tonally similar outtake of the Young Adults Mozart stories.

In Muffin Fiend, Mozart is now a master detective, prone, much like master detective Osgood Sigerson in the Snarkout Boys books (#7 & 30) to say things like, “I used to know but I forgot.” He is visited by Inspector Charles le Chat (which of course means Charles the Cat—Young Adults readers take note!) and contracted to find who’s been stealing the muffins of Europe. In a plot twist that will be repeated in Borgel, the fatal clue comes from the fact that someone elects to eat inedible food.

Mozart claims to hold the record for the greatest number of muffins consumed in twenty-four hours, which happens to match the number of conquests Don Giovanni (in the Mozart opera of the same name) claims in Spain: 1003.8 When Mozart has a showdown with the muffin fiend, however, it is the fiend who has taken the Don Giovanni role, and Mozart is the statue: In their duet, the fiend sings “No!” again and again and Mozart offers a fatal handshake.9

As one might expect from a book that is practically a spin-off of DMP’s most Dada book, the ending is “a Dada story.”It’s also remarkably similar to the endings of Fat Men from Space (#51) and Avocado of Death (#7), which is quite a feat because those endings are not similar to each other.

Despite its surface occult apparatus (that stray illuminati pyramid) and operatic intertextuality, this scherzo has little depth I can tease out beyond its inherent absurdity. But that absurdity is sufficient to make this one of DMP’s most fun divertimenti.

I’m not sure if anyone noticed, but I worked some music terms into that last paragraph.

•24 Devil in the Drain (1983 picture book)

[A boy discovers the devil lives in his kitchen sink and is also a jerk.]

DMP’s picture books often (Wempires (#22), Magic Goose (#20), Ned Feldman (#25), etc.) involve a kind of home invasion, and the invader is generally a bossy, selfish jerk. The Wempires are charming, but they’re also here to make a mess and clean out Jonathan’s kitchen. The Magic Goose may have good intentions, but he in such denial of his own incompetence. Captain Bugbeard’s only redeeming feature is that he knows how to fly a space ship, and that only most of the time. I’d put the hostile duck from Ducks! (#13) in this category, too; but at least he gives you a chariot with a nice paint job. Even he has an upside.

But then there’s Devil in the Drain, which is about an invasion by the actual Devil. Like Captain Bugbeard, he comes through the sink. Like many DMP characters, he’s here to demand food (and like Lance Von Sweeney (Magic Pretzel (#53)) or Glamorella Katz (Kat Hats (#42)), he is obsessed with pretzels). And he’s just rotten. He’s awful. He’s literally the devil!

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this book (ever since I first read it, reformatted as a short story, in Marvin Kaye’s SF anthology Devils and Demons). Does the unnamed narrator damn himself by breaking his word to the Devil (and was this, in fact, the Devil’s plan?)? Or (and this seems more in keeping with DMP’s usual worldview) is the whole point of the story that the Devil is there to make you worry about things you should’t worry about (such as accidentally draining a goldfish), and the only thing to do is flush him away out of your thoughts?

Of course, the fact that the Devil resemble the dead goldfish—is he the ghost of the goldfish out for revenge? Or is this encounter taking place inside the narrator’s conscience, where he has conjured up a dead goldfish to hound him, Furies-style?

If this book were a moral fable, I’d say it was a failure, being too unclear, but the book is art, and art should make you think.

“How come you haven’t mentioned how frightening I am, and at the same time sort of fascinating?” the Devil asks, and maybe thinking too much about the Devil is a mistake—which is great! The whole book is a trap! It’s The King in Yellow of picture books!

•25 Ned Feldman, Space Pirate (1994 children’s book)

[An alien space pirate takes Ned Feldman on a space adventure, exploring planets and encountering dangers.[

This one’s a real favorite in my household. It serves almost like a primer, a junior version of one of DMP’s longer novels. It’s all abbreviated, of course: The whole book must take place over the course of two hours or so. In that time Ned Feldman meets a conniving little crayon-munching space pirate, learns from him some of the theoretical physics (“space science”) the DMP universe runs on, travels through space, explores a planet, and returns home. It’s short and sweet.

Captain Bugbeard is one of DMP’s greatest comic creations, an egomaniacal coward who spouts strange fruit-related similes. His flag sports a motto that would get a Dada Duck (from Young Adults (#2)) fined five bucks for saying—he’s been meaning to get a better one.

This book contains one interesting little game with the inexpressibility that is at the heart of most DMP novels. Ned Feldman meets a yeti, a creature about which he says:

The yeti was the scariest thing I had ever seen. Not only was it the scariest thing I had ever seen in real life, it was also the scariest thing I had ever seen on TV or in a movie, or in an ad for a movie I was not allowed to see because it was to scary.It was also the scariest thing I had ever heard of or imagined. ¶I am not going to tell you what the yeti looked like. It was too scary.

This is good. Alan Mendelsohn (#1) had featured an “unspeakable awfulness,” an “ineffable ickiness,” but surely this indescribable yeti is more unspeakable, more ineffable that that!

Then, later, Ned concedes that they yeti “might just want to be friends.”

Note the big orange splot (#5) on Ned’s homework alongside the space battles. Like one of Mr. Plumbean’s antagonists, Ned’s teacher “believes in neatness”; this revelation should, perhaps, force us to view Ned’s piratical adventures in a new light—as a radical assertion of individuality or an external manifestation of Ned’s inner self.

•26 Adventures of a Cat-Whiskered Girl (2010 middle-grade novel illustrated by Calef Brown)

[An employee at an occult bookstore, herself a semi-feline transplant from another dimension, solves a mystery about space cats by traveling through even more dimensions.]